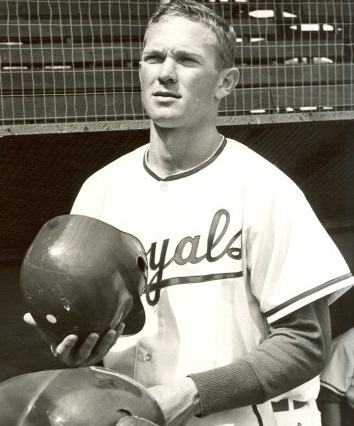

Roger Angell, accepting his J. G. Taylor Spink Award at the Hall of Fame in 2014.

Nine days before Eddie Cicotte confessed his membership in the Black Sox, the literary-minded wife of a New York attorney bore a son. Mother and son would each have a long term impact on The New Yorker; the son would have a concurrent and more enduring impact on baseball.

Katharine Sergeant Angell was five years from becoming The New Yorker‘s fiction editor and nine from divorcing her first husband and marrying a writer she’d previously recommended The New Yorker‘s legendary mastermind Harold Ross hire, E.B. White. Her son would assume her job in due course. While he was at it, he’d become baseball’s prose poet laureate.

Just don’t say that to Roger Angell if you should have the honour of meeting him, never mind wishing him a happy 99th birthday in person today.

“I’ve been accused once in a while of being a poet laureate, which has always sort of pissed me off,” Angell once told Salon writer Steve Kettman, coincidentally the author of the splendid One Day at Fenway and editor of Angell’s own anthology Game Time. “That’s not what I was trying to do. I think people who said that really haven’t read me, because what I’ve been doing a lot of times is reporting. It’s not exactly like everybody else’s reporting. I’m reporting about myself, as a fan as well as a baseball writer.”

Just like any average everyday American literary editor who goes to spring training, assorted ballparks, or the World Series, intending nothing but spot reporting, delivering observations the rest of us can only fantasise about delivering. Consider what he delivered in “The Web of the Game” (1981), after watching Ron Darling (then pitching for Yale University) and Frank Viola (then pitching for St. John’s University) tangled in Darling’s 11 no-hit innings, in a game during the 1981 players’ strike, with Smokey Joe Wood (a 34-5/1.91 ERA pitcher for the 1912 Red Sox, then 91 himself) in the audience and, coincidentally, as Angell’s seat companion:

The two pitchers held us — each as intent and calm and purposeful as the other. Ron Darling, never deviating from the purity of his stylish body-lean and leg-crook and his riding, down-thrusting delivery, poured fastballs through the diminishing daylight . . . Viola was dominant in his own fashion, also setting down the Yale hitters one, two, three in the ninth and 10th, with a handful of pitches. His rhythm — the constant variety of speeds and location on his pitches—had the enemy batters leaning and swaying with his motion, and, as antistrophic, was almost as exciting to watch as Darling’s flair and flame.

With two out in the top of the 11th, a St. John’s batter nudged a soft little roller up the first base line—such an easy, waiting, schoolboy sort of chance that the Yale first baseman, O’Connor, allowed the ball to carom off his mitt: a miserable little butchery, except that the second baseman, seeing his pitcher sprinting for the bag, now snatched up the ball and flipped it toward him almost despairingly. Darling took the toss while diving full-length at the bag and, rolling in the dirt, beat the runner by a hair.

“Oh, my!” said Joe Wood. “Oh, my, oh, my!”

A movement instigated by San Francisco Chronicle baseball writer Susan Slusser, which ought to have brought her a Pulitzer Prize for Distinguished Service on the spot, brought Angell his due (many thought overdue, including myself) in naming him the first non-daily beat writer to be elected to the Hall of Fame as its J.G. Taylor Spink award winner.

Daily beat writing has yielded its lyricists. Ring Lardner, Red Smith, Jim Murray (whose wit could have designated him baseball’s hybrid of Byron and James Thurber), Damon Runyon, Shirley Povich, Ira Berkow, to name a few who are very well anthologised and should not be absent from any serious fan and reader’s baseball libraries. Angell has been the thinking person’s epic observer and recorder of the thinking person’s epic game.

He has never been merely sound-bite quotable, which is his virtue and perhaps a key reason beyond his lack of employment by daily newspapers or Websites why it took as long as it did to bring him to Cooperstown as an honouree and not an observer. Which would you prefer—the customary clanking strain of sound-bite-angling, search-engine-optimising writing; or, something like this, concluding a remarkable study of the late and delightful relief pitcher Dan Quisenberry:

We want our favorites to be great out there, and when that stops we feel betrayed a little. They have not only failed but failed us. Maybe this is the real dividing line between pros and bystanders, between the players and the fans. All the players know that at any moment things can go horribly wrong for them in their line of work — they’ll stop hitting, or, if they’re pitchers, suddenly find that for some reason they can no longer fling the ball through that invisible sliver of air where it will do their best work for them — and they will have to live with that diminishment, that failure, for a time or even for good. It’s part of the game. They are prepared to lose out there in plain sight, while the rest of us do it in private and then pretend it hasn’t happened.

This stepson of one of America’s most treasured essayists, a New York Giants fan in his youth, knew how to appreciate the ties that bind baseball’s generations without caring to flog them with nostalgia’s buggy whip.

The stuff about the connection between baseball and American life, the Field of Dreams thing, gives me a pain. I hated that movie. It’s mostly fake. You look back into the meaning of old-time baseball, and really in the early days it was full of roughnecks and drunks. They beat up the umpires and played near saloons. In Field of Dreams there’s a line at the end that says the game of baseball was good when America was good, and they’re talking about the time of the biggest race riots in the country and Prohibition. What is that? That dreaminess, I really hated that.

He wasn’t quite prepared to acquit the contemporary game, its accoutrements in particular, either, as he made very clear writing around the turn of the current century: “The modern game is all bangs and effects: it’s summer-movie fare, awesome and forgettable—and extremely popular with the ticket-buyers.” He was thus kindred to the late commissioner A. Bartlett Giamatti, who lamented likewise the game’s embrace of theatrical ballpark gimmicks.

But Angell has also been an empath obeying particular boundaries of reason with assorted fans of assorted teams, even if his eye burrows deeper than theirs. Even among Red Sox fans in St. Louis watching generations of extraterrestrial deflation come to a surprising 2004 finish:

The Redbird collapse can probably be laid to weak pitching, unless you decide that the baseball gods, a little surfeited by the cruel jokes and disappointments they have inflicted on the Boston team and its followers down the years, and perhaps as sick of the Curse of the Bambino as the rest of us, decided to try a little tenderness.

This notion came to me in the sixth game of the scarifying American League Championship, when Gary Sheffield, swinging violently against Schilling with a teammate at first, topped a little nubber that rolled gently toward Sox third baseman Bill Mueller, then unexpectedly bumped into the bag and hopped up over his glove: base hit. Nothing ensued, as [Curt] Schilling quickly dismissed the next three Yankee hitters, but the tiny bank shot, which is not all that rare in the sport, was the sort of wrinkle that once could have invited a larger, grossly unfair complication and perhaps even a new vitrine next to [Bill] Buckner’s muff or [Aaron] Boone’s shot in the ghastly Sox gallery. You could almost envision the grin upstairs.

Instead, looking back at the action up till now — the Yankees’ daunting three-game lead after the first three meetings of this championship elimination; their nineteen runs in the Game Three blowout; and then the Sox’ two comeback wins achieved across the next two games or twenty-six innings or 10 hours and 51 minutes of consuming, astounding baseball—the old god feels an unfamiliar coal of pity within. “Ah, well,” he murmurs, turning away. “Let it go.”

Angell was never a member of the Baseball Writers Association of America. “The main requirement for membership,” says the BBWAA’s Website, “is still that a writer works for a newspaper or news outlet that covers major league baseball on a regular basis.” That may also be why it took so long to think of Angell as Hall of Fame material in consecrated fact as well as an article of faith. Working for a literary magazine instead of a sporting journal, too, allowed him a freedom of the soul most baseball writers don’t dare imagine.

Another legendary New Yorker editor, William Shawn, instigated Angell’s journey when sending him to spring training in 1962 with one instruction: “See what you find.” Little did Shawn know what he wreaked. Angell subsequently found the Original Mets and their equally surrealistic fans.

“[T]hat was very lucky for me when I thought it out,” Angell told Kettman. “It occurred to me fairly early on that nobody was writing about the fans. “I was a fan, and I felt more like a fan than a sportswriter. I spent a lot of time in the stands, and I was sort of nervous in the clubhouse or the press box. And that was a great fan story, the first year of the Mets. They were these terrific losers that New York took to its heart.”

He would go forth to write with comparable eloquence on such things as the dominance of Sandy Koufax; the miscomprehended “Distance” (his title) of Bob Gibson; the unfathomable collapse of Steve Blass (a Pirates pitching stalwart and World Series hero one moment, unable to reach the strike zone without disaster the next, so it seemed); the trans-dimensional 1975 World Series; the labor disputes in the free agency era; the pride of such men as Tom Seaver and Reggie Jackson; the foolishness of such men as Pete Rose; and the jagged contrast between two Bay Area owners, Charles Finley (Athletics) and Horace Stoneham (Giants):

Baseball as occasion — the enjoyment and company of the game — apparently means nothing to him. Finley is generally reputed to be without friends, and his treatment of his players has been characterized by habitual suspicion, truculence, inconsistency, public abasement, impatience, flattery, parsimony, and ingratitude. He also wins.

Horace Stoneham is — well, most of all he is not Charlie Finley … He is shy, self-effacing, and apparently incapable of public attitudinizing. He attends every home game but is seldom recognizable even by the hoariest Giants fans . . . In 1972, when his dwindling financial resources forced him at last to trade away Willie Mays, perhaps the greatest Giant of them all, he arranged a deal that permitted Mays to move along to the Mets with a salary and a subsequent retirement plan that would guarantee his comfort for the rest of his life…

. . . [W]hen I read that the San Francisco Giants were up for sale, it suddenly came to me that the baseball magnate I really wanted to spend an afternoon with was Horace Stoneham. I got on the telephone to some friends of mine and his (I had never met him), and explained that I did not want to discuss attendance figures or sales prices with him but just wanted to talk baseball. Stoneham called me back in less than an hour. “Come on out,” he said in a cheerful, gravelly Polo Grounds sort of voice. “Come out, and we’ll go to the game together.”

That was part of “The Companions of the Game,” published in The New Yorker in 1975 and republished in two subsequent Angell anthologies, Five Seasons and Game Time. Angell’s baseball anthologies have been subtitled, invariably, A Baseball Companion. He has been that through his reporting and writing, which has been in turn that and more to those who’ve had the pleasure and good taste to read it.

He accepted his Spink Award with grace at the Hall of Fame in July 2014, the kind that makes you think you’d love nothing better than to have him as your company at a game, any game, whether watching the Astros’, the Yankees’, the Dodgers’, the Braves’, the Twins’ dominance; whether agonising over the wrestling match between the Nationals, the Cubs, the Brewers, the Mets, and the Phillies for second place and thus the National League’s wild cards; or, whether suffering along with those unable to release the Orioles, the Tigers, the Mariners, the Marlins, or the Pirates from their hearts no matter how those teams have released competitive sense.

It’s not that life has been a ceaseless pleasure for him. He’s been widowed twice; his eldest daughter was a suicide at 62. He has written (and been honoured for, with the 2015 National Magazine Award for Essays and Criticism) of mortality with the same reality-tempered lyricism as he’s written about our game:

“Most of the people my age is dead. You could look it up” was the way Casey Stengel put it. He was seventy-five at the time, and contemporary social scientists might prefer Casey’s line delivered at eighty-five now, for accuracy, but the point remains. We geezers carry about a bulging directory of dead husbands or wives, children, parents, lovers, brothers and sisters, dentists and shrinks, office sidekicks, summer neighbors, classmates, and bosses, all once entirely familiar to us and seen as part of the safe landscape of the day. It’s no wonder we’re a bit bent. The surprise, for me, is that the accruing weight of these departures doesn’t bury us, and that even the pain of an almost unbearable loss gives way quite quickly to something more distant but still stubbornly gleaming. The dead have departed, but gestures and glances and tones of voice of theirs, even scraps of clothing—that pale-yellow Saks scarf—reappear unexpectedly, along with accompanying touches of sweetness or irritation.

That from the man who once wrote, “Since baseball time is measured only in outs, all you have to do is succeed utterly: keep hitting, keep the rally alive, and you have defeated time. You remain forever young.” And, sometimes, it takes nothing more than a leisurely walk with the bases loaded to keep a rally going, as happened to Pete Alonso Wednesday night, as the Mets opened up in the top of the ninth to overtake and beat the Rockies, 7-4.

Angell’s meditation on mortality is the title essay of his last known anthology, This Old Man: All in Pieces. A man who endures such slings and arrows with the same affectionate wit through which he endured the Original Mets, engaged the owner of the team that engaged his boyhood, or gazed with perspective upon the end of generations of surrealistic Red Sox calamity and the Astros’ first entry into the Promised Land, is a man about whom you can say safely that only the years he’s lived make him ancient.

One year shy of a centenarian, Angell on his birthday today is 144 years younger than his country—which should count its blessings in numerous ways, including that he still lives and writes among us—and he may be twice as wise, too. Happy birthday to the gentleman about whom I refuse to surrender my belief, based upon a lifetime in the company of his writing, that Peter Golenbock was wrong to call him baseball’s Homer—because Homer was ancient Greece’s Roger Angell.

(Portions of this essay were published previously.)

Forget the wild card races for a few moments. Have a good gander at the National League Central. Where the Cardinals and the Cubs entered Thursday’s play numeros uno and two-o in the division.

Forget the wild card races for a few moments. Have a good gander at the National League Central. Where the Cardinals and the Cubs entered Thursday’s play numeros uno and two-o in the division.