Ken Holtzman, one of the prime contributors to the Athletics’ legendary (some also say notorious) three straight World Series titles in 1972-74.

Ken Holtzman was a good pitcher with two distinctions above and beyond being credited with more wins than any Jewish pitcher including Hall of Famer Sandy Koufax. He may have been the last major league player to talk to Hall of Famer Jackie Robinson before Robinson’s death. And, he’s the answer to this trivia question: “Name the only two pitchers in major league history to pitch no-hit, no-run games in which they struck nobody out.”

According to Jason Turnbow’s Dynastic, Bombastic, Fantastic, his history of the 1970s “Swingin’ A’s,” Robinson was at Riverfront Stadium for a pre-Game One World Series ceremony in 1972, commemorating 25 years since he broke the disgraceful old colour barrier. Robinson threw a ceremonial first pitch, then departed through the A’s clubhouse, where he happened upon Holtzman finishing his pre-game preparation.

“Nervous?” Robinson asked the lefthander. “Yes, sir, a little bit,” Holtzman admitted. After some small talk, Turnbow recorded, Robinson handed Holtzman an instruction: “Keep your hopes up and the ball down.” Nine days later, the A’s continued celebrating a World Series title but Robinson died of a second heart attack.

“I was probably the last major leaguer to talk to Jackie Robinson,” Holtzman would remember. Robinson’s advice probably did Holtzman a huge favour; he started Game One and, with help from Hall of Famer Rollie Fingers plus Vida Blue in relief, he and the A’s beat the Reds, 3-2.

A good pitcher who brushed against greatness often enough and became something of a rubber-armed workhorse, Holtzman—who died at 78 Sunday after a battle against heart problems—had two no-hitters on his resume from his earlier years with the Cubs. The first one, in 1969, made him that trivia answer. Four years to the day after Cincinnati’s Jim Maloney pitched a no-hitter that’s the arguable sloppiest no-hitter of all time (Maloney struck twelve out but walked ten), Holtzman joined the No-No-No Chorus.

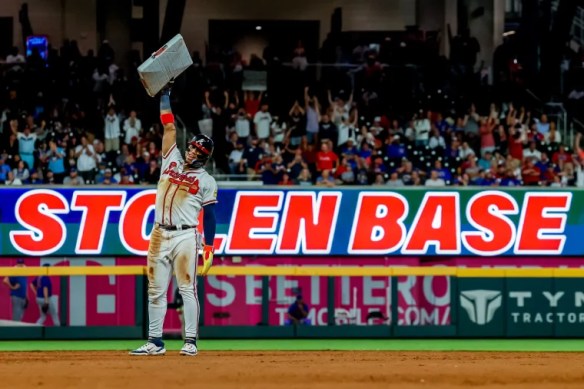

19 August 1969, the Cubs vs. the Atlanta Braves in Wrigley Field, Holtzman vs. Hall of Famer Phil Niekro. While the Cubs got all the runs they’d need when Hall of Famer Ron Santo smashed a three-run homer off Knucksie, Holtzman performed the almost-impossible. He got fifteen air outs (including liners and popouts), thanks in large part to the notorious Wrigley winds blowing in from the outfield. (Hall of Famer Henry Aaron made three of his four outs on the day in the air.) He got twelve ground outs. And he couldn’t ring up a strikeout if he’d bribed home plate umpire Dick Stello begging for even one little break.

It joined Holtzman to Sad Sam Jones of the 1923 Yankees. Jones faced and beat the Philadelphia Athletics in Shibe Park, with both Yankee runs scoring on a two-run single by former Athletic Whitey Witt in the third inning. Jones got fourteen ground outs and thirteen air outs, living only slightly less dangerously than Holtzman did.*

Holtzman took a little more responsibility throwing his second no-hitter, against the Reds on 3 June 1971, the first no-no to be pitched in Riverfront Stadium. This time, he struck six out while walking four, getting ten ground outs and ten air outs each. Clearly he’d learned some things before his Cub days ended.

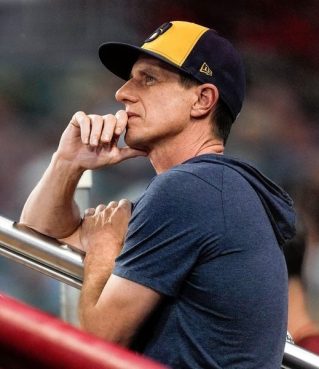

Holtzman, as a young Cub.

He had no trouble learning off the mound, either, graduating with bachelor’s and master’s degrees from the University of Illinois and mastering French well enough to have read Proust in the language. When he moved from the Cubs to the A’s, he even found a unique way to funnel his competitive side when he didn’t have to be on the mound.

Holtzman drew a few teammates toward his passion for playing bridge, including Hall of Fame relief pitcher Rollie Fingers, infielder Dick Green, and relief pitcher Darold Knowles, according to Turnbow. In time, the Oakland Tribune‘s A’s beat writer Ron Bergman would join Holtzman and Fingers in scouting and finding bridge clubs on the road.

“We’d be the only three guys there,” Holtzman once cracked, “three major leaguers playing against 85-year-old women.”

“It was all gray-haired old ladies,” Fingers said. “We’d beat them during the afternoon, and then we’d go to the ballpark and beat a baseball team.”

On the mound, Holtzman arrived with immediate comparisons to Koufax. Being Jewish and lefthanded and arriving in Koufax’s final season made that possible, and impossible. Nobody could live up to a Koufax comparison at all, never mind by way of sharing the same pitching side and religious heritage.

Holtzman didn’t help relieve himself of those when he faced Koufax himself in Wrigley Field, the day after Yom Kippur 1966, and outlasted Koufax, 2-0, taking a no-hitter into the ninth before veterans Dick Schofield and Maury Wills singled off him. Or, when he pitched 1967 as a 21-year-old phenom with a 9-0 won-lost record around the military reserve obligations many players had in his time.

His Cub career wasn’t always apples and honey, alas. Other than the unrealistic Koufax comparisons, there were the military reserve interruptions (he pitched on weekend passes in 1967) and there was his tendency to speak his mind, which didn’t always sit well no matter how much his teammates liked him personally.

There was also dealing with Leo Durocher managing those Cubs, and especially becoming a Durocher target, burning when Durocher accused him of lack of effort. The Cubs’ Durocher-triggered self-immolation of 1969 didn’t make for better times ahead, for either Holtzman or the team. In fact, Durocher’s Cubs author David Claerbaut recorded a conversation Hall of Famer Ernie Banks had with Holtzman as the collapse approached:

Banks had a few drinks with the young southpaw after a game in Pittsburgh. “Kenny,” he said, “we have a nine-game lead, and we’re not going to win it becsuse we’ve got a manager and three or four players who are out there waiting to get beat.”

For the then 23-year-old hurler, the conversation with Banks was chilling. “He told me right to my face, I’ll never forget it. It was the most serious and sober statement I’d ever heard from Ernie Banks—and he was right.” Holtzman’s take was similar to that of Mr. Cub. “I think that team simply wasn’t ready to win. I’m telling you, there is a feeling about winning. There’s a certain amount of intimidation. It existed between the A’s and the rest of the league . . . In Oakland, when we took the field, we knew we would find a way to win. The Cubs never found that way.

After a struggling 1970 and 1971, Holtzman asked for and got a trade . . . to the Swingin’ A’s, for outfielder Rick Monday. A’s manager Dick Williams took to Holtzman at once. So did pitching coach Wes Stock: “I’ve never seen a pitcher throw as fast as he does who has his control.”

Holtzman learned soon enough how the contradictory ways of A’s owner Charlie Finley would make the A’s baseball’s greatest circus—even while they won three straight World Series in which Holtzman had prominent enough roles (and made his only two All-Star teams) and missed a fourth thanks to being swept by the Red Sox in 1975.

His first Oakland season in 1972 didn’t exclude heartache, alas. With the A’s in Chicago for a set with the White Sox, the Munich Olympic Village massacre happened. Eleven Israeli athletes and coaches were held hostage and killed by the Palestinian group Black September.

Proud but not ostentious about his Jewishness, Holtzman and Jewish teammate Mike Epstein took a long, pensive walk before electing to have the A’s clubhouse manager sew a black armband onto one of their uniform sleeves. The two players were stunned to see Hall of Famer Reggie Jackson wearing such an armband as well.

Epstein objected (he’d had previous tangles with Jackson), but Holtzman accepted. Jackson “had contact with Jewish people growing up and was not entirely unaware of Jewish cultural characteristics,” Holtzman said. “So when I saw Reggie with that armband, I felt that he was understanding what me and Mike were going through. He . . . felt it appropriate to show solidarity not only with his own teammates but with the fact that athletes were getting killed.”

In the wake of the Messersmith decision enabling free agency at last (Holtzman faced Andy Messersmith twice in the 1974 World Series and the A’s won both games), owners and players agreed to suspend arbitration while negotiating a new collective bargaining agreement. Oops. Finley offered nine A’s including Holtzman contracts with the maximum-allowed twenty percent pay cuts. What a guy.

Annoyed increasingly by Finley’s duplicities, Holtzman began 1976 as an unsigned pitcher but was traded to the Orioles on 2 April—in the same blockbuster that made Orioles out of Jackson plus minor league pitcher Bill Von Bommel and A’s out of pitchers Mike Torrez and Paul Mitchell plus outfielder Don Baylor.

Holtzman took a 2.86 ERA for the Orioles into mid-June 1976, then found himself a Yankee. He was part of the ten-player swap that made Yankees out of catcher Elrod Hendricks and pitchers Doyle Alexander, Jimmy Freeman, and Grant Jackson, while making Orioles of catcher Rick Dempsey and pitchers Tippy Martinez, Rudy May, Scott McGregor, and Dave Pagan.

As a Yankee, Holtzman landed a comfy five-year deal but picked the wrong time to begin struggling in 1977. A May outing in which he couldn’t get out of the first inning put him in manager Billy Martin’s somewhat crowded bad books. (He didn’t pitch in that postseason, just as he wasn’t called upon in 1976.) Active in the Major League Baseball Players Association as well, that side of Holtzman may have made Yankee owner George Steinbrenner less than accommodating as well.

In 1978, Holtzman again struggled to reclaim his former form and was dealt back to the Cubs. After struggling further to finish 1978 and for all 1979, Holtzman retired. He returned to his native St. Louis, worked in insurance and stock brokerage (the latter had been his off-season job for much of his pitching career), and did some baseball coaching for the St. Louis Jewish Community Center. He even managed the Petach Tivka Pioneers in the Israel Baseball League briefly, walking away when he disagreed with how the league was administered.

Holtzman might not have been the next Koufax, but the father of three and grandfather of four knew how to build unusual bridges toward triumphs on the field. May the God of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob have brought Holtzman home to the Elysian Fields for an eternity living in peace.

* St. Louis Browns pitcher Earl Hamilton also threw a no-hit/no-strikeout game, against the Tigers in 1912 . . . but a one-out, third-inning walk preceded an infield error that enabled Hall of Famer Ty Cobb to score in a 4-1 Browns win. Hamilton did as Jones did otherwise: fourteen ground outs, thirteen air outs (including liners and popouts).