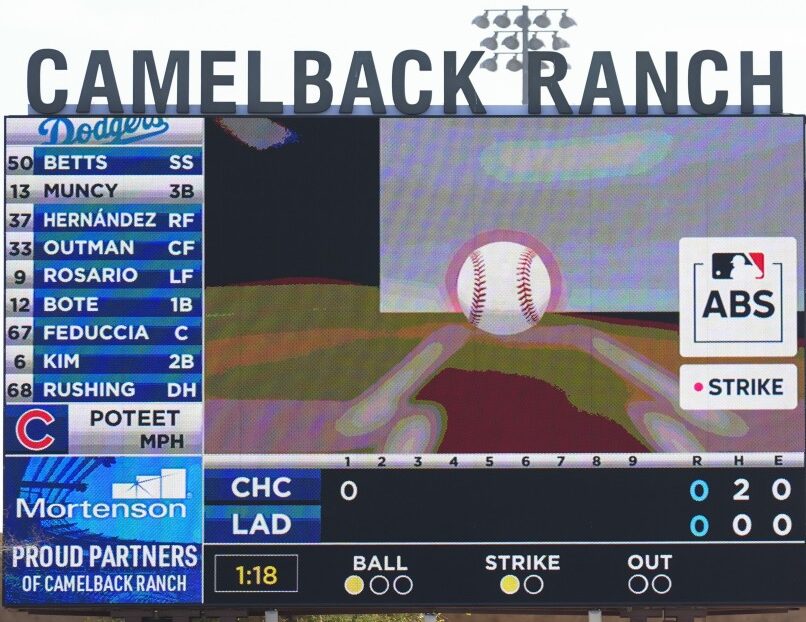

The first MLB deployment of Robby the Umpbot–Cubs pitcher Cody Poteet getting a ball call turned to a strike against the Dodgers’ Max Muncy.

Cody Poteet. Remember the name of this Cubs righthanded pitcher. No, he didn’t surrender three World Series home runs to Babe Ruth in the same game, he didn’t try to start a World Series game the day after pitching four innings in relief, and he didn’t pitch a no-hitter in which he got credit for such a performance despite his defense recording every last out in the game.*

No, Poteet was first on the mound to call for—and win—a ball/strike challenge with aid and comfort from Robby the Umpbot. Even if it was in a spring training exhibition game.

Poteet had Mookie Betts aboard and nobody out in the bottom of the first when he threw Max Muncy a fastball at the knees on 0-1. Home plate umpire Tony Randazzo called it ball one. Poteet said, “Not so fast” . . . and called immediately for Robby the Umpbot’s help. Well, now. The videoboard showed the pitch most certainly did hit the strike zone by the rule book. 0-1 went to 1-1. Muncy ended up looking at strike three not far from the same knee-high location.

Know what happened after that? How about what didn’t happen?

The sky didn’t fall. The earth didn’t move, under their feet or anyone else’s. There were no known tidal waves reported on any world coastline. Donald Trump and his predecessor Joe Biden didn’t suddenly become men of reason and wisdom. The flora and the fauna didn’t make mass entries on the endangered species lists.

About the only unlikely thing to happen from that overturned ball call was the Cubs going forth to batter the world champion Dodgers, 12-4, to open spring exhibition season. They turned a 3-0 Dodger lead after two into a six-run third, added two in the fifth, one in the seventh, and three in the eighth. The only Dodger response was an eighth-inning RBI double.

You might be happy to know that Poteet had an ally on his call for Robby’s review: Muncy himself. “When that ball crossed, I thought it was a strike right away and he balled it,” the Dodger third baseman said postgame. “I look out there and he’s tapping his head and I went, ‘Well, I’m going to be the first one’.”

And, just as with the advent of replay elsewhere, guess what else didn’t happen? The game itself wasn’t delayed unconscionably. Muncy certainly didn’t think so. In fact, he doesn’t mind Robby at all. Neither did Randazzo, seemingly.

“It’s a cool idea,” Muncy said. “It doesn’t slow the game down at all. It moves fast. The longest part was Tony trying to get the microphone to work in the stadium.” Meaning, Randazzo announcing the ruling to the Camelback Ranch crowd.

Come the eighth inning, the Cubs called for another challenge. This time, catcher Pablo Aliendo thought Frankie Scalzo, Jr.’s sweeper nicked the top edge of the zone for strike three with Sean McClain at the plate. Not quite, Robby ruled this time. Ball four.

The rule for deploying the automated ball/strike system (ABS), as it’s called officially, is that only three on the field (pitcher, catcher, or batter) can call for Robby’s opinion and each team gets only two challenges thus far. If the challenging team wins, as the Cubs did, they keep the challenge. When the system was brought online in the minors, the estimates became that the average such challenge was (wait for it!) seventeen seconds.

Neither Poteet nor Muncy were new to Robby, according to The Athletic‘s Fabian Ardaya. Poteet started ten times in the Yankee organisation last year, at Scranton-Wilkes Barre; Muncy saw it while on a rehab assignment off a wrist injury. Muncy’s only issue then was, as he put it to Ardaya, “the technology wasn’t entirely there.”

There’d be certain pitches that you would see and you’d look up on the board and it’d have it in a completely different spot . . . Even the catcher would come back and be like, ‘Yeah, that’s not where that ball was.’ The technology isn’t 100 percent there, but the idea of it’s really cool.

Critics (they were legion) feared Robby the Umpbot would penalise too many solid umpires while punishing not enough errant ones. One conclusion Robby’s early works has stirred is a revelation that might be just as jarring, as The Wall Street Journal‘s Jared Diamond puts it: the players themselves, from the mound to the plate, don’t know the strike zone as well as they think.

“Unlike the replay rules already in place, where managers initiate appeals from the dugout after having time to deliberate,” Diamond writes, “ball-strike challenges have two key differences: They can only come from the pitcher, catcher or batter—and they must happen immediately.

“The result is a format that inserts elements of both strategy and personality into the game even while adding automation. That’s because ultracompetitive, often emotional professional athletes aren’t always particularly good at knowing the right time to ask for a challenge.”

On-field embarrassment comes in infinite forms. Dodgers pitcher Landon Knack, who got knuked by the Mets in last fall’s National League Championship Series, told Diamond of times during his AAA-level days when he challenged pitches from frustration and regretted them at once. “All Knack could do,” Diamond writes, “was stand on the mound and watch the scoreboard animation showing the location of the ball, as everybody in the stadium saw that he was embarrassingly wrong.”

It’s something along the line of the store manager calling la policía after showing up at the bank without the bag full of the day’s cash proceeds, only to double back and realise he or she dropped the bank bag in the parking lot on the way to the car—with the whole thing caught on the store’s security cameras.

Other kinks in the system may well include the choice of players who get to call Robby for help. Diamond says AAA-level managers and players agree on the one who shouldn’t: the pitchers. Knack himself admits, “Pitchers are horrible at it.” Said a Dodgers AAA catcher, Hunter Feduccia, “We probably had a 90 percent miss rate with all the pitchers last year.” Admitted a Royals AAA pitcher, Chandler Champlain, “Being biased as a pitcher, I think anything close is a strike.”

Advises Jayson Stark, The Athletic‘s Hall of Fame writer, “Don’t be That Guy whose heat-of-the-moment challenge decisions leave your teammates shaking their heads and calling you names you won’t want to see displayed above your locker. Be smart. Be cool. Be thoughtful. And control those emotions!”

(Some hitters have been known to have dubious strike zone sense, too. Once upon a time, Hall of Fame catcher Yogi Berra had an impeccable strike zone sense behind the plate . . . and a notorious lack of it at the plate. Maybe the best bad-ball hitter of his time, Berra was questioned postgame about a pitch nowhere near the strike zone or even Yankee Stadium’s postal code that he’d smashed for a home run regardless. Bless his heart, Yogi insisted the pitch was a letter-high strike.)

Relax. Robby’s getting a spring training Show tryout only for now. He’s not expected to spread his wings over the regular season Show until 2026 at minimum.

But if the only kinks in the system other than coordinated calibrations thus far are figuring out who should make the challenges and who shouldn’t, you’d have to say Robby’s going to be in good shape and the umpires are going to be in better shape. (They’ll get immediate reminders of the rule book, as opposed to the “individual” strike zone.) And, the game is going to be in the best shape.

* For the record, the Cub pitchers who delivered those non-feats were, in order, Charlie Root (1932), Hank Borowy (1945), and Ken Holtzman (1969).

This essay was written for and first published by Sports Central.