Bob Gibson (with glasses) enjoying a laugh with fellow Hall of Famers (l to r) Red Schoendienst, Whitey Herzog, and Lou Brock, while celebrating an anniversary of the Cardinals’ 1968 pennant winner.

Bob Gibson wanted the edge every time he took the mound. And in his absolute prime he got it, never mind that his reputation as an intimidating headhunter is more than slightly exaggerated, about which more to come. But what Henry Aaron, Dick Allen, Roberto Clemente, Al Kaline, Mickey Mantle, Willie Mays, and Carl Yastrzemski among others couldn’t do, one particularly pernicious opponent now just might.

Gibson sent his fellow living Hall of Famers a letter informing them that he’s battling pancreatic cancer. The St. Louis Post-Dispatch says Gibson visited Baltimore’s Johns Hopkins Hospital and been hospitalised in his native Omaha for two weeks, anticipating a chemotherapy program to begin Monday. Hall of Famer Jack Morris revealed Gibson’s struggle while announcing a Twins game Saturday.

It’ll keep Gibson from attending the annual Hall of Fame induction a week from today. And it has more than just the Cardinals’ considerable fan base praying for the 83-year-old former pitcher with the whip-like delivery, the sprawling follow-through, the glare from the mound before beginning his windup that made him resemble a quiet storm about to release its full fury.

Those who remember Gibson’s follow-through and finish, in which he resembled a leaning tree with his glove resembling a hanging grapefruit at one branch’s end, may wonder how on earth he could field his position. Much as they do when remembering the late Hall of Famer Jim Bunning, whose yanking sidearm delivery yanked him almost all the way to the grass on the first base side of the mound as if he’d been knocked over by an oncoming car.

Yet Gibson won Gold Gloves for his position consecutively from 1965-73. Bunning, God rest his soul, would probably have won the Concrete Glove if they’d given one.

There was an aggressive elegance to Gibson’s attack on the mound captured best by Roger Angell, in The New Yorker, in an essay called “Distance,” republished in Late Innings: A Baseball Companion in 1982:

Everything about him looked mean and loose—arms, elbows, shoulders, even his legs—as, with a quick little shrug, he launched into his delivery. When there was no one on base, he had an old fashioned full crank-up, with the right foot turning in mid-motion to slip into its slot in fromt of the mound and his long arms coming together over his head before his backward lean, which was deep enough to require him to peer over his left shoulder at his catcher while his upraised left leg crooked and kicked. The ensuing sustained forward drive was made up of a medium-sized strike of that leg and a blurrily fast, slinglike motion of the right arm, which came over at about three-quarters height and then snapped down and (with the fastball and the slider) across his left knee. It was not a long drop-down delivery like Tom Seaver’s . . . or a tight, brisk, body-opening motion like Whitey Ford’s . . . He always looked much closer to the plate at the end than any other pitcher; he made pitching seem unfair.

Angell may have been the only baseball writer to whom Gibson’s coming election to the Hall of Fame had its disturbing side: “He seemed too impatient, too large, and too restless a figure to be stilled and put away in this particular fashion; somehow, he would shrug off the speeches and honorifics when they came, just as he had busied himself unhappily on the mound when the crowd stopped the rush of the game to cheer him at Busch Stadium that afternoon in 1968. For me, at least, Bob Gibson was still burning to pitch to the next batter.”

The writer so wrongly referred to as baseball’s Homer, when in fact Homer was ancient Greece’s Roger Angell, referred to Game One of the 1968 World Series, the day Gibson broke Hall of Famer Sandy Koufax’s record for strikeouts in a World Series game. He tied Koufax when he struck out Hall of Famer Al Kaline in the top of the ninth, and his catcher Tim McCarver held onto the ball while pointing toward the center field scoreboard announcing the feat.

“Throw the goddam ball back, will you! C’mon, c’mon, let’s go!” hollered the righthander who once ordered McCarver, who’d become one of his closest friends, back to his position by barking, “Get back there behind the plate where you belong. The only thing you know about pitching is that you can’t hit it!” When Gibson finally acknowledged the roaring crowd and his achievement with an uncomfortable tip of his cap, he struck out Norm Cash and Willie Horton to end the game with a Cardinals win and seventeen punchouts.

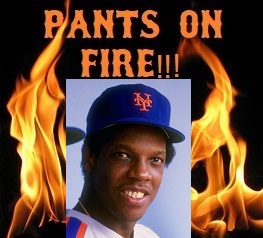

Bob Gibson striking out fellow Hall of Famer Al Kaline to tie the World Series record for single-game strikeouts that he’d break shortly after, in Game One, 1968. In that Year of the Pitcher Gibson’s regular season 1.12 ERA shone even more than Tiger pitcher Denny McLain’s 31 wins.

Watching Gibson pitch myself was like watching an assassin with the mind of Montaigne, the reflexes of a gymnast, and an arm that found the way to marry a bullwhip to a Gatling gun. The intimidating appearance and delivery sometimes masked a pitcher who applied a Warren Spahn-like intellect to his art. “Hitting is timing,” Spahn, the Hall of Fame lefthander/prankster, liked to say. “Pitching is destroying timing.” Gibson’s mind saw and raised by studying his challengers’ minds as well as their timings.

The late Hall of Famer Frank Robinson, whose plate stance Angell described memorably as “that of an impatient subway traveler leaning over the edge of the platform and peering down the tracks for the D train,” impressed Gibson as deceptive with his once-famous plate crowding, because pitchers were fooled into thinking Robinson wanted inside pitches.

Besides, they’d be afraid of hitting him and putting him on base. So they’d work him outside, and he’d hit the shit out of the ball. I always tried him inside and I got him out there—sometimes. He was like Willie Mays—if you got the ball outside to Willie at all, he’d just kill you. The same with [Hall of Famer Roberto] Clemente. I could throw him a fastball knee high on the outside corner seventeen times in a row, but if I ever got it two inches up, he’d hit it out of sight. That’s the mark of a good hitter—the tiniest mistake and he’ll punish you.

Yet this proud man, who played a major role in easing the Cardinals’ way toward complete integration earlier in his career, using his often-unheralded wit to guide white teammates out of behaviours bred into them without their even realising it, who took his own unshakeable pride in being in control on the mound and taking control of a game, could admit that he, too, had his moments when his “brains small up,” as he told Angell:

I got beat by Tommy Davis twice the same way. In one game, I’d struck him out three times on sliders away. But I saw that he’d been inching up and inching up toward that part of the plate, so I decided to fool him and come inside, and he hit a homer and beat me, one-oh. And then, in another game, I did exactly the same thing. I tried to out-think him, and he hit the inside pitch for a homer, and it was one-oh all over again. So I could get dumb, too.

Gibson’s intelligence played large in his off-field and post-baseball life. He built and opened a successful Omaha restaurant, Gibby’s, in which Angell recorded he had a direct hand in the design and construction, and for which he encouraged integrated clientele. (“A neat crowd,” Gibson once described the mixture.) He suffered no fool gladly and rejected the idea of professional sportsmen as role models. (“Why do I have to be an example for your kid?” this father of three once asked another father, gently but firmly. “You be an example for your own kid.”)

He also wittily discouraged patrons from trying to chat him about baseball when he knew they didn’t truly know the game:

You hear them say, “Oh, I was a pretty good ballplayer myself back when I was in school, but then I got this injury . . . ‘ Some cab driver gave me that one day, and I said, ‘Oh, really? That’s funny, because when I was young I really wanted to be a cab driver, only I had this little problem with my eyes, so I never made it.’ He thought I was serious. It went right over his head.

During his pitching career Gibson was uneasy with the press because he couldn’t grok their wanting “to put every athlete in the same category as every other athlete.” After his pitching days, stories began to come forth that Gibson’s sometimes forbidding public image masked a man who developed intense friendships, especially with those, black, white, otherwise, who accepted and respected that he wouldn’t say what he didn’t believe.

It was one reason why Gibson’s brief and mostly forgotten attempt at broadcasting (on ABC’s Monday Night Baseball) became as brief as it was. He’d interview a player who’d just achieved an unusual feat and question and banter with him as a fellow professional sharing professional truths about the game and its influences outside the park alike, and not a talking head.

Gibson also served actively on the board of an Omaha bank, invested in an Omaha radio station, served as a pitching coach for his friend Joe Torre in Torre’s three brief pre-Yankees managing turns, and once took the motor home the Cardinals presented him as a retirement gift to travel across the western United States.

When I was in the Air Force in the 1980s, I did my entire post-basic training/post-technical school hitch at Offutt Air Force Base in Bellevue, next to Omaha. (I worked as a member of the old Strategic Air Command as an intelligence analyst.) I knew Gibson lived in Bellevue (Angell said he was handy enough to build most of the improvements on the home including a magazine-ready patio) and I knew of his restaurant, not to mention that he was usually at the restaurant at least ten hours a day.

The temptation to go there to eat and hopefully meet him even for a few moments was equaled only by my fear that he’d see me as just another witless fan, even if I wouldn’t insult him by trying to be like the cab driver whose wannabe reverie he’d deflated so deftly.

Three months ago, I guess I did the next best thing. Challenged by an online forum participant who still buys into the myth that a home run hit off Gibson one inning was meant that batter getting a shot in or near the head his next time up, I was crazy enough to look at the game logs. Every game in which Gibson pitched. To see whether and when he really did hit anyone in the same games he surrendered home runs, and whether he’d hit a home run hitter in the same game, especially the hitter’s next time up.

Well, now. That review told me:

* Thirty-six times in his 528 major league games including 482 major league starts, Bob Gibson surrendered at least one home run and hit at least one batter in the same game.

* He only ever hit one such bombardier—Hall of Famer Duke Snider—the very next time the man batted in the game.

* He hit three such bombardiers not the next time up but in a later plate appearances in games in which they homered first.

* He surrendered home runs after hitting batters with pitches in fourteen lifetime games.

And, unless I missed something somewhere, Gibson’s most frequent plunk victim was Roy McMillan, a shortstop for the Braves (when he first took a Gibson driller) and the Mets, who was a study defensively but about as much of a hitter as Wilt Chamberlain was a baseball player. Gibson hit McMillan five times lifetime; McMillan could have been forgiven if the mere mention of Gibson’s name inspired lustful thoughts of first degree murder.

The fifth time was 20 August 1965, against the Mets in New York. McMillan took one in the bottom of the third. With two out in the top of the fifth Mets starter Al Jackson hit Gibson with a pitch. (The plunk hurt the Mets more than Gibson as it turned out: the Cardinals scored from there on a single, a double steal, an RBI triple, an RBI single, and another RBI triple.) McMillan must have wanted to offer to have Jackson’s children right then and there.

Right now about the only thing anybody wants to offer Bob Gibson is every prayer they can think of. He’s up against an enemy that won’t respond easily to a brushback, a knockdown, a plunk, or an elegantly violent strikeout.

I wish now that I’d taken the chance to meet him back in my Omaha days. I probably would have liked and respected him. Even more than I’d liked and respected him when he pitched. All I can do now is join those praying for him.