Davey Johnson at a 2016 reunion of his 1986 Mets. L to R: Keith Hernandez (1B), Jesse Orosco (RP), Ray Knight (3B), Lee Mazzilli (OF-PH), Johnson. They made the Deltas of Animal House resemble monks.

In 2012, on the threshold of managing the Nationals to their first National League East title after they moved from Montreal, Davey Johnson had mortality very much on his mind, after his one-time Mets player and lifelong friend Gary Carter lost a battle with brain cancer.

Johnson had seen Carter the previous winter and played golf with him at Carter’s charity event for needy children. When The Kid died, Johnson couldn’t bring himself to attend the funeral. “He would want me to be doing what I loved and not crying over him,” Washington Post writer Adam Kilgore remembers Johnson saying. “I don’t want nobody crying over me, either. It’s that simple. It may be callous, but I don’t look at it that way.”

The man who bookended both Mets World Series championships—he flied out to Cleon Jones to finish the 1969 Miracle Mets triumph, and managed the (shall we say) swashbuckling 1986 Mets to a World Series title—died Friday at 82.

Perhaps former Nats general manager Mike Rizzo described him best, in a Saturday text message to Kilgore: “Davey was a tough guy with a caring heart. One of the great baseball minds of all-time. A forward thinker with an old-school soul.”

During his playing days, Johnson took computer courses as a Johns Hopkins University graduate student and used what he learned to develop best possible baseball lineups. Offering one to his irascible manager Earl Weaver, who spurned it, Johnson said, “I don’t know whether to tell Earl, but the sixth-worst lineup was the one we used most of the time [in 1968].”

When he became a manager in the Mets’ system and then for the Mets themselves, Johnson brought such thinking plus his computer into his clubhouse and dugout. It’s entirely likely that he pushed the door open to sabermetrics as an active game tool and not just a postmortem analysis. He looked for the matchups and took the concurrent measure of his players at once.

But he wouldn’t let you call him one of the smartest of the game’s Smart Guys. “I never thought I was smart,” he said in 2017. “But I love to figure out problems. Through my stubbornness and relentlessness, I get to the end.” Bless him, he had to learn the hard way that the end had more than the meaning he had in mind.

“I treated my players like men,” he once said of his Mets, whom he led out of a dark age through a pair of hard pennant races and second-place finishes before they went the 1986 distance. “As long as they won for me on the field, I didn’t give a flying [fornicate] what they did otherwise.”

Not even when they celebrated a too-hard-won 1986 National League Championship Series by trashing their United Airlines charter DC-10 with partying that made the Gas House Gang and Animal House’s Deltas resemble conclaves of monks.

Maybe Johnson really was a forward thinker with an old-school heart. He treated like men a team with too many players behaving off the field as though their second adolescence came or their first hadn’t ended yet. Such straighter arrows as Hall of Fame catcher Carter plus infielders Howard Johnson, Ray Knight, and Tim Teufel, and outfielder Mookie Wilson, were the exceptions.

“He was just a player’s manager,” said Wilson upon Johnson’s passing. “He made it fun to go to the field. He laid down the law when needed, but other times he just let us play.” Then, and right to the end of his tenure on the Nationals’s bridge, Johnson liked to tell his players, “You win games. I lose them.”

Little by little, general manager Frank Cashen got less enchanted with his team and his laissez-faire manager. No two more opposite minds could ever have come through the Oriole system to bring the Mets to the Promised Land. And almost as swiftly as they got there, Cashen began letting his most characteristic players escape.

“Maybe we’ve made too many trades for guys who are used to getting their asses kicked,” said Dwight Gooden, the pitching star first made human by ill-advised work to fix what wasn’t broken in spring training 1986 and then a long war with substance abuse, to Jeff Pearlman for The Bad Guys Won. The guys who used to snap . . . they’re gone.”

Some also thought Cashen’s gradual dismantling of the team that should have ruled the earth or at least the National League for the rest of the decade took a toll on and the edge off Johnson’s once-formidable in-game cleverness. (He was known to be less than enthusiastic about several trades instigated by either Cashen or his then right-hand man Joe McIlvane.)

Once a second base star with the Orioles who also set a record for home runs in a season by a second baseman as a Brave, Johnson faced the proverbial firing squad in early 1990. It wouldn’t be the last time he brought a team to the Promised Land or its threshold only to be shoved to one side.

He took the Reds to the first-ever National League Central title after the post-1994 strike realignment—despite being told early that season it would be his last on that bridge. Capricious owner Marge Schott apparently didn’t like that he’d lived with his wife before she became his wife.

Then the Orioles made a dream come true and hired Johnson to manage them. Season one: 1996 American League wild card. Season two: The 1997 AL East. Neither brought him a World Series title. The wild card led to an American League Championship Series loss. (The outstanding memory: Jeffrey Maier making sure Derek Jeter’s long drive wouldn’t be caught for a homer-robbing out.) The division title led to another ALCS loss (to the Indians).

Johnson and Orioles owner Peter Angelos weren’t exactly soul mates. Angelos steamed all 1997 when Johnson fined Hall of Fame second baseman Roberto Alomar for missing a team function and ordered the fine to be paid to the charity for which Mrs. Johnson worked as a fundraiser. Johnson admitted soon enough that that was a mistake. (Alomar paid the fine to another charity.) Angelos wanted Johnson to say publicly he’d been “reckless.”

The manager declined, politely but firmly. Then, after the Orioles postseason ended, Johnson waited for Angelos to tell him, ok, you won the division again, that’s enough to let bygones be bygones. “Last week, Johnson called the Oriole owner,” wrote the Washington Post‘s Thomas Boswell, on 6 November 1997.

They talked. And yelled at each other some, too. Aired their differences. Johnson hoped it would help. That’s how it works in the clubhouse. You got a problem with me? Spit it out. Then work it out.

Johnson took a chance on Angelos. When challenged, maybe he’d respond like a big leaguer. Sometimes, after the venting is finished, a friendship develops—even a strong one. Sometimes you just agree to disagree and keep on fussing, like Earl Weaver and Jim Palmer. Either way, you respect each other and pull in the same direction.

Instead, all Johnson heard from Baltimore was silence. So, Johnson had his answer. Angelos wanted Johnson to resign as manager. If the Orioles fired him, they’d have to pay Johnson $750,000 next season . . .

. . . Nobody wants to be where they are not wanted. Especially if they are wanted almost everywhere else. “I’ll make it easy for him,” Johnson said. He wrote to Angelos: “I offer my resignation.”

On the same day Johnson was named American League manager of the year by the baseball writers, his resignation was accepted by Angelos.

Taking the high road helped make sure Angelos wouldn’t try to renege on the $750,000 he still owed Johnson for 1998. You think Angelos appreciated that high road? Not a chance. As with departed Orioles broadcast mainstay Jon Miller, Johnson “asked to be treated with the respect—in contractual terms—that his performance merited.”

In response, Angelos orchestrated the exodus of each. After Miller left, Angelos claimed Miller wanted to leave, contrary to appearances and Miller’s amazed protestations. Yesterday, Angelos said of Johnson, “It seems to me he wanted to move on.” By way of comment, let it be noted that Angelos has one of the rare law firms in which there are no partners. It’s just his name on the door.

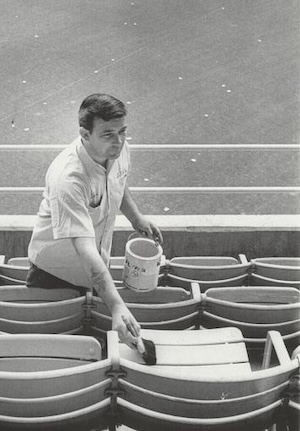

Once a star second baseman in Baltimore, Johnson presses a point as a successful Orioles manager—who ran afoul of owner Peter Angelos, as Angelos made sure only too many did.

Johnson didn’t remain unemployed for long. (Neither, of course, did Jon Miller.) The Dodgers brought him to the bridge for 1999. He had his first losing season as a manager (though he won his 1,000th game in the job), then turned the Dodgers around in 2000 but fell short of the division title. Back to the firing squad. Again.

He then managed American and (one year) Netherlands teams in international competition before being hired into the Nationals front office. When manager Jim Riggleman decided to quit in June 2011, Johnson was named his eventual successor. He took them to a third-place NL East finish, their best since moving to Washington from Montreal, then led them to the NL East title in 2012 but a division series loss to the defending world champion Cardinals.

That didn’t keep his players from respecting him. Johnson must have come a very long way from the years when a laissez-faire approach to managing men eventually blew up in his face. I could be wrong, but I don’t remember any of his Cincinnati, Baltimore, Los Angeles, or Washington teams accused of trashing jumbo jets, for openers.

“If you come out here and you play hard and really work your tail off,” said his Rookie of the Year winner Bryce Harper during that season, “he’s going to like that. He plays it hard and he plays it right. That’s the type of manager you want.”

“Davey was an unbelievable baseball man but an ever better person,” said longtime Nats mainstay Ryan Zimmerman in a text to Kilgore. “I learned so much from him about how to carry myself on and off the field. No chance my career would have been the same without his guidance. He will be deeply missed by so many.”

On and off the field. Make note.

Johnson did win his second Manager of the Year award guiding the 2012 Nats. He’s one of seven to win it in each league; his distinguished company: Tony La Russa, Lou Piniella, Buck Showalter, Jim Leyland, Bob Melvin, and Joe Maddon. After a second-place 2013—made slightly worse than it looked when he opened the season saying it looked like a World Series-or-bust year to be—Johnson elected to retire.

“In one respect,” Boswell wrote after his Oriole departure, “he’s different than almost every other manager of his generation. He doesn’t come to ownership with hat in hand. He doesn’t act like he’s lucky to be a big league manager and could never get any other job half so grand. He’s an educated, broadly accomplished man. And he carries himself that way. It has cost him.”

Johnson learned compromise as he aged, both in the game and away from it. So did a few of his former players who once butted heads with him or otherwise made him resemble Emperor Nero fiddling while Flushing flushed. (Darryl Strawberry, with whom Johnson had a relationship often described as “testy,” came to believe Johnson was the greatest manager he ever played for.)

Maybe tragedy had something to do with it, too. Johnson’s daughter, Andrea, once a nationally-ranked surfer but a diagnosed schizophrenic, died of septic shock in 2005; his stepson, Jake, died of pneumonia in 2011. (He also has a stepdaughter, Ellie.) Even the most impregnable man can be wounded. Even men who win two World Series as an Orioles second baseman and one managing the wildest and craziest Mets team of the 1980s.

May the forward-looking old-schooler be escorted to a happy reunion with his daughter, stepson, host of teammates, and Kid Carter in the Elysian Fields.