‘Tis the season to kvetch, complain, and fume. At least, on baseball social media. Spend enough time there and you’d think the glass can’t possibly be half empty because the water isn’t up that high in the first place.

‘Tis the season to kvetch, complain, and fume. At least, on baseball social media. Spend enough time there and you’d think the glass can’t possibly be half empty because the water isn’t up that high in the first place.

Show me a team that makes a good or at least impressive move, I’ll show you half or more of their fan base predicting the End of Their World As They Wish They Knew It. You don’t want to know what those people think if their team makes a dubious move. (Though none have called for retroactive abortions or executions. Yet.)

Show me a team that hasn’t hoisted a World Series trophy since the second Reagan or the first Bush administrations, I’ll show you fans who think any success they’ve had since can only be mistakes—and the World Series trophies they did hoist were figments of their imagination.

(Of course, show me a Yankee fan who no longer believes his or her team is entitled to reach the postseason every season, and I’ll show you a million Yankee fans who think that individual needs to burn in effigy, boil in oil, cop a squat in the electric chair, and lose his or her head in the guillotine—all at the hands of the late George Steinbrenner.)

I get it. I’ve gotten it for a very long time. Some people can never be satisfied. Including and especially baseball’s incumbent commissioner who thinks that, when his mission isn’t making sure the good of the game means making money for its owners, his mission is making damn sure baseball appeals almost solely to those fans at the ballpark to whom a ballgame is just an occasional disruption to their cell phone lives.

Listen up, Commissioner Pepperwinkle. I didn’t mind the larger bases. I learned to live with the pitch clock as it was in 2023. But shortening the clock up even more? You didn’t see enough pitchers’ adjustments resulting in a few too many injuries in a time when throwing hard still supercedes throwing with brains and real strike zone knowledge a little too often?

And I’m long fed up with your incessant expansion of the postseason to the point where championship means applesauce. You’re thrilled that baseball’s eighth-best team of 2023 beat its twelfth-best in the World Series? I don’t mind the Washington Senators of Texas winning the Series at all. What I do mind is a system that tells baseball’s six best teams not so fast, you ain’t getting near the championship rounds until you prove yourself against the top also-rans all over again.

I miss real pennant races. I don’t like watching stretch drives dominated by the thrills and chills of watching teams fighting to the last breath to finish a season . . . in second or third place. I hope against hope that you, Pepperwinkle, mean business about expansion with two more teams. I hope someone pounds into your skull that that should be followed by two major leagues with two eight-team conferences of two divisions each.

I miss real pennant races. I don’t like watching stretch drives dominated by the thrills and chills of watching teams fighting to the last breath to finish a season . . . in second or third place. I hope against hope that you, Pepperwinkle, mean business about expansion with two more teams. I hope someone pounds into your skull that that should be followed by two major leagues with two eight-team conferences of two divisions each.

Then, I hope that same someone pounds into your head that regular-season interleague play has graduated from nuisance to horror. That the free cookie on second base to start each extra half-inning has graduated from bad joke to unacceptable. That the real problem with times of games was and remains excessive broadcast commercials. That all the above means you’re not off the hook just because you gave in to reality and made the designated hitter universal at long enough last.

And, the next time a witless team administration censors a broadcaster over a factoid the team itself provided him, you’d better have a lot more than a deafening silence with which to answer that.

Now, having unburdened myself of all the above, would anybody object to my showing more than a little gratitude? I’m 68 years old. I’ve been a baseball fan since the 1961 World Series and, especially, the 1962 Mets. And I can complain about a lot of what I’ve seen over those years.

I can complain about the disgraceful bids to stain Roger Maris’s and Henry Aaron’s pursuit and passings of the Sacred Babe (single season and career, respectively) as all-time home run hitters. The Yankee double switch that dumped Yogi Berra after managing them to a pennant in his first year trying. The disgrace of putting deceased Cub second baseman Ken Hubb’s photograph on living Cub pitcher Dick Ellsworth’s 1966 baseball card. The Year of the Pitcher.

The dessication of the Hall of Fame thanks to the cronyism of the old Veterans Commmittee when Frankie Frisch and Bill Terry ran it like an ongoing Old-Timers’ Day of their old Giants and Cardinals buds. The hijacking of the second Washington Senators to Texas. Ten Cent Beer Night. Disco Demolition Night.

Bowie Kuhn’s insane blockage of Charlie Finley’s fire sale to include a hard cap on player sales that helped, not hindered salary inflation and hindered, not helped less-endowed teams from surviving while rebuilding. The 1980 pension realignment that froze all pre-1980 short-career major league players out of full pension and health benefits.

Bowie Kuhn’s insane blockage of Charlie Finley’s fire sale to include a hard cap on player sales that helped, not hindered salary inflation and hindered, not helped less-endowed teams from surviving while rebuilding. The 1980 pension realignment that froze all pre-1980 short-career major league players out of full pension and health benefits.

The drug scandals of the 1980s and the Wild West Era of actual/alleged performance-enhancing substances. Pete Rose vs. Rule 21(d). George Steinbrenner vs. a) common baseball sense and b) Dave Winfield. The Wave and the Tomahawk Chop. The mid-to-late 1980s collusion. The owners imposing one of their own as commissioner and pushing the players into the 1994 strike. Álex Rodríguez trying to sue his way out of discipline for his Biogenesis involvement—and baseball government’s parallel shenanigans tainting the probe anyway.

Underqualified Harold Baines and Jack Morris elected to the Hall of Fame while eminently qualified Dick Allen and Lou Whitaker still await their Era Committee review and overdue election, Allen posthumously. Tanking. Astrogate. Domestic violence cases. The pending hijack of the Athletics from Oakland to Las Vegas, eyes wide shut.

Yes, I have had a truckload to complain about in my baseball loving lifetime. But I also have about two planeloads about which to feel grateful for having seen.

I’ve seen Arriba, the Big Hurt, Big Papi, the Big Unit, the Bird, Blue Moon, two Bulldogs (Jim Bouton, Greg Maddux), Capital Punishment, two Cha-Chas (Orlando Cepeda, Keith Hernandez), one Choo Choo, the Chairman of the Board, the Commerce Comet, Crash, Ding Dong Bell, Dr. K, Dr. Strangeglove, El Tiante, the Express, the Franchise, the Greek God of Walks, Hoot, the Hoover, the Human Rain Delay, Jack the Ripper, the Kid, the Kingfish, Kitty, Knucksie, Kong, La Maquina, the Left Arm of God, the Man of Steal, Marvelous Marv, Mr. Cub, Mr. October, Mr. November, Mr. Padre, the Monster, Moose, Oil Can, Pops, the Rock, the Say Hey Kid, the Spaceman, Stretch, Sudden Sam, Sugar Bear, Sweet Music, Vincent Van Go, the Vulture, the Wild Thing, and the Wizard of Oz. Among others.

I’ve seen the Cinderella Red Sox, El Birdos, the Miracle Mets, the Swingin’ A’s, the Big Red Machine, the Pittsburgh Lumber Company, the Bronx Zoo, Harvey’s Wallbangers, the Hum Babies, the Nasty Boys, the Philthy Phillies, the Idiots, and the Baby Sharks.

I saw Mike Trout do things unseen since the Mantle-Mays era and secure a Hall of Fame berth before his body began to betray him little by little. I’ve seen Shohei Ohtani on the mound and at the plate, a one-man avatar of the old saying, “Good pitching beats good hitting—and vice versa.” (You wonder, once in awhile, what would happen if Ohtani the pitcher could ever face Ohtani the hitter.)

I saw Curt Flood fire the Second Shot Heard ‘Round the World one not-so-foggy Christmas Eve and Andy Messersmith finish what Flood started.

I saw Curt Flood fire the Second Shot Heard ‘Round the World one not-so-foggy Christmas Eve and Andy Messersmith finish what Flood started.

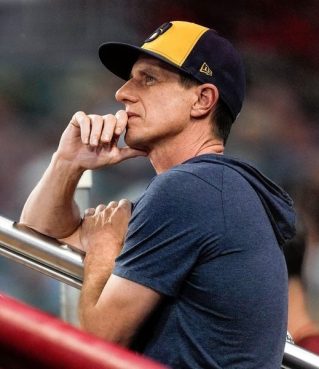

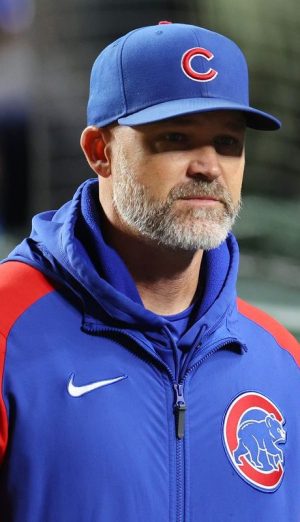

I saw Casey Stengel keep the heat off the infant Mets he managed while the organisation built itself into something beyond baseball’s greatest traveling comedy. I saw managers stolid (Walter Alston), smart (Bruce Bochy, Davey Johnson, Tony La Russa), snarky (Tommy Lasorda, Earl Weaver), self-defeatingly short-sighted (Billy Martin), and sadistic (Leo Durocher). I saw teams trying to win one for an ill-fated manager (the 1964 Reds, as Fred Hutchinson was dying of cancer) and teams actually winning one despite their manager. (The 1980 Phillies, under Dallas Green’s whiplash.) I saw courageous grace under the fire of insidious disease from Michael Weiner (executive director, Major League Baseball Players Association, refusing to let brain cancer dull his love of the game) and see it from Sarah Langs (ALS impacts her body, but not that acute, instructive, engaging mind).

I saw Jackie Robinson dream aloud of the day he might look to see a black manager in a major league dugout. I saw baseball’s first black manager (Frank Robinson) inserting himself into the lineup by popular demand in his first game managed—and hitting one out his first time up. I saw baseball’s third black manager to win a World Series (Dusty Baker) after taking over a scandal-shredded team of Astros and leading them straight, no chaser to the Promised Land.

World Series that transcended time and place and even history: the 1963 and 1965 Dodgers, the 1966 Orioles, the 1967 Cardinals, the 1968 Tigers, the 1969 Mets, the 1971 Pirates, the 1975 Reds and Red Sox, the 1979 “Fam-I-Lee” Pirates, the 1985 Royals, 1986 Mets, the 1990 Reds, the 2002 Angels, the 2004 Red Sox (the aforementioned Idiots), the 2011 Cardinals, the 2014 Giants, the 2016 Cubs and Indians, the 2019 Nationals.

Carlton Fisk’s body-English Game Six walkoff World Series home run. The pennant winners hit by Chris Chambliss (a walkoff), Aaron Boone (2003 ALCS), and José Altuve (2019 ALCS). David Freese sending a Series to a Game Seven with a leadoff eleventh-inning blast. Joe Carter winning the 1993 Series with a bomb.

Poignant farewells. Sandy Koufax’s retirement press conference. (On my eleventh birthday, no less.) Mickey Mantle’s Yankee Stadium farewell. Willie Mays’s farewell at Shea Stadium. (Willie, say goodbye to America.) Brooks Robinson’s at old Memorial Stadium. (Around here, people don’t name candy bars after Brooks Robinson—they name their children after him.) Tom Seaver’s at Shea. (He ran from the microphone to the mound and took bows from all four possible sides of the park.) Mike Schmidt’s mid-season goodbye press conference.

Poignant farewells. Sandy Koufax’s retirement press conference. (On my eleventh birthday, no less.) Mickey Mantle’s Yankee Stadium farewell. Willie Mays’s farewell at Shea Stadium. (Willie, say goodbye to America.) Brooks Robinson’s at old Memorial Stadium. (Around here, people don’t name candy bars after Brooks Robinson—they name their children after him.) Tom Seaver’s at Shea. (He ran from the microphone to the mound and took bows from all four possible sides of the park.) Mike Schmidt’s mid-season goodbye press conference.

Hall of Fame speeches admonitory (Ted Williams throwing the gauntlet down on recognising and honouring Negro Leagues greats “who are not here only because they weren’t given the chance”), amiable (Yogi Berra), appreciative (Ozzie Smith, living and self-reflecting the dream), appalling (Earl Averill zapping the Hall over how long it took for him to be elected), and athwart all precedent. (The invaluable Roger Angell, the first non-daily beat writer elected as a Spink Award Hall of Famer.)

Voices of the game in the broadcast booths running the spread from shameless homers (Ken Harrelson, Bob Prince, Ron Santo, John Sterling) to smooth operators (Curt Gowdy, Tim McCarver, Lindsey Nelson), spiritual billy goats gruff (Harry Caray), and spirits beyond these dimensions. (Vin Scully.) Writers who gave it genuine literature: Angell, Dave Anderson, Ira Berkow, Thomas Boswell, Jim Bouton, Jim Brosnan, Alison Gordon, Bill James, Pat Jordan, Roger Kahn, Ring Lardner, Jane Leavy, Jim Murray, Joe Posnanski, Shirley Povich, Damon Runyon, Claire Smith, Red Smith, Jayson Stark, George Vecsey, George F. Will.

Koufax proving practise makes perfect. (His fourth no-hitter in each of four straight seasons: a perfect game.) Aaron yanking the Sacred Babe to one side while making chumps out of the racists who tried to intimidate him and of his own team trying to demean him by placing the box office ahead of proper competition.

Koufax proving practise makes perfect. (His fourth no-hitter in each of four straight seasons: a perfect game.) Aaron yanking the Sacred Babe to one side while making chumps out of the racists who tried to intimidate him and of his own team trying to demean him by placing the box office ahead of proper competition.

The Express striking the Man of Steal out to reach 5,000 career punchouts. The long-since-tainted 1998 single-season home run chase. (We loved it, until we didn’t.) Aaron Judge nudging Maris to one side as the American League’s single-season home run king. Albert Pujols delivering the only farewell tour that matters: no pomp, circumstance, or conscious tributaries, just hitting 71 percent of his 24 homers that year in the season’s final two months.

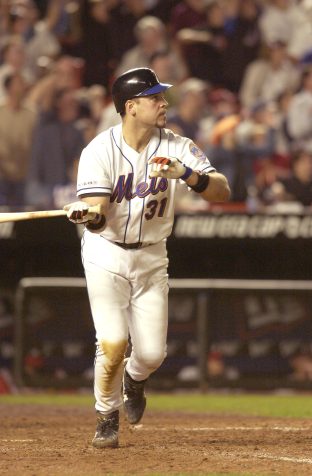

Mike Piazza sending a 9/11 shocked and staggered New York and nation into a rip-roaring frenzy when, late in the Mets’ first home game after baseball resumed following a break, he sent one banging off a television camera scaffold behind Shea Stadium’s left center field fence.

Even this year’s World Series, for all the flawed foundation of the postseason that led to it. Scratching the Rangers off the list of franchises lacking even one World Series trophy, it’s possible to believe that, in my lifetime, I may yet see World Series trophies hoisted by teams from Colorado, Milwaukee, San Diego, Seattle, and Tampa Bay.

Ballparks in which I’ve sat watching games. The Polo Grounds and Shea Stadium. Old Rosenblatt Stadium in Omaha, when the team was the Royals’ Triple-A farm. Wrigley Field. Lackawanna County Stadium. (Pennsylvania, when the Triple-A team was the Scranton-Wilkes Barre Red Barons and a Phillies affiliate.) Tiger Stadium. Camden Yards. Angel Stadium. Dodger Stadium. Cashman Field. (When Las Vegas’s Triple-A team was a Dodgers, then Blue Jays, then Mets affiliate.) Las Vegas Ballpark. (For the Triple-A Aviators.)

If all the foregoing says nothing else, it ought to say the good still outweighs the bad by at least as far and wide a distance as that by which the Rangers once baked four and twenty Orioles in a 30-3 pie, in August 2007. It also says, as I’ve said often enough in these pages, that in baseball anything can happen—and usually does.