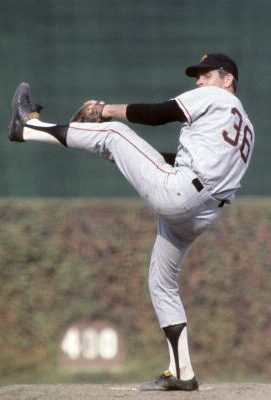

Bob Gibson, whose talismanic 1.12 ERA may remain the best-remembered element of 1968’s Year of the Pitcher. But . . .

When Hall of Fame pitcher Bob Gibson lost his battle with pancreatic cancer at 84 last Friday night, two things above all seemed looming large over any retrospective of the St. Louis Cardinals marksman who was just as good a man as a pitcher. Even above his striking overall World Series performance record.

Thing One: Gibson’s still somewhat exaggerated image as an intimidator. So much so that a friend hailed me aboard a social media platform to remember Gibson saying he’d knock his own grandmother down if she dared to challenge him. It took me a short while to convince him Gibson never said that about his grandmother or any other relative.

For the record, Hall of Famer Henry Aaron plagiarised Hall of Fame pitcher Early Wynn to say Gibson would knock his grandma down, and Aaron mis-plagiarised Wynn about the challenge part. Wynn had actually said he’d knock Grandma down if she dug in against him. Apple sauce and orange chicken.

The closest Gibson ever came to admitting he insisted upon going one-up on family members is when he admitted, a little puckishly, when asked if competitiveness was his more-or-less lifelong companion, “I guess you could say so. I’ve played a couple of hundred games of tic-tac-toe with my little daughter, and she hasn’t beaten me yet. I’ve always had to win. I’ve got to win.”

Which leads to Thing Two, since Gibson revealed his tic-tac-toe conquering during the same year’s World Series: 1.12. That was Gibson’s earned run average in 1968. A number at least as talismanic for baseball fans ancient and modern as have been numbers such as 60, 61, 511, 714, 755, 2,130, and 5,714.

To this day you can meet people who think 1.12 was the reason, maybe the only reason, or the reason first above lesser challengers, why the Year of the Pitcher freaked the Show’s government enough to deliver a couple of rules changes after 1968 that were just as significant as the change that made the damn season almost necessary in the first place.

Hall of Fame writer Roger Angell, who admires and loves top-of-the-line pitching as deeply as he does top-of-the-line hitting and defense, observed in an October 1968 essay (“A Little Noise at Twilight“) that, by mid-July 1968, “it was plain to even the most inattentive or optimistic fans that something had gone wrong with their game.”

Why were the pitchers so good? Where were the .320 hitters? What had happened to the high-scoring slugfest, the late rally, the bases-clearing double? The answers to these questions are difficult and speculative, but some attempt must be made at them before we proceed to the releasing but somewhat irrelevant pleasures of the World Series. To begin with: Yes, the pitchers are better—or, rather, pitching is better. All the technical and strategic innovation of recent years have helped the defenses of baseball; none have favoured the batter. Bigger ballparks with bigger outfields, the infielders’ enormous crab-claw gloves, more night games, the mastery of the relatively new slider pitch, the persistence of the relatively illegal spitter, and the instantaneous managerial finger-wag to the bullpen at the first hint of an enemy rally have all tipped the balance of this delicately balanced game.

Gibson didn’t need the Year of the Pitcher to prove his greatness or make himself a Hall of Famer. He’d established that in a gradual buildup from his first major league gigs in 1959 forward, including and especially during two previous World Series. (1964, 1967.) His ERA over those nine seasons was 3.12; his fielding-independent pitching, 3.10. Among his fellow righthanded pitchers across those seasons, only Hall of Famer Juan Marichal (2.67 ERA; 3.00 FIP) was better.

Gibson pitched seven more seasons after 1968. His ERA over those seven: 3.01; his FIP over the seven: 2.87. You could look at his FIP and argue he was a slightly better pitcher than he’d been before 1968, and that’s without getting another chance to pitch in the postseason before his 1975 retirement.

Let’s look at some of Gibson’s other critical measurements, various key pitching averages, comparing his pre-1968 seasons and his post-1968 seasons:

| Averages |

Sho |

BB |

K |

WHIP |

H/9 |

HR/9 |

BB.9 |

K/9 |

K/BB |

| 1959-1967 |

3 |

78 |

176 |

1.22 |

7.6 |

0.7 |

3.3 |

7.5 |

2.25 |

| 1968 |

13 |

62 |

268 |

0.85 |

5.8 |

0.3 |

1.8 |

7.9 |

4.32 |

| 1969-75 |

3 |

81 |

181 |

1.22 |

7.9 |

0.5 |

3.1 |

6.8 |

2.22 |

Gibson himself rejected the idea, though not impolitely, but even he had to know that even the greatest of the great have had fluke seasons, outlying seasons. (One-time teammate and fellow Hall of Famer Steve Carlton had one in 1972, to name one.) His 1968 is a no-questions-asked outlier, if not a flat-out fluke. His 1967 ERA was 2.98, and that’s despite being rudely interrupted by Hall of Famer Roberto Clemente’s liner breaking his leg that July. Any pitcher’s ERA dropping 1.86 below the previous season’s mark, which is exactly what Gibson’s 1968 ERA did, is a drop comparable to the poor soul who falls from the apex of the Gateway Arch.

And, whether his most stubborn partisans like it or not, Gibson had only too much help both making the Year of the Pitcher and inspiring subsequent rules changes.

You probably remember some of that help better than others. Maybe the help you remember best is Denny McLain, the gifted but self-destructive Detroit Tigers pitcher, credited with 31 wins—the first pitcher to cross the 30 threshold since Hall of Famer Dizzy Dean in 1934, the 31 equaling Lefty Grove’s 31 in 1931.

Those still foolish enough to think those 31 wins (when you get four-plus runs support to work with while you’re on the mound you’d better win thirty-one games) mean McLain was better than Gibson that year (because, wins!), think again:

| |

Sho |

BB |

K |

WHIP |

H/9 |

HR/9 |

BB.9 |

K/9 |

K/BB |

| McLain ‘68 |

6 |

63 |

280 |

0.91 |

6.5 |

0.8 |

1.7 |

7.5 |

4.44 |

| Gibson ‘68 |

13 |

62 |

268 |

0.85 |

5.8 |

0.3 |

1.8 |

7.9 |

4.32 |

Maybe the help you remember second best is another Hall of Famer, Don Drysdale, breaking Walter Johnson’s 55-year-old mark by pitching 58.1 scoreless innings across six complete-game shutouts. Maybe the help you remember third best is yet another Hall of Famer, Carl Yastrzemski, delivering the lowest-ever average (.3005, rounded to .301) for any league batting champion.

Now, here’s some of Gibson’s Year of the Pitcher help that you may not remember quite so well. Such help as:

* The entire Show posting a 2.98 ERA and FIP.

* The American League slugging .339—the lowest in the league since 1915.

* Gibson’s Cardinals pitching 30 shutouts, followed in order by the Mets (25), the Indians (23), the Los Angeles Dodgers (23), and the Giants (20.)

* The whole Show’s combined .237 batting average was the lowest in major league history to that point and lower than the .240 team average of the 1962 Mets. The American League’s .230 remains the lowest league batting average in history.

* Luis Tiant, the Cleveland Indians’ righthander, posting a 1.68 ERA and a 2.04 FIP, both of which led the American League. (McLain’s FIP: 2.53, the lowest of his career by very far.)

* Jerry Koosman, rookie New York Mets lefthander, pitching seven shutouts. (He lost the Rookie of the Year award to Hall of Famer Johnny Bench, a year after the late Hall of Famer Tom Seaver won the award.)

* Ray Washburn (journeyman St. Louis Cardinals pitcher) and Hall of Famer Gaylord Perry (San Francisco Giants) pitching no-hitters on consecutive days, against each other’s teams, in Candlestick Park.

* Everything else meaning nobody sat up bolt upright in amazement when Hall of Famer Catfish Hunter—who managed somehow to avoid posting a sub-3.00 ERA and FIP—pitched a perfect game against the Minnesota Twins in early May. (It probably didn’t help that, in his next start, the Twins battered him for eight earned runs on eight hits and five walks.)

“The 1968 season has been named the Year of the Pitcher,” Angell wrote earlier in his essay, “which is only a kinder way of saying the Year of the Infield Pop-Up. The final records only confirm what so many fans, homeward bound after still another shutout, had already discovered for themselves; almost no one, it seemed, could hit the damn ball anymore.”

You’ll note Angell wrote “almost”: three teams—the Cincinnati Reds (.273), the Atlanta Braves (.252), and the Pittsburgh Pirates (also .252)—managed to hit .250 or better as teams. Gibson’s Cardinals hit .249 collectively; McLain’s Tigers hit two points below the Show average. The worst hitting team in the Show, further evidence of their sad post-1964 Lost Decade, was the New York Yankees—the Bronx Bombers disarmed to Bronx Busts—and their team .214 average.

The two 1968 World Series combatants, the Cardinals and the Tigers, batted .242 between them in a season that wasn’t just the Year of the Pitcher but one in which the last pre-divisional play pennant races were all but decided by the middle of July. Old-school fans probably throve on the idea of a World Series matching a pair of old-time franchises who’d previously played a thriller of a 1934 Series that ended in a trash riot (over Cardinals outfielder Joe Medwick) and a Cardinals triumph.

But the Tigers pitched nineteen shutouts to the Cardinals’ staggering 30 going in—and hung on to beat the Cardinals in seven games only three of which could be called thrillers. Three others were no-questions-asked blowouts, with Gibson and the Tigers’ eventual World Series MVP Mickey Lolich benefiting from one blowout apiece.

McLain himself pitched six shutouts but Lolich—the portly lefthander who lived on a mix of off-speed pitches and a sinkerball that got deadlier as he tired by late innings—pitched four, including three down the stretch after he was restored to the Tigers’ starting rotation in late August. Gibson, though, accounted for almost half his team’s shutouts with thirteen. He’d also pitch the Series’ lone shutout, the Game One in which he broke Hall of Famer Sandy Koufax’s record for strikeouts in a single Series game.

The ’68 Series is also remembered for the two phenomenally-anticipated pitching matchups between Gibson and McLain that turned into mismatches with McLain coming out on the short end. Well, only one of the pair was a real mismatch: Game Four, the Cardinals battering McLain for four runs (three earned) in two and two-thirds, two more runs by Joe Sparma in a third of an inning, then prying John Hiller without an out in the eighth, including Hall of Famer Lou Brock’s three-run double.

That kind of run support must have staggered Gibson, who’d enjoyed 2.8 runs of support while he was in the game during his regular-season starts.

It’s so simple even now to think that when push came to shove Gibson simply out-classed McLain and McLain was exposed as a paper Tiger, but there was a backstory to it: McLain was pitching with shoulder trouble that began when he felt a pop in a 1965 start. And, by 1967-68, McLain was taking copious cortisone shots to pitch with that shoulder. Should you really be shocked, after all, that after another full-out 1969 (and a second straight American League Cy Young Award) McLain’s career took a nose-dive into Lake Michigan?

Some may remember, years after he retired, McLain fuming, “The name of the game back then was you gotta win one for the Gipper. [Fornicate] the Gipper!” He wasn’t referring to Ronald Reagan, either. “McLain’s bitterness was well earned,” wrote Sridhar Pappu in The Year of the Pitcher: Bob Gibson, Denny McLain, and the End of Baseball’s Golden Age. (2017.)

Those cortisone shots would cost him his major league career. The myth that baseball players were tougher and more resilient back in the day, that they were willing to endure anything for the sheer love of the game, is just that—a myth. In truth, they were victims of terrible medical advice, merciless management, and unforgiving fans who believed that a worn-out, hurting arm signaled a kind of moral weakness.

Excessive cortisone administration doesn’t just cause the kind of visual issues that can result in blindness such as afflicts former Mets/Senators/Tigers pitcher Bill Denehy (who joined the Tigers the season after McLain’s departure), who received a multitude of such shots after a shoulder injury in his rookie 1967. Citing pitcher Mike Marshall (reliever in 37 games for the 1967 Tigers; eventual 1974 Cy Young winner who earned a subsequent doctorate in exercise physiology), Pappu wrote ominously:

Marshall even then understood what cortisone is: not a cure-all for pain, but a corrosive that softens the bone and weakens the ligaments. [Marshall] could see McLain growing addicted to it. Despite what doctors might have said, cortisone was more of an analgesic than a curative treatment. And, ultimately, it would destroy McLain’s career.

McLain was reckless, a self-destructive self-promoter, most likely due to the early death of a father who yearned for his son to escape the hard paycheck-to-paycheck labourer’s life and taught that yearning with ferocious, excessive beatings. (Bob Gibson never knew his father, who died three months before he was born, but his older siblings and mother taught him with firm but loving hearts.) Whatever else you’ve read about McLain’s worst, the real cause of his baseball death was his shoulder trouble and his excess dependence on cortisone.

Removing the 1968 World Series from the equation, the question before the house is the same which the political humourist P.J. O’Rourke attached to his book about the 2016 presidential election as a title: How the hell did this happen? Well, this is how the hell the Year of the Pitcher happened:

Hint: Sandy Koufax won the first of his record three MLB Cy Young Awards (it became an each-league prize after Koufax retired) and beat the Yankees twice in that World Series, including the Game One in which he set the strikeout record Gibson broke.

From 1950-1962, the strike zone was between the batters’ arm pits and his knees, however they stood at the plate, whether crouching little pests like Hall of Famers Luis Aparicio and Nellie Fox, or more upright demolition experts like Hall of Famers Mickey Mantle and Willie Mays. Then the Baseball Rules Committee decided the hitters were having too much fun and the pitchers needed a reasonable break.

So, in 1963, they expanded the strike zone, from the top of the batters’ shoulders to the bottoms of their knees. Oops.

That Rules Committee “apparently thought they were, in taking this action, returning the strike zone to what it had been prior to 1950; that, at least, is what they announced at the time,” wrote Bill James in The New Historical Baseball Abstract. “They overshot the mark just a little; the definition used prior to 1950 was from the player’s knees to his shoulders; the new definition said from the bottom of the knees to the shoulders.”

The effect of this redefinition was dramatic. The action was taken, quietly, because there was a feeling that runs (and in particular home runs) had become too cheap. Roger Maris’s breaking Babe Ruth’s single-season home run record contributed to that feeling. The thinking was that, by giving the pitchers a few inches at the top and bottom of the strike zone, they could whittle the offense down just a little bit.

Denny McLain, at the painful height of his career.

Baseball observers and analysts of the 1960s, bless them, didn’t stop to think that, yes, Roger Maris, a compact but muscular lefthanded pull hitter who hit booming high line drives instead of parabolic bombs, did have a delicious short porch at which to aim in Yankee Stadium . . . but he hit one less home run at home in 1961 than he did on the road. And, that five out of Maris’s nine road ballparks were rated pitchers’ parks that year.

James also argued, like Angell, that the ballparks themselves contributed to a game weighted to pitching by the 1960s as a whole and 1968 in particular: every ballpark change between 1930 and 1968 took hits out of the leagues with increasing volume of foul territory. Nor did anyone in either league or from the commissioner’s offices bothered checking height or slope of pitching mounds visibly higher than the rules allowed.

There was also the nocturnal factor. Night ball continued growing. In elementary terms, you tell me how simple it might be to swing on and connect with a 95 mph-plus fastball. You tell me if you’d like to face Bob Gibson, Sandy Koufax, or Nolan Ryan—or even Juan Marichal with that multiple array of windups and leg kicks—in the dead of night no matter how well lit the ballpark might be.

This is the total of night games played in each season from 1963, when the new pitcher-delicious strike zone took effect, through the end of the Year of the Pitcher:

| Season |

Day Games |

Night Games |

+/- Night |

ERA |

| 1963 |

4,209 |

3,837 |

-372 |

3.46 |

| 1964 |

4,326 |

4,055 |

-271 |

3.58 |

| 1965 |

4,402 |

4,197 |

-205 |

3.50 |

| 1966 |

4,120 |

4,385 |

+265 |

3.52 |

| 1967 |

3,986 |

4,442 |

+456 |

3.31 |

| 1968 |

3,731 |

4,309 |

+576 |

2.98 |

The Show played 576 more night than day games in 1968, compared to 456 more night than day in 1967 and 73 more night than day games in 1966. Baseball also played 204 more night games in 1968 than 1963. More to the point: marry that -0.33 drop in the Show’s ERA from 1967 to 1968 to that still-expanded strike zone.

Even allowing the gradual pre-1967 adjustments to night ball and the 3.53 ERA from 1964-66, now should it have been that much of a shock that the season would come in which the pitchers had that tight a grip on the game?

Gibson pitched 23 of his 34 1968 starts at night and threw nine of his thirteen shutouts at night. McLain also pitched 23 night games out of 41 starts in 1968, and he threw five of his six shutouts at night. Tiant, the American League’s ERA/FIP champion, also led the league with nine shutouts. Like Gibson, El Tiante started 34 games in ’68. He started sixteen night games and threw three of his nine shutouts at night. But he also pitched in maybe the most cavernous of the trio’s home ballparks, Cleveland’s Municipal Stadium. (The Mistake on the Lake.)

Let’s look further at 1968’s major league shutout leaders:

| Pitcher |

’68 Starts |

’68 Sho |

Sho-night |

Sho-day |

Sho% |

| Bob Gibson |

34 |

13 |

9 |

4 |

38 |

| Luis Tiant |

32 |

9 |

3 |

6 |

28 |

| Don Drysdale |

31 |

8 |

4 |

4 |

26 |

| Jerry Koosman |

34 |

7 |

4 |

3 |

21 |

| Steve Blass |

31 |

7 |

5 |

2 |

23 |

| Ray Culp |

30 |

6 |

5 |

1 |

20 |

| Ray Sadecki |

36 |

6 |

2 |

4 |

17 |

| Mel Stottlemyre |

36 |

6 |

3 |

3 |

17 |

| Jim Nash |

33 |

6 |

2 |

4 |

18 |

| Dean Chance |

39 |

6 |

4 |

2 |

15 |

| Bill Singer |

36 |

6 |

3 |

3 |

17 |

| Denny McLain |

41 |

6 |

5 |

1 |

15 |

(While I was looking them up, I noticed that if the 1968 Boston Red Sox were smarter, or at least less afraid of vampires, they’d have pitched Ray Culp strictly at night. Culp had a 1.91 ERA after dark but a whopping 4.02 ERA in broad daylight.)

Notice that six of those pitchers had twenty percent or better of their starts result in shutouts; four threw more shutouts at night than in daylight; and, that two—Denny McLain and Ray Culp—threw all but one of their shutouts at night. But if you broaden the cut, and look at all 339 of the Show’s 1968 shutouts, 163 were pitched at night—48 percent. Nearly half the shutouts in 1968 were pitched at night.

That was in a season during which 1,404 games had two runs or less and the Show ERA for those games was 2.99; 1,224 had between 3-5 runs, with an ERA of 2.86; and, a mere 622 featured six or more runs, with a 3.17 ERA. Strangely enough, in 1967 the percentage of shutouts thrown at night was 52 percent—but there were also 113 fewer shutouts (226 total) thrown.

However you care to slice and dice it, the pitcher’s parks coming online between the 1950s and the 1960s, the 1963 strike zone expansion, and the non-existent enforcement of uniform and reasonable mound heights, made it perhaps inevitable that the decade wouldn’t end before such an outlying, fluky season as the Year of the Pitcher was played.

Starting in 1969, the mounds were required to be no higher than ten inches and the requirement was enforced strictly. Also for the first time, ever, the Show’s government mandated protection for the hitters’ visual backgrounds, which until then were dominated by bleachers, center field wall advertisements, or both. Finally, as James’s Abstract reminds us, several teams either moved in the fences or moved home plate out toward the fences.

The official strike zone got re-shrunk, too. Back to its pre-1963 dimensions.

Strangely enough, the Year of the Pitcher’s five no-hitters (Cincinnati’s George Culver and Baltimore’s Tom Phoebus also pitched 1968 no-nos) weren’t the most in any major league season. There were six in 1915 (including Hall of Famer Rube Marquard) and 1917 (including eventual Black Sox confessor Eddie Cicotte and the legendary Babe Ruth-to-Ernie Shore game). There would be seven in 1990.

The five no-nos were just about the only way 1968 wasn’t an outlier: in 1969, after the re-shrunk strike zone and shaved-down pitcher’s mounds, five no-hitters were also pitched—by Hall of Famer Jim Palmer, plus Ken Holtzman, Jim Maloney*, Bob Moose, Bill Stoneman, and Don Wilson.

McLain’s shoulder-compromised demise began in 1970. Even before he was suspended for the season for carrying a gun on a Tigers team flight, his ERA in fourteen starts was 4.63 and his FIP was 5.22. In a miserable 1971 with the Washington Senators, he was not only hung with 22 losses to lead the entire Show, his ERA was 4.28 even if his FIP came down to 4.40. But after a ghastly 6.37 ERA and 5.43 FIP in 1972 (twenty games, thirteen starts, with Oakland and Atlanta), McLain’s career was over.

Gibson was more fortunate. He had seven seasons to pitch following 1969, with a few highs, no more postseasons, and the advent of arthritis and knee trouble. He thought of retiring after 1974, but the end of his first marriage compelled him to pitch 1975, partially to cope and partially because he needed the money. But after he surrendered a grand slam to Chicago Cubs spare-part spaghetti bat Pete LaCock, Gibson retired.

Don Drysdale, who’d already had long-term knee and shoulder issues (Koufax once told a reporter privately Drysdale would have retired if he could have in 1966), proved not long for baseball’s world, too. In early 1969, however, his load finish its final toll, too—his rotator cuff vaporised. With no surgery then available to repair it, Drysdale’s career was history, too.

The Tigers finally won the World Series, with a lot of help from Lolich’s career week and no little help from Curt Flood’s sad mishap in the top of the seventh, the great center fielder losing Jim Northrup’s high liner in the sun for just long enough to reverse on a dime and kick up some grass while the ball out-raced him to the fence for a two-run, scoreless tie-breaking triple.

Perhaps remarkably, considering the season it ended, the Tigers posted a .718 Series OPS with 56 hits, eight home runs, and fifteen total extra base hits. “It was still the Year of the Pitcher,” Angell concluded, “right to the last, but the Tiger hitters had restored the life and noise that seemed to go out of baseball this year.”

————————————————-

* Jim Maloney, like McLain, suffered long-term shoulder trouble but with even less understanding from his team than McLain incurred.

Jim Maloney (right) confabs with Hall of Famer Sandy Koufax.

In 1969, Jim Maloney was pitching for the Reds and losing his war against constant, searing pain. He still had enough to pitch a no-hitter against the Astros, but in the process he hurt his arm just at a time when the team that would come to dominate the next decade really needed him. When pitching in another start against the Mets, he simply didn’t have it in him to go on. He ached so much that he had the gall to ask his manager, Dave Bristol, to take him out of the game. An enraged Bristol—soon to be replaced by Hall of Fame manager [Sparky] Anderson—called a meeting with his pitchers and told them that he wouldn’t accept pain as an excuse, that they simply had to play through it.

“Listen, if a guy’s arm is sore he wouldn’t even be able to throw the ball,” Bristol said. “Right? If he can throw it up to the plate and get somebody out, then it can’t be that sore, so he’s gotta stay in there.”

—Sridhar Pappu, in The Year of the Pitcher.

Once one of the National League’s premier power pitchers—with Hall of Famer Sandy Koufax, he co-led the Show with five shutouts in 1966, and had a 2.70 ERA and 2.68 FIP from 1963-66—Maloney suffered especially under a tragic change in regime.

His first major league manager, Fred Hutchinson, himself a former pitcher, once lifted Maloney while the righthander had a no-hitter going against Koufax, of all people—when Maloney suffered a muscle strain in his arm. “When a fellow has an arm like that,” Hutch told the press, “you just don’t take chances.” That’s one up for Uncle Fred!

But when Hutchinson’s cancer took him out late in the 1964 season, successor managers Dick Sisler and Dave Bristol weren’t so careful with Maloney. By 1967 at least, he, too, was taking numerous cortisone shots. In time, Maloney would have a contentious relationship with teammates, fans, and the press, inflamed by then-Reds GM Bob Howsam questioning his injuries and his commitment.

Ironically, it was a baserunning injury—a torn Achilles tendon in 1970—that put paid to Maloney’s career for all intent and purpose. His last thirteen major league games were as a worn-down, ineffective spot reliever for the 1971 California Angels. After baseball, he worked for his father’s car dealership before his first marriage collapsed as he fought a battle with the bottle.

Maloney sobered up, re-married happily, and became his native Fresno’s director for its Alcoholism and Drug Abuse Council until his retirement.