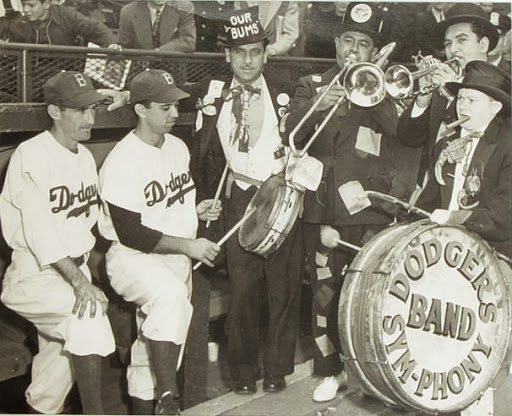

Cacophony in Blue: the Dodgers Sym-Phony Band, plus a pair of unidentified Dodgers, one of whom seems determined to show he has only a slightly lesser sense of time and beat.

When Mr. Cartwright first laid forth the basic dimensions of a baseball field, he had no idea that the game to which he lent his landscape eye would be capable of pastoral play, bursts of excitement, spells of intellect, and . . . enough tomfoolery, foolhardiness, and fool’s gold to inspire poets, pundits, and professional mischief makers alike. The poor man.

Said tomfoolery, foolhardiness, and fool’s gold are not restricted to the field, of course. Baseball’s fans have been (mostly) an agreeable gathering of the aforementioned poets, pundits, and professional mischief makers (not to mention amatuers), patrician and plebeian alike. Baseball’s players have not been immune to mischief making, either.

In regards to which, I hereby open the envelopes and reveal the 2025 winners of the Dodgers Sym-Phony Awards. Named for that crew of Ebbets Field fans who couldn’t carry tunes in backpacks or briefcases alike, but whose clattering, splattering cacophony charmed the living brains out of those who once packed the Brooklyn bandbox on behalf of slapstick one generation and social groundbreaking pennant contention the next.

Donald Trump played Douglas (We now consecrate the bond of obedience) Neidermeyer to Rob Manfred’s Chip Diller when it came to the late Pete Rose . . .

The Animal House Thank You, Sir, and May I Have Another Iron Paddle—To Commissioner Rob Manfred. When a certain president threatened to pardon the late Pete Rose and demanded Rose’s immediate Hall of Fame enshrinement, Manfred met said president in due course. After which, he reached into his heart of hearts, prayed hard, and decided . . . that “permanent” meant mere “lifetime,” after all.

Never mind Rose’s too-well-known violations of Rule 21(d). Never mind his decades of lying about it until or unless it was time to sell yet another autobiography. Never mind the aforesaid president’s erroneous insistence that Rose only bet on his own team to win. (The days Rose didn’t bet were construable by the gambling underground as hints not to bet the Reds those days.)

Once upon a time, such behaviour was believed to be beyond a president and beneath a commissioner. Even if by belief alone. Mr. Trump is not the first and probably won’t be the last president to stand athwart common sense and the law, yelling, “Just try to stop me!” But Mr. Manfred was under no legal, moral, or ethical obligation to satisfy Mr. Trump’s witless hankering, either.

The Quinton McHale PT-73 Crest—To everyone who thought (erroneously) that the too-much publicised torpedo bats of the early 2025 season were, with apologies to George Carlin, going to curve your spine, grow hair on your hands, and keep the country from . . . who the hell knew exactly what?

It didn’t help that the Yankees spent an early season weekend demolishing the Brewers with a few of their batters using the torps.

“Torpedo bats were the talk of MLB in April and May in 2025 and then were never heard from again,” wrote my IBWAA Here’s the Pitch colleague and Almost Cooperstown writer Mark Kolier. “The opening Yankee series versus the Brewers was an anomaly. And players who had great early season success while using a torpedo bat were unable to sustain that success . . . The torpedo bat panacea was fun to talk about while it lasted. But now that’s over.”

We think.

The Maier’s Trophy for Interference Above, Beyond, and Beneath—To Austin Capobianco and John P. Hansen, Yankee fans with onion juice for brains. Banned from all major league ballparks and other facilities indefinitely in January. The crime: Grabbing the wrist of Dodger right fielder Mookie Betts and trying to pry a long foul out of Betts’s glove. Game Four, 2024 World Series.

Dishonourable mention: Barstool Sports writer Tommy Smokes, writing: “The Yankees were down 3-0 in the World Series and you do whatever it takes to extend the at-bat for your guy at the plate.” Today, wrist-grabbing and attempted ball snatching. Tomorrow, shooting when you see the whites of their balls?

The Rose “Make Your Bet and Lie In It” Golden Thorn—To Emmanuel Clase and Luis Ortiz, Guardians pitchers, accused of a pitch-rigging scheme involving throwing particular pitches for particular counts to enable betting on those pitches (it’s called proposition betting) and financial rewards for the bettors.

Reputedly, gamblers won almost half a million on what the pair threw. Clase and Ortiz are charged, too, with earning kickbacks for their, ahem, pitching in.

The Chicken Little Flying Fickle Finger of Fake—To everyone who bleated the sky is falling, it’s the end of the world as we know it, and we don’t feel fine, when Robby the Umpbot made his major league debut last spring training. Robby answered the call of duty when Cubs pitcher Cody Poteet called for his help with one on and Max Muncy (Dodgers) at the plate.

Robby ruled an 0-1 fastball at the knees, called ball one by plate umpire Tony Randazzo, was in fact strike two. Nobody threw lightning bolts down from the Elysian Fields.

The Clarence Bethen-Wile E. Coyote Brass Stethoscope for Injuries Straight Outta Looney Tunes—Named in honour of 1) the pitcher who forgot his false teeth were in his back pocket and slid into second base with a bite on his butt; and, 2) the clod of a canine (Famishius slobbius) who kept Acme in business for eons buying their constantly-backfiring weapons and traps:

* Mookie Betts (Dodgers)—A nocturnal stroll to the reading room turned into a toe fracture. The Mookie Monster missed four games as a result. He opined that he thought we’ve all suffered toe fractures from nocturnal bathroom breaks. I’d like to see the roll call first. And, whom among them might have sung “Midnight Stroll.”

* Zack Littell (Rays)—He learned (or re-learned) the hard way how not to use your head while parenting. Chasing his son around an inflatable slide park, he plowed into scaffolding not padded for play. Let’s guess his favourite song wouldn’t be “Ring My Bell” for a long enough while.

* Jose Miranda (Twins)—Sent back to AAA after a viral baserunning mishap, he went to Target first. (Bad name, in this instance.) He needed bottled water. He reached high for a case of it. He couldn’t stop it from tumbling down. Four weeks on the injured list with a strained left hand, then cut loose entirely when he returned without hitting much else. I submit that nobody had the nerve to play him “I Want to Hold Your Hand.”

* Mariano Rivera (Old-Timers)—The Hall of Fame Yankee relief legend suffered a torn Achilles tendon . . . while pitching in a Yankees Old-Timer’s Day game. You guessed it: I don’t think his favourite song last year was “Things Ain’t What They Used to Be.”

* Ryan Weathers (Marlins)—His pre-game stroll around the mound brought foul weather. He’d thrown his final warmup toss, then turned right to take the stroll. His catcher Nick Fortes threw up the middle to start the round-the-horn routine. The ball didn’t make it. It hit Weathers flush on the left side of the head.

Then, when he shook it off and pitched three innings, Weathers strained his lat and missed three months. I’m going to guess the poor guy’s favourite song is not “Stormy Weather.”

Wishing them and all no further embarrassing wounds, pinpricks, or fractures. And, wishing you from there (and here) a happy New Year, a damn-sight-better-than-the-old-one New Year, and a 2026 baseball season to come in which there’s no foolishness like (mostly) harmless foolishness.