Dave Stenhouse, the first first-year pitcher to start an All-Star Game . . . but pensionless thanks to the 1980 pension realignment’s freezout of short-career major leaguers who played prior to 1980. Stenhouse and several more of his fellow frozen-out players died in 2023.

Commissioner Pepperwinkle wasn’t baseball’s only leader to drop a ball or three in 2023. The Major League Baseball Players Association has welcomed minor leaguers into its ranks and backed them on a five-year contract doubling minor league player salaries . . . but still offered not even a peep about pre-1980 short-career major leaguers frozen out of the 1980 pension plan realignment.

That re-alignment began pensions to major leaguers with 43 verified days on major league rosters and health benefits to those with one verified such day. But it went to those whose careers ended after 1980. Those with those verified days before 1980? Nothing.

The union line then was that most of those pre-1980 short-career players were mere September callups. Not so fast. The majority of those players saw major league time in any year of their careers prior to September, as early as April, or even by way of making major league rosters out of spring training.

A few more of those frozen-out players passed to the Elysian Fields this year, including:

Mike Baxes (92; Kansas City Athletics, 1956, 1958)—A product of the legendary San Francisco Seals (Pacific Coast League), military service disrupted Baxes’s career in the 1950s before the Seals, suddenly cash strapped, sold Baxes and three other players to the Kansas City Athletics for $50,000. The infielder moved from backing third base to backing up shortstop and got his first major league hit off ill-fated Indians pitcher Herb Score in 1956.

Back to the minors, Baxes earned a rep as a slick fielding shortstop with a good bat. (He hit two grand slams in a 1957 game for the Buffalo Bisons, which the Bisons won 20-1; he was even named the International League’s Most Valuable Player.) He returned to the A’s in 1958, and became their starting second baseman, but an ankle sprain turning a double play helped ruin what remained of his career. He returned to the PCL but called it a career in 1961.

Rob Belloir (75; Atlanta, 1975-78)—The 25th major league player to have been born in Germany. (His father was a military officer stationed in Heidelberg.) Started his short Show life hitting like a Hall of Famer with a 4-for-8 spell between two games including four runs batted in in the first of the game. He couldn’t sustain it and spent the next three seasons up and down between the Braves and their Richmond (VA) AAA affiliate.

A member of Mercer University’s Hall of Fame (he lettered in both baseball and basketball), Belloir became a church minister after his playing days.

Bill Davis (80; Cleveland, 1965-66; San Diego, 1969)—Among his claims to fame, the first baseman appeared on five Topps rookie cards, pairing him with one or two other players, without ever landing a card of his own: four times as an Indian (for whom he went 3-for-10 in 1965 including a double), and once as a Padre. He shared his Padres rookie card with outfielder—and eventual back-to-back World Series-winning manager—Clarence (Cito) Gaston.

John Glenn (93; St. Louis, 1960—No relation to the astronaut, this center fielder was a 1950 Brooklyn Dodgers signing blocked by Hall of Famer Duke Snider before he was traded to the Cardinals for outfielder Duke Carmel and pitcher Jim Donohue. He played fifteen years in the minors and might have reached the Show in 1958 but for knee surgery. As a Cardinal, he played in 32 games and switched to left field. He left baseball in 1963 to work in the chemical industry before his retirement. “Baseball,” he once said, “made it possible for me to know what life was all about and to live with people of different cultures.”

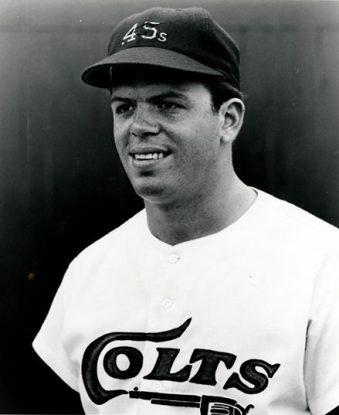

Dave Stenhouse (90; Washington, 1962-64)—The first first-year pitcher to start an All-Star Game, Stenhouse’s feat came during his only truly healthy major league season. A long minor league career preceded his rookie season (at age 28); his All-Star turn included striking out Hall of Famer Roberto Clemente.

A knee injury turned his 1962 from plus to minus, unfortunately; Stenhouse would also deal with bone chip surgery on his pitching elbow before his brief major league career ended. But his happy second act following a few more minor league seasons was spent in his native Rhode Island, as the longtime pitching coach for Rhode Island College and, later, Brown University. (He was also the father of former Montreal Expos outfielder Mike Stenhouse.)

Those men, too, died without seeing a full major league pension. Their only redress since the 1980 realignment was a deal between then-commissioner Bud Selig and then-Players Association leader Michael Weiner: $625 per quarter for every 43 days’ worth of MLB time, up to four years’ worth, with the stipend hiked fifteen percent in the 2022-23 lockout settlement. The kicker: when they, too, passed to the Elysian Fields, neither they nor their fellow neglected could pass that stipend on to their families.

Barely 500 such pre-1980 short-career major leaguers still live on earth. They still despair of getting more press attention for the wrong done them in 1980. They mourn when more among their ranks depart to the Elysian Fields. They long for the day yet when baseball will acknowledge and do right by them at last.

They still cling to hope that somehow, some way, someone with true influence will remember what they swear was longtime union leader Marvin Miller’s hope that the issue would be revisited and redressed fully after his tenure ended.

I’ve had the pleasure of interviewing and befriending a few of those players. They’re not bomb-dropping radicals. They’re not about to storm the ballparks. They ask for nothing more, but nothing less, than what they should have had if not for the short sight of their own union and the owners of the time who agreed to the realignment freezeout.

Miller himself once believed a key reason for the original freezeout was that the monies simply weren’t there to take care of those players. But that was 1980. The union’s 2022 revenues were a reported $82 million before expenses, $55 million after them. The players’ welfare and benefits fund is believed to be $3.5 billion.

Doing right by the remaining 500+ pre-1980 short-career major leaguers? Forget breaking the bank. It probably wouldn’t put more than a pinhole-sized dent in a wall.