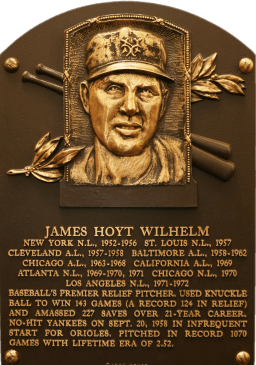

What’s this bland “Relief Pitcher of the Year” stuff? How about the BBWAA name their new (and overdue) reliever awards for Hall of Famers Billy Wagner (National League) and Hoyt Wilhelm (American League; yeah, I know he’s shown with a New York Giants hat, but he did pitch most of his career in the AL by a hair . . . )

Well. The Baseball Writers Association of America has decided that relief pitchers need a BBWAA award of their own. They’re calling it the Relief Pitcher of the Year Award. Maybe this is the one to which people will pay attention. Maybe not.

The name is about as inspired as when the BBWAA changed the name of the J.G. Taylor Spink Award for Hall of Fame baseball writers to the Career Excellence Award. At least MLB, which already awarded an annual prize to the men of the pen, named their awards for a pair of Hall of Fame relief pitchers, Trevor Hoffman (National League) and Mariano Rivera (American League).

Except that nobody pays real attention to the Hoffman and Rivera Awards, noted Jayson Stark (Hall of Fame writer), who’s been agitating for the Relief Pitcher of the Year Award for a very long time.

But Stark also noted that, well, nobody quite knew how to evaluate relief pitchers reasonably. “And why does that matter?” he asks, then answers:

Because if you look at Hall of Fame voting over the past couple of decades, it couldn’t be more obvious that voters can’t figure out how they’re supposed to go about determining what constitutes a dominant, Hall of Fame reliever.

We elected Rivera and Hoffman. We just elected Billy Wagner, but it took us 10 years to do that. So clearly, the voters need help. And the current awards aren’t providing any of that help because this trend is only getting worse.

This much we do know; or, at least, ought to know: the save statistic is close enough to useless. When writing Smart Baseball, Keith Law singled the save out for a chapter of its own to demonstrate it was nothing more than “[Jerome] Holtzman’s Folly,” named for the Chicago sportswriter who invented it in the first place. It was a classic case of the best intention yielding the worst result.*

“If anyone tried to introduce a statistic like the save today,” Law wrote, “he’d be laughed all the way to a cornfield in Iowa.”

The stat is an unholy mess of arbitrary conditions, and doesn’t actually measure anything, let alone what Holtzman seemed to think it measured. Yet the introduction of this statistic led to wholesale changes in how managers handle the final innings of close games and in how general managers build their rosters, all to the detriment of the sport on the field, and perhaps to pitcher health, as well.

Not to mention the health of common sense, what remains of it.

You think arguments involving Cy Young Awards to pitchers who “win” the most games instead of pitchers who were really the best pitchers in their leagues were somewhere between the ridiculous and the absurd? (Anyone who tells me Bartolo Colon deserved the 2005 American League Cy Young Award over Johan Santana had better come with stronger ammunition than Colon’s 21 “wins.” Colon’s fielding-independent pitching rate [FIP] of 3.75 and his ERA of 3.48 weren’t Santana’s major league-leading 2.80 FIP or his 2.87 ERA. There was also the little matter of Santana leading the Show with 238 strikeouts and the AL with an 0.97 walks/hits per inning pitched [WHIP] rate. Case closed.)

How about arguments over relief pitchers with a duffel bag full of “saves” versus the relief pitchers who actually pitched better? Remember Joe Borowski? As a Cleveland Indian in 2007, Borowski led the American League in “saves” with 45 . . . but his FIP was 4.12 and his ERA, 5.07. And that’s before you see where the guys at the plate hit .289 againat him. If that didn’t kill the save, Craig Kimbrel in the 2018 postseason should have.

Kimbrel pitched 10.2 innings and was 6-for-6 in save opportunities. Sounds like the future Hall of Famer he’s still seen to be by some, right? Now, look deeper: Cardiac Craig allowed nineteen baserunners, posted a 5.90 ERA, and a 5.07 FIP . . . and the World Series-winning Red Sox probably felt that was tantamount to the guy who threw the man overboard an anchor and then dove in to pull him out of the water.

Zach Britton. Toronto still blesses then-Orioles skipper Buck Showalter for managing to the save stat instead of what was right in front of him in the 2016 AL wild card game, and leaving Britton—the 2016 season’s best relief pitcher—in the bullpen . . .

And I haven’t even mentioned the managers who take the nebulous save stat as such gospel they manage to it instead of to the game situation in front of them. The no — “save” situation kept Buck Showalter from even thinking about Zach Britton, baseball’s unarguable best relief pitcher in 2016, with two on and Edwin Encarnacion checking in at the plate in the bottom of the AL wild card game 11th in Toronto. Blue Jays fans still bless the name of Showalter when they remember the monstrous 3-run homer Encarnacion hit to send the Jays to the division series.

Based on what little has been revealed so far otherwise, my guess is that the voting writers will take anything but “saves” into consideration. As they should. If they were to ask me, I’d say it should be some sort of points combination based upon FIP, the batting averages against, their leverage situation pitching, their strikeout-to-walk ratios, and their WHIPs.

Let them have at it post haste.

Because the next time I hear someone tell me Chipper Flippersnapper was the best reliever in baseball because he got all those “saves” even if his ERA/FIP combination was higher than the moon, the batting average against him resembled Ralph Kramden’s weight, and he worked as though he’d learned leverage pitching at the Craig Kimbrel School of Anchor-Throwing, I’m going to throw an anchor or three. And a few other things.

(Maybe I’ll just throw two words out: Mike Williams. 2003: Williams, lifetime 4.49 FIP, named an All-Star because the rules said the woebegone Pirates needed one and he had 25 saves at the break. But he also walked three more than he struck out and carried a 6.44 ERA. One week later: ERA down to a mere 6.27; FIP down to a measly 5.55; the Pirates traded him to the Phillies for a rosin bag and Williams’s career ended after that season. )

And for God’s sake give the new BBWAA awards worthy names. How about the Billy Wagner Award for the National League? How about the Hoyt Wilhelm or Rollie Fingers Award for the American League? Relief Pitcher of the Year? That’s about as inspiring or spirited as a tub of chicken fat.

—————————————————————————————————–

* Historical revision: Longtime Pirates relief ace Elroy Face still inspires oohs-and-aaahs over his 1959, when he “won” eighteen games and “lost” only one. The aforementioned Jerome Holtzman dreamed up a save stat in the first place because of Face.

“Everybody thought he was great,” said Holtzman in 1992. “But when a relief pitcher gets a win, that’s not good, unless he came into a tie game. Face would come into the eighth inning and give up the tying run. Then Pittsburgh would come back to win in the ninth.”

According to Anthony Castrovince in A Fan’s Guide to Baseball Analytics, Holtzman “knew the dirty truth about Face: He had allowed the tying or go-ahead run in 10 of his 18 victories. In five of his eventual ‘wins,’ he had entered the game with a lead and left without one.”

It almost seems a tossup between which nebulous statistic is worse: the pitcher “win,” or the relief pitcher save. God bless all 97 years old of him still living, but Elroy Face’s 1959 is evidence on behalf of both.

—————————————————————————————————

First published in a slightly different version at Sports Central.