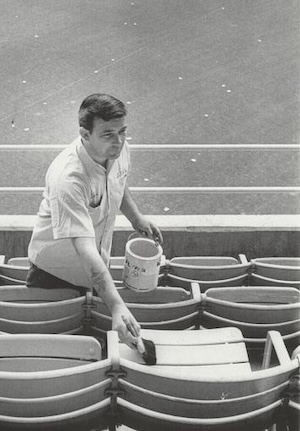

Olaf Hall, RFK Stadium worker, painting white an outfield seat struck by one of Senators legend Frank Howard’s mammoth home runs.

Time was when I worked shy of a year at a Washington, D.C. think tank, lived just outside Washington in Capitol Heights (Maryland), and walked the five miles to work every day on behalf of saving what little money I earned. The route from my little hideaway to my job included walking past RFK Stadium.

Perhaps providentially, I had no choice but to walk past the old tub. Not unless I wanted to take the Metrorail, which had a station that was a short walk from my little hideaway. But the baseball maven in me would have had me flogged for even thinking about avoiding RFK.

My days began, after all, with spending time and my breakfast with Shirley Povich, the founding father of the Washington Post‘s sports section. He founded it more or less when the ancient Washington Senators (as in, Washington–First in war, first in peace, and last in the American League) won their only World Series in (count ’em) two tries before they absconded to Minneapolis.

When those days didn’t begin with Povich, they began with Thomas Boswell, now the freshly-inducted Hall of Fame baseball writer, also of the Post. (I refuse to say the official award name until the Baseball Writers Association of America gives it a name far more properly fitting than “Career Excellence Award.” Like maybe the Shirley Povich, Roger Angell, or Wendell Smith Award.)

I’d then tuck the paper into my briefcase and make the aforesaid five-mile walk. Passing RFK Stadium. With only one apology, that I’d never gotten to see a baseball game there and that I’d forgotten to buy myself a Washington Senators hat while I worked in and lived next to D.C. And while I tended to walk with a certain vigour, on behalf of losing physical weight and as much mental and spiritual baggage as I could lose (I was separated from my first wife and en route a divorce), I didn’t mind slowing down to take a slow stroll around the Washington Hall of Stars—if I could talk an early-arriving stadium staffer into letting me in.

Howard only looked as though he was going send a pitcher’s head and not a baseball into the seats. No gentler giant ever played baseball in RFK Stadium—or anywhere.

Up in the mezzanine were Hall of Stars Panels 6 through 8. Honouring such Old Nats as owner Clark Griffith, Hall of Famers Joe Cronin, Goose Goslin, Bucky Harris, Walter Johnson, Harmon Killebrew, and Early Wynn. Honouring such Negro Leagues legends as Hall of Famers Josh Gibson and Buck Leonard. Honouring such not-quite-Hall of Fame Old Nats as Ossie Bluege, George Case, Joe Judge, Roy Sievers, Cecil Travis, Mickey Vernon, and Eddie (The Walking Man) Yost. Honouring Vernon’s fellow Second manager Gil Hodges. Honouring such Second Nats as Chuck Hinton and Frank Howard.

It was easy to take in such history and all its pleasantries and calamities alike. It was tough to look at the field below and see, aside from the football markings for the Redskins (oops! today we call them the Commanders), the inevitable ghosts of the saddest day in RFK Stadium history: the day heartsick fans broke the joint over the hijacking of the Second Nats to Texas.

“Right where . . . the Senators played their final game in 1971 and the Nationals brought baseball back in 2005—that’s where the crews from Smoot Construction are separating concrete from metal so they can be hauled away separately,” writes the Post‘s Barry Svrluga. “Whatever can be repurposed will be . . . ”

Anyone who has driven or walked by RFK Stadium over the past decade or so knew it would come down, knew it had to come down eventually. Long ago it devolved into an ugly relic that served no one. This was inevitable.

But I have to admit that as I watched the process over that morning last week, I got a little emotional . . . I was at that first game when baseball came back. I saw the stands along the third-base line bounce. I watched Ryan Zimmerman drill his first walk-off home run to beat the New York Yankees on Father’s Day in 2006. I watched Nationals owner Ted Lerner and then-manager Manny Acta dig out home plate from the ground after the final game in 2007.

. . . Do yourself a favor, though. Take some time over the coming weeks and months to drive west on East Capitol Street from Interstate 295 or east on Independence Avenue from downtown. Do a loop around RFK before it vanishes completely. This is athletic history. It’s D.C. history. And piece by piece, it’s finally being torn down.

Ryan Zimmerman mobbed and hoisted after his Father’s Day game-winner in RFK, 2006.

Well, I took my slow strolling loops around the joint 35 years ago. When baseball’s return to the nation’s capital was still a fantasy. “Pardon my French: le baseball est revene á Washington,” wrote Radio America founder James C. Roberts, in Hardball on the Hill, in 2001. “In Montreal, that’s how they would say, ‘Baseball is back in Washington.’ They are words I long to hear—in any language.”

Baseball might appear now and then in the old tub until 2005, never more transcendantally than when they cooked up the Cracker Jack Old-Timers Game in 1982 . . . and Hall of Fame shortstop Luke Appling, leading off for the American League’s alumni at age 75, caught hold of a second-pitch meatball from Hall of Famer Warren Spahn, age 61, and sent it behind the specially-shortened left field fence, but traveling a likely 320 feet—a major league home run no matter how you slashed it.

“It was a good pitch, it was right there, and I just swung away,” Old Aches and Pains deadpanned after the game.

Machinations of dubious ethics to one side, including baseball government taking temporary ownership, Montreal (her city fathers, not her baseball fans) then didn’t seem to want its Expos that much anymore. Washington was only too happy to welcome them. Even the President of the United States donned a team jacket of the newly-rechristened Nationals and threw a ceremonial first pitch. Actual major league pitchers would kill puppies to have the kind of slider Mr. Bush threw—with a ball bearing a unique if sad survival story.

Senators relief pitcher Joe Grzenda had only to rid himself of Yankee second baseman Horace Clarke to secure a Second Nats win on that heartsickening farewell day in 1971. Grzenda never got the chance because all hell that spent much of the game threatening finally broke loose. Fans poured onto the field in a perfect if grotesque impersonation of hot lava soaring over and down a volcano’s side. The umpires forfeited the game to the Yankees. When the mayhem ended, RFK Stadium resembled the net result of a bombing raid.

Perhaps miraculously, Grzenda saved the ball. He presented it to Mr. Bush on Opening Day 2005. It took about 12,000+ days for that ball to travel from the RFK mound to the RFK plate by way of its detour in Grzenda’s custody.

The old structure, built as D.C. Stadium to open in 1962, renamed for an assassinated presidential candidate in 1969, has been the site of assorted joys and jolts. It closed officially in 2019; its final official baseball game was in 2007. “Without RFK, who knows where we would be?” said Chad Cordero, relief pitcher, and the first man to hold the official closer’s job as a Nat, upon that closing. “We might still be in Montreal. We could be somewhere else. This place has treated us well. We have some great memories here.”

And, despite the circumstances that brought me there, so do I. Even if they have to be one part a Hall of Stars display and 99 parts my imaginings.

Most of those stars didn’t play in RFK Stadium, but it was quiet fun to think about Early Wynn, traded away long before, but showing up for the White Sox trying to keep Chuck Hinton from hitting one out. (On the 1962 Second Nats, Hinton tied for the team home run lead with . . . Harry Bright, the man who’d be remembered best, if at all, as the strikeout victim securing Hall of Famer Sandy Koufax’s breaking of the single-game World Series strikeout record a year later.)

It was even more fun remembering the occasional Senators game televised to New York on a Game of the Week offering and watching gentle giant Frank Howard carve his initials into some poor pitcher’s head as he hit one into orbit. Howard, the Senator above all the rest who didn’t quite enjoy the team being hijacked to Texas. Howard, who brought that heartsick RFK crowd to its feet when he hit one into the left field bullpen midway through the game to start the Second Nats comeback that turned into a win that turned into a forfeit.

“What can a guy do to top this?” he asked after it was all over. “A guy like me has maybe five big thrills in his lifetime. Well, this was my biggest tonight. I’ll take it to the grave with me. This was Utopia. I can’t do anything else like it. It’s all downhill the rest of the way.” That from the man who also once said, “The trouble with baseball is that, by the time you learn to play it properly, you can’t play anymore.”

They’re demolishing RFK Stadium slowly, on behalf of environmental concerns, so the Post says. The seats are long gone. The rest has been going one portion at a time. It wasn’t the most handsome of the old (and mostly discredited) cookie-cutter stadiums. But something seems as off about the piecemeal disassembly as the big dent in the rooftop that made the joint resemble a stock pot left on the stove too long.

Note: This essay was published originally by Sports Central.