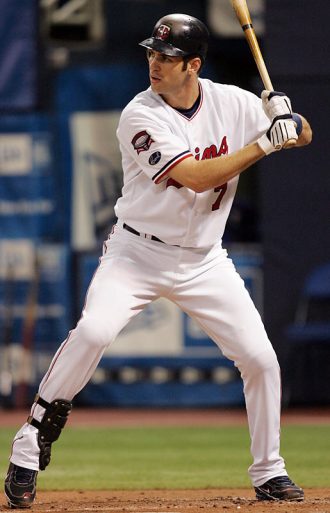

L to R: Newly-elected Hall of Famers Beltré, Helton, Mauer—They’ll join Contemporary Baseball Era Committee choice and longtime manager Jim Leyland on the Cooperstown stage come July.

The third baseman whose surname begins with “belt” and was way more than just a great belter. The first baseman who wasn’t just a Coors Canaveral product at the plate. The catcher forced to first base by concussion but who forged his case as the game’s number seven catcher all-time, defying his haters who still call him a thief.

Ladies and gentlemen, meet your newest Hall of Famers—Adrián Beltré, Todd Helton, and Joe Mauer. Beltré and Mauer deserved to be the first-ballot Hall of Famers they are now. Helton should have been, too, if only the voters his first time around on the Baseball Writers Association of America ballot had taken the dive that went deeper and deeper the longer Helton stayed on the ballot.

Beltré is probably in the most unique position of the trio. The number four third baseman of all (I’d rank him a touch higher for his combination of power hitting and off-the-charts defense) has something none of his peers can claim. Quick: name the only third baseman, ever, with 1) 3,000+ hits and 2) five or more Gold Gloves.

Hall of Famer Wade Boggs has two Gloves. Hall of Famer George Brett has one. Hall of Famer Paul Molitor (who probably got in more as a designated hitter than a third baseman) has none. Beltré, of course, has five. Now you can argue that a lot of Gold Glove award voting has been suspect over the years. You can’t argue with only two of the quartet being in the top twelve for run prevention at third base: Beltre (+168 total zone runs; 2nd) and Boggs (+95; 12th).

There’s only one other third baseman in the top twelve for run prevention who had anything like Beltré’s power in hand with it: Hall of Famer Mike Schmidt. Hall of Famer Eddie Mathews (512 home runs) was worth 40 defensive runs saved but that doesn’t get him quite to the levels of Beltré and Schmidt among the biggest bopping third basemen.

Here’s Beltré, among post-World War II/post-integration/night-ball era Hall of Fame third basemen, according to my Real Batting Average metric (RBA): total bases + walks + intentional walks + sacrifice flies + hit by pitches, divided by total plate appearances:

| HOF 3B | PA | TB | BB | IBB | SF | HBP | RBA |

| Mike Schmidt | 10062 | 4404 | 1507 | 201 | 108 | 79 | .626 |

| Chipper Jones | 10614 | 4755 | 1512 | 177 | 97 | 18 | .618 |

| Eddie Mathews | 10100 | 4349 | 1444 | 142 | 58 | 26 | .596 |

| Scott Rolen | 8518 | 3628 | 899 | 57 | 93 | 127 | .564 |

| George Brett | 11625 | 5044 | 1096 | 229 | 120 | 33 | .561 |

| Ron Santo | 9397 | 3779 | 1108 | 94 | 94 | 38 | .544 |

| Wade Boggs | 10740 | 4064 | 1412 | 180 | 96 | 23 | .538 |

| Adrián Beltré | 12130 | 5309 | 848 | 112 | 103 | 97 | .533 |

| Paul Molitor | 12167 | 4854 | 1094 | 100 | 109 | 47 | .510 |

| Brooks Robinson | 11782 | 4270 | 860 | 120 | 114 | 53 | .458 |

| HOF AVG | .555 | ||||||

You see he was hurt most at the plate by taking a lot less unintentional walks than everyone else on the list. But he’s the number two most run-preventive third baseman ever behind Brooks Robinson. His combination of power and defense should nudge him up to the number three all-around third baseman who ever played. WARriors, take note: Beltré’s 93.5 is bested among Hall third basemen by two, in ascending order: Mathews (96.0) and Schmidt (106.8).

Among his group of Hall of Famers, Beltré was also the most fun Fun Guy of the game. Even if his career was an ascending trajectory to genuine greatness (people still wonder how the Dodgers could have let him take a hike into free agency), there was always a sense about him that he really did play more for the fun of it than the riches of it.

I’ve asked elsewhere: how often do you get to send one of the real Fun Guys to Cooperstown? Too many playing or managing greats were about as fun as open-heart surgery. Too many of the game’s Fun Guys weren’t all that much fun when they were actually on the field or at the plate. (Dick Stuart, for example, was one of the funnest of his time’s Fun Guys—but he earned his nickname Dr. Strangeglove at first base. He only got to play major league baseball because he could hit baseballs across city limits.)

Ernie Banks, Yogi Berra, Bert Blyleven, Roy Campanella, Dizzy Dean, Whitey Ford, Lefty Gomez, Rickey Henderson, Minnie Miñoso, David Ortíz, Satchel Paige, Babe Ruth, and Warren Spahn were bona-fide Hall of Famers and Fun Guys in the bargain as players. (And several of them had to do it through unconscionable bigotry.) Casey Stengel was both as a manager. Beltré will grace their company.

I did notice someone aboard social media ask aloud if someone could arrange for his old Texas teammate Elvis Andrus to come rub his head at his induction. Not a half bad idea. Barring that, maybe the Hall could arrange for Beltré head-touching bobbleheads to pass out come induction day? Barring that, maybe the Hall staff would let him drag the on-deck circle mat lonce more?

Helton may have finished what Hall of Famer Larry Walker started and fractured the idea that a career spent half or more with Coors Field as your home ballpark will kill or at least cast abundant doubt on your Hall credentials. Helton lacked what Walker had, enough time in another uniform to show that he was Hall of Fame good without the Coors factor. But Helton has this distinction: the first Rockie-for-life to go to Cooperstown.

Now, look deeper, once again, please. The Toddfather posted an .855 OPS on the road to his 1.048 at home. An .855 OPS across the board might mean a spot in the Hall of Fame for a lot of players. Helton’s road OPS is higher than the across-the-board OPSes of (in ascending order) live ball-era Hall of Famers Eddie Murray, Gil Hodges (who played most of his career in a bandbox home park), Orlando Cepeda, Ben Taylor (Negro Leagues), Sunny Jim Bottomley, Harmon Killebrew; and, one point below Fred McGriff. His across-the-board .953 is better than all but nine Hall of Fame first basemen.

Let me apply my RBA to Helton among post-World War II/post-integration/night-ball era Hall of Fame first basemen:

| First Base | PA | TB | BB | IBB | SF | HBP | RBA |

| Jim Thome | 10313 | 4667 | 1747 | 173 | 74 | 69 | .653 |

| Jeff Bagwell | 9431 | 4213 | 1401 | 155 | 102 | 128 | .636 |

| Todd Helton | 9453 | 4292 | 1335 | 185 | 93 | 57 | .631 |

| Willie McCovey | 9692 | 4219 | 1345 | 260 | 70 | 69 | .615 |

| Harmon Killebrew | 9833 | 4143 | 1559 | 160 | 77 | 48 | .609 |

| Fred McGriff | 10174 | 4458 | 1305 | 171 | 71 | 39 | .594 |

| Gil Hodges | 8104 | 3422 | 943 | 109 | 82 | 25 | .565 |

| Orlando Cepeda | 8698 | 3959 | 588 | 154 | 74 | 102 | .561 |

| Eddie Murray | 12817 | 5397 | 1333 | 222 | 128 | 18 | .554 |

| Tony Pérez | 10861 | 4532 | 925 | 150 | 106 | 43 | .526 |

| HOF AVG | .594 | ||||||

Helton has the number three RBA among those Hall of Fame first basemen, he’s 37 points above the average RBA for those Hall first basemen, and it wasn’t all or purely a product of Coors Field. He also had a 144 OPS+ over his ten-year peak of 1997-2007. OPS+, of course, adjusts for ballpark factors. That peak OPS+ alone should disabuse you once and for all about whether the Toddfather was pure Coors.

By the way, for those of you obsessed with swinging strikeouts at the plate and the metastasis thereof, be reminded that Helton lifetime walked more than he struck out, especially as the leverage situation rose. He averaged eleven more walks (96) than strikeouts (85) per 162 games, and he walked 160 times more than he struck out. Would you like to know how many of the other aforelisted Hall of Fame first basemen walked more than they fanned? Z-e-r-o.

Mauer joins a unique Cooperstown group—one of the three field positions (catcher) that have resulted in only three first-ballot Hall of Famers. (It’s still impossible to believe that Yogi Berra wasn’t a first-ballot Hall of Famer.) Thus does Mauer join Johnny Bench and Ivan Rodríguez in the Cooperstown Trinity of the Tools of Ignorance. (The other two positions with only three first-time Hall of Famers: first base and second base.)

He also has a .569 RBA that puts him third among post-World War II/post-integration/night-ball Hall catchers. (Only Mike Piazza and Roy Campanella—who played in the same bandbox as Hodges when he made the Show in 1948—are ahead of him.) He wasn’t all bat as a backstop despite his gaudy batting averages, either; the pitchers who threw to Mauer posted an ERA almost a full run below his league average, he was worth +65 total zone runs behind the dish, and he threw out a respectable 33 percent of runners who tried to steal on him lifetime. (He led the American League twice: 53 percent in 2007; 43 percent in 2013.)

WARriors should remind themselves, too, that in the ten seasons Mauer played as the Twins’ regular catcher, he out-WARred the three other catchers active during all ten of those seasons by a wide margin: his 44.6 bested Victor Martinez (28.1), Yadier Molina (27.6), and Jorge Posada (20.0).

Well, now. A year ago, after Scott Rolen’s election to the Hall of Fame provoked the usual chatter about who’d be elected this year, Twins fans tried to smother social media with assaults and batteries of Mauer for “stealing” the money in that yummy contract extension he signed before his first concussion compelled the Twins to get him the hell out from behind the plate.

He suffered his second well into the extension, chasing a foul ball from first base. Those brain-dead fans either forgot, never knew, or didn’t care that injuries incurred in the line of duty don’t equal goldbricking or defrauding. I swore then that I wouldn’t say another word about their idiocies, but I can’t resist today.

Who has the last laugh now?