When all was said and finally done, Marvin Miller got what he no longer wanted. He’d said it expressly and pointedly enough, citing specifically the assorted Veterans Committees he believed with certain merit were often enough stacked for certain results. “At the age of 91,” he said, “I can do without farce.”

When all was said and finally done, Marvin Miller got what he no longer wanted. He’d said it expressly and pointedly enough, citing specifically the assorted Veterans Committees he believed with certain merit were often enough stacked for certain results. “At the age of 91,” he said, “I can do without farce.”

Miller’s name turned up on the Modern Era Committee ballot now concluded, and there emerged a bristling debate as to whether Miller’s express wishes did or didn’t supercede the prospect that, at long enough last, he would attain even posthumously the honour many believed too long overdue but his family believed should be set aside according to his very own wishes.

More than most baseball men Miller knew that the Rolling Stones were right about one thing at least, namely that you can’t always get what you want, but if you try sometimes, you just might find you get what you need. What he needed from this year’s Modern Era Committee to go into the Hall of Fame was twelve votes, and he got them, one shy of the thirteen awarded to enshrine former catcher Ted Simmons.

Wherever he reposes in the Elysian Fields now, Miller didn’t get what he wanted but got what he needed, and it’s to lament that previous Veterans Committees or their 21st Century successors-by-category didn’t give it to him while he was still alive and well enough to accept and appreciate it. But there’s a nice synergy in Miller going in however posthumously with Simmons who is very much alive, well, and working as an Atlanta Braves scout today.

Even as Curt Flood’s reserve clause challenge awaited its day before the Supreme Court, Simmons himself came close enough to challenging the clause himself, entering his second year as the St. Louis Cardinals’ regular catcher, who thought establishing himself thus even at age 22 was worthy of just a little bit more than a $6,000 or thereabout pay raise.

Simmons refused to sign for 1972 for a penny less than $30,000. The Cardinals’ general manager, Bing Devine, said not so fast, son, and held in the lowest $20,000s. Simmons opened the season without a contract, the Cardinals renewed him automatically as the rules of the time allowed, and everyone in baseball cast their jeweler’s eyes upon the sophomore catcher who defied the athletic stereotype (among other things, he’d serve time on the board of a St. Louis art museum and a knowledgeable one at that) and the clause that owners abused for generations to bind their players like chattel until they damn well felt like trading, selling, or releasing them.

This wasn’t a veteran who’d seen too much and heard too much more; this was a kid whom you might have thought had everything to lose but who lived as though principle trumped even a three-run homer. He played onward and refused any Cardinals entreaty that didn’t equal a $30,000 salary, then went to Atlanta the selected All-Star choice as the National League’s backup catcher. He’d barely landed and checked in when Devine rang the phone. Would Simmons kindly accept $75,000; or, the $30,000 he asked for for 1972 and $45,000 for 1973?

Miller watched Simmons very nervously, knowing the kid pondered taking it to court if things came that way, never mind that Flood had yet to get his Supreme Court ruling. (And lost, alas.) He understood completely when Simmons accepted Devine’s new proposal, but the Simmons case handed Miller intelligence you couldn’t buy on the black market or otherwise: the owners would rather hand a lad $75,000 than let any arbitrator get to within ten nautical miles of the reserve clause.

A former United Steelworkers of America economist, Miller won skeptical players over in the first place by being just who he was, and he wasn’t the stereotypical union man with a bludgeon instead of a brain, pressing hardest on the point that no concern of theirs was out of bounds and that the doors to the Players Association’s office would remain open whenever they wanted. His mantra was, “It’s your union,” a mantra one wishes was that of numerous other American labour unions to whom the rank and file were and often still are, generally, to be seen and not heard.

Ahead of the Simmons issue still lay Hall of Fame pitcher Catfish Hunter to shine a light on what a fair, open market portended for baseball players, when Oakland Athletics owner Charlie Finley reneged on insurance payments mandated in Hunter’s contract, and an arbitrator hearing Hunter’s grievance ruled in favour of the righthander. At once, Hunter’s Hertford, North Carolina home hamlet became baseball’s hottest address, teams swooping in prepared to offer him the moon, the stars, safe passage through the Klingon Empire, and grazing rights on the planets of his choice.

Hunter merely astonished one and all by finally signing the third-richest offer in front of him, at seven figures plus for the next five seasons, and one that came at almost the eleventh minute, because the Yankees—whose representative Clyde Kluttz went back with Hunter his entire career to that point—were willing to divide the dollars according to his wishes, right down to an annuity to guarantee his children’s education. After writing the division on a napkin in a diner nook, Hunter’s first question ahead of the dollars to be done was whether the Yankees could or would do that. They could. They did.

And ahead of that, still, lay Andy Messersmith, one of the game’s best pitchers, pitching for and haggling contract with the Los Angeles Dodgers in spring 1975. When those hagglings turned a little too personal for Messersmith’s taste, thanks to general manager Al Campanis injecting personal and not baseball issues and stinging the pitcher to his soul (and to this day he refuses to discuss it), Messersmith refused to talk to any executive lower than heir apparent Peter O’Malley and demanded a no-trade clause in the contract to come.

Like Simmons, Messersmith refused to sign unless he got the clause, out of refusing now to let the Al Campanises dictate his future if he could help it. Like Simmons, Messersmith played on in 1975, pitching well enough that when fans and artery-hardened sportswriters weren’t needling him about his unsigned contract the Dodgers were trying to fatten his calf in dollar terms. They offered him princely six-figure annual salaries at three years, but they refused to capitulate on the no-trade clause.

“I never went into this for the glory and betterment of the Players Association,” Messersmith, ordinarily what John Helyar (in The Lords of the Realm) described as happy-go-lucky and a little flaky, said much later. “At the start it was all personal. Al Campanis had stirred my anger, and it became a pride issue. When I get stubborn, I get very stubborn.” Indeed not until August 1975 did Miller reach out to the still-unsigned Messersmith, the last man standing among six players who opened 1975 without signed contracts. Only then did Messersmith agree to file a grievance seeking free agency if he finished the season unsigned.

Messersmith followed through. (Retiring pitcher Dave McNally, technically unsigned but intending to stay retired, agreed to join the grievance as insurance in case the Dodgers’ dollars seduced Messersmith, who wouldn’t be seduced.) The owners refused to listen when such representatives of their own as their Player Relations Committee leader (and then-Milwaukee Brewers chairman) Ed Fitzgerald, pleaded with them to consider negotiating a revision of the reserve system. “We need to negotiate while we’re in a power position,” he pleaded. Plea denied with the very pronounced sound of a gunshot’s bullet going through the owners’ feet.

And—abetted among other evidence by a newspaper article, in which no less than Minnesota Twins owner Calvin Griffith acknowledged a proper reserve clause application would make a player a free agent after one signed season and one option season, properly applied—arbitrator Peter Seitz ruled in Messersmith’s favour. “Curt Flood stood up for us,” Simmons would say. (Helyar described him as choked up.) “[Catfish] Hunter showed us what was out there. Andy showed us the way. Andy made it happen for us all.”

Miller was smart enough not to demand immediate free agency for all, recognising as he did that teams did have certain rights in players they developed even as he knew, and insisted, that baseball players should have the same rights as any other American from the greenest labourer to the most seasoned executive to test themselves on a fair, open job market when they were no longer under contract.

It did more for the good of the game than the artery-hardened hysterics of the day would have allowed, especially in their lamentations over the coming death of competitive balance. (Pace Mark Twain, the reports of its death were extremely exaggerated, and still are: among other things, more teams have won World Series since the Messersmith ruling than won the Series before it.) But few things were more astonishing than the owners’ subsequent chicaneries, unless it was seeing the years go passing by with the idea of Miller in the Hall of Fame not as popular with many of his former clients as his work on their behalf.

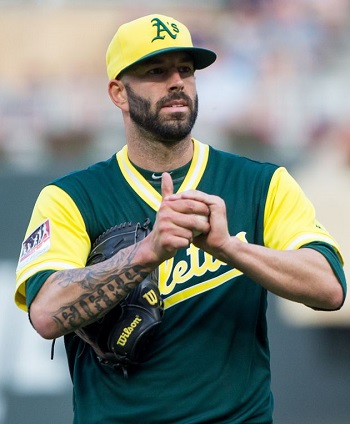

Simmons, of course, went forward to enjoy a career that should have gotten him elected to Cooperstown; his peak value matches that of the average Hall of Fame catcher. He went one and done in his only year’s eligibility on the Baseball Writers’ Association of America ballot. Exactly why never seemed clear, other than perhaps residual ill will over Simmons’s late-career tangle with Whitey Herzog (who traded him to the Brewers citing defensive shortcomings, after he declined repositioning the field), but the advanced metrics show Simmons the tenth best catcher to strap it on, ever. Maybe they had a problem marrying baseball’s most honorific museum to an art museum board director.