Then-commissioner Fay Vincent (right) with Hall of Fame relief pitcher Rollie Fingers at the latter’s Cooperstown induction, 1992.

Fay Vincent’s finest hours involved navigating a World Series through an earthquake and navigating George Steinbrenner out of baseball, for a little while, anyway. His worst hour involved overcompensatory overreach and lit the powder keg that imploded his commissionership.

Which was a shame, because Vincent—who died Saturday at 86, after stopping treatment for bladder cancer—usually had his heart in the right place when it came to baseball.

For better and for worse, Vincent in the commissioner’s office he’d never really sought actually believed that baseball’s commissioner was supposed to act in “the best interest of the game.” He also believed the best interest of the game wasn’t restricted to making money for the owners.

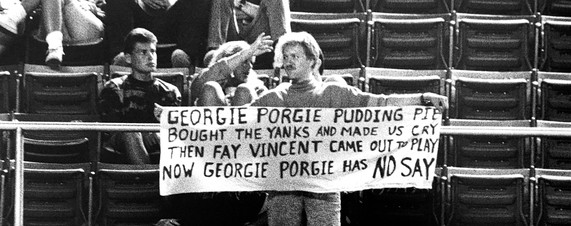

What Steinbrenner got from Vincent, for using a street gambler named Howard Spira to help harvest dirt against Hall of Fame outfielder Dave Winfield, was suspended from baseball, though Vincent cannily allowed the Boss his vanity and let Steinbrenner say he’d merely resign. Biggest favour anyone could have done the Yankees then. With Steinbrenner on justifiable ice, it left Yankee visionaries such as Gene Michael unmolested enough to rebuild the Yankees (“reduced to rubble by the ten-thumbed touch of their owner,” George F. Will wrote on the threshold of the suspension) to greatness.

When the Loma Prieta earthquake hit the Bay Area right smack in the middle of the 1989 World Series (wags took note of the quake’s effect on ramshackle, refrigerating Candlestick Park and called the joint Wiggly Field), Vincent split the difference between the grief of the Bay Area and the necessities of his business. He put the Series on hold for a week. Returned in the rhetoric of healing, the Series finished and the Athletics (hey, yes! they used to be a Bay Area team!) got to finish what they started, a sweep of the Giants.

“Vincent displayed,” wrote Thomas Boswell in the Washington Post of that belief and his actions upon it, when Vincent was forced to resign, “one unexpected tendency that frightened the owners so much that, in recent weeks, they plotted against him . . . ”

When the owners, after years of collusion, shut the spring training camps in 1990, Vincent was a force against the hard-line labour strategy of some owners . . . When many assumed that George Steinbrenner would get off with a light punishment for rubbing shoulders with unsavoury types, Vincent treated the Boss with no more respect than if the owner had been a mere athlete who had gone astray and damaged the game’s reputation for integrity. When he was asked to divide the [1993] expansion spoils, he divided them so fairly that no one was happy. When he thought it was healthy for the game to put teams from the West in the NL’s West division and teams from the East in the East division—a shocking notion that had been discussed for decades—Vincent actually did it, even though one team* (out of twenty-eight) really didn’t like it and threatened to cause lots of legal trouble.

Vincent got into baseball only because his close friend A. Bartlett Giamatti asked. Pretty please, with sugar on it, even. So this man who made his fortune as an attorney, as a chief executive of Columbia Pictures, and as a Coca-Cola honcho after Coke bought Columbia, heeded his longtime friend. (“Coca-Cola surprised even Columbia’s management team of Herb Allen and Fay Vincent by paying $750 million for the studio, the equivalent of nearly twice its stock value at the time,” wrote historian Mark Pendergrast in For God, Country, & Coca-Cola.)

He stood by his man when Giamatti dropped the hammer on Pete Rose. He accepted baseball’s mantle when Giamatti suffered his fatal heart attack eight days after winding up the Rose investigation, and the owners practically begged him pretty please, too.

Alas, the owners would learn the hard way that they hadn’t exactly bought themselves a yes-manperson. If only Vincent hadn’t built them the guillotine into which they’d force him to put his head in 1992.

Vincent’s most wounding flaw was as John Helyar (in The Lords of the Realm) described it: “passively waiting for [some] issues to become a mess instead of getting ahead of the curve on them.” Then, when he did involve himself, enough owners could and did smear him as a stubborn tyrant. Then came the Steve Howe mess.

Once a formidable relief pitcher, Howe became the near-poster boy for baseball’s 1980s cocaine epidemic. And, a six-time loser while he was at it, in terms of baseball standing. Then, in 1991, Howe applied for reinstatement and Vincent gave it to him. Then the Yankees gave him a shot after he set up an independent tryout at their spring camp. The aforementioned Gene Michael said, just as magnanimously, “He’s been clean for two years. I asked a lot of people a lot of questions about him, his makeup, the type of person he is. I feel there’s been a lot worse things done in baseball than bringing Steve Howe back. If it was my son or your son, you’d want to give him another chance.”

At first, Howe more than justified Vincent’s and the Yankees’ magnanimity. He pitched his way onto the Yankee roster and posted the second best season of his career: a 1.68 ERA, a 2.34 fielding-independent pitching rate, and an 0.96 WHIP. A hyperextended elbow ended his season in August 1991, but when Howe opened 1992 with a 2.42 ERA and a 0.45 WHIP, he made Vincent, Michael, and the entire Yankee organisation resemble geniuses.

Except that there was this little matter of Howe being busted in Montana during the off-season on a charge of trying to possess cocaine. Howe had little choice but to plead guilty in June 1992. Almost unprompted, Vincent barred Howe for life.

The Major League Baseball Players Association filed a grievance based on Howe’s having passed every drug test he was called upon to take. Howe’s agent Dick Moss handled the union side of the grievance and brought in a few heavy Yankee hitters—Michael plus manager Buck Showalter and a team vice president named Jack Lawn—as character witnesses.

Oops.

Thinking that Vincent felt as though Howe had just made him resemble a fool after going out on a very long limb for him was one thing. But he struck back like a man whose knowledge of fly swatting involved a hand-held nuclear weapon. He tried to strong-arm Michael, Showalter, and Lawn into changing their testimony the following day. He ordered them flatly to be in his office no later than eleven that morning, never mind that Showalter was already in his Yankee Stadium office prepping for the day’s game against the Royals.

Vincent sent the same orders to Michael and Lawn at home. Michael picked up Lawn, then Showalter, and an attorney Michael called warned them: don’t go to Vincent without a lawyer present unless you’re taking suicide lessons. When they arrived, Vincent told them they’d each “effectively resigned form baseball” because they had dared to “disagree with our drug policy” by acting as Howe’s character witnesses.

Lawn, an ex-Marine who once worked for the federal Drug Enforcement Agency, told Vincent he was sworn to tell the truth and “only testified in accordance with my conscience and my principles.” The commissioner whose conduct rankled those owners who essentially told him, “We don’t need your steenkin’ conscience and principles,” told Lawn—who wrote it on an index card so he wouldn’t forget it—“You should have left your conscience and your principles outside the room.”

An attorney privy to the Yankee trio’s session with Vincent said, “This guy has cooked his own goose.”

Showalter didn’t get back to the Stadium until four minutes before the first pitch. It hit the New York media as hard as the home runs that began a 6-0 Royals lead and helped end things with a 7-6 Yankee comeback win. Three guesses which part of the day mattered more postgame.

If Vincent wanted to mop the floor with The Boss, that was fine by the scribes. But if he wanted to mop the streets with Showalter, Michael, and Lawn, they were going to raise a little hell. They forced Vincent to back off his disciplinary threats. He was also forced, more or less, to order notices posted in baseball clubhouses saying no one should fear retaliation for testifying candidly during grievances.

Those among the owners already itching to dump Vincent got new impetus by his “manhandling of the Yankee Three,” Helyar wrote. “More no-confidence [in Vincent] memos came across [then-Brewers owner Bud Selig’s] fax machine. The conference callers turned to two big questions. One: How much support did they need to fire Vincent? Two: Could they legally fire him?” In order: 1) A two-thirds majority. 2) Yes, long as they paid the man the rest of his contract terms.

After vowing to fight to the end but gauging his falling support, Vincent saved the owners the trouble of executing him when he resigned in September 1992.**

“He vowed,” Boswell wrote, “to fight his backstabbing, leak-planting, disinformation-spreading enemies all the way to the Supreme Court. But, in the end, Jerry ‘I’m Michael Jordan’s Boss’ Reinsdorf of the White Sox, Bud ‘Me? Plot against Fay?’ Selig . . . and Peter ‘I’m Just as Powerful as Dad’ O’Malley of the Dodgers got their way . . . Vincent resigned rather than than drag baseball through the indignity and distraction of a long legal brawl . . . His final act ‘in the best interests of the game’ was, he wrote, ‘resignation, not litigation’.”

Long before the Howe mess, enough owners believed Vincent was too much of a players’ commissioner. Vincent himself said often enough that his largest regret after leaving office was being unable to build what he called “a decent relationship” between the owners and the players.

“I thought somebody would take over after me and get that done,” he told a reporter in 2023. “If I died tomorrow, that would be the big regret, is that the players and the owners still have to make some commitment to each other to be partners and to build the game.”

Selig, of course, became the head of the owners’ executive council, which made him in effect baseball’s acting commissioner. After the owners under his watch forced the 1994 players’ strike, they elected to make him the new commissioner, where he stayed until 2015.

“To do the job without angering an owner is impossible,” Vincent once said. “I can’t make all twenty-eight of my bosses happy. People have told me I’m the last commissioner. If so, it’s a sad thing. I hope [the owners] learn this lesson before too much damage is done.”

Vincent didn’t exactly go gently into the proverbial good gray night, either. His memoir, The Last Commissioner, was a bold if futile wake-up invitation to the game he loved. His later interviews with assorted Hall of Famers and surviving Negro Leagues players led to three books worth of oral history (The Only Game in Town, We Would Have Played for Nothing, and It’s What’s Inside the Lines that Counts).

He tried to leave baseball better than when he found it. If he couldn’t do that, it wasn’t because he failed to speak or act but because enough who mattered failed to listen when he was at his best and overreacted the one time he overreacted himself.

Vincent deserved better than to be pushed out the door under the lash of one bad mistake. May the Elysian Fields angels grant his family comfort and himself a warm homecoming.

————————–

* For the record, that team was the Cubs.

** Steve Howe was reinstated, again, after all. Arbitrator George Nicolau ruled that baseball failed to test Howe “in the manner it promised based on Howe’s documented case of attention deficit and hyperactivity disorder,” as Forbes’s Marc Edelman wrote in 2014. Howe had a none-too-great 1993 but got himself named the Yankee closer for 1994, having a splendid season, the near-equal of his striking 1991-92 work.

His 1995 was anything but, alas. Moved back to a setup role in 1996, he would be released that June after 25 appearances and an obscene 6.35 ERA. He tried one more season in the independent Northern League, with the Sioux Falls Canaries, but called it a career after that 1997 season, after the Giants backed away from signing him following an airport incident in which he was found with a handgun in his luggage.

Almost ten years after his pitching career ended, working his own Arizona framing contracting business, Howe was leaving California for home when his pickup truck rolled over in Coachella, ejected him, and landed on him, killing him at 48. Toxicology reports said there was methamphetamine in his system.

————————-

Note: This essay was published first by Sports Central. A very few small portions were published previously.