The myth: Candlestick cost Mays buckets of bombs. The truth: otherwise . . .

In 2008, Bob Costas gave Willie Mays and Henry Aaron an hour’s worth of a special joint interview on Costas’s HBO sports program, Costas Now. The mostly amiable discussion yielded only one moment of irritation from either Hall of Famer, when Costas mentioned Aaron hitting 95 more lifetime home runs than Mays hit.

For the only time during the discussion the Say Hey Kid became a little indignant. “But he had much better ballparks to hit ‘em in,” Mays complained. “I must have lost a hundred home runs to my ballparks, especially that wind at Candlestick.”

Alas, to this day you can still bump into fans who buy into Mays’s complaint, which predated by a few decades the Mays/Aaron sit-down with Costas. Just as you can still bump into fans who think selling Babe Ruth, and not incompetent administration plus surrealistic circumstances, turned the Red Sox into baseball’s haunted house for all those decades.

Candlestick Park, the Giants’ home from 1960-1999, was notorious for clashing winds, damp air and fog, and being a particularly chilly ballpark sooner down the stretch than most of the National League’s other parks. Giants players were hardly the only ones to find the joint less than appealing, though nobody noticed the Beatles complaining (even if their fans were heartsick) when they played their last-ever American concert there in 1966.

When Walter O’Malley began planning what became Dodger Stadium, legends include that he obtained a copy of the Candlestick Park blueprints and gave them to his architect with one instruction: “Study these and learn what not to do.” When the original open-back park was enclosed in 1970, the better to accommodate the NFL’s 49ers, it robbed Giant fans of one of their only Candlestick pleasures, a pleasant view of San Francisco Bay.

The Stick earned a few unflattering nicknames during its life—Windlestick, the Quagmire, and the Ashtray by the Bay (hardly as colourful as that attached to the Indians’ old Municipal Stadium: the Mistake on the Lake)—and at least one tragicomic one, when the Loma Prieta earthquake interrupted the 1989 World Series and several wags called the quake-shaking park Wiggly Field.

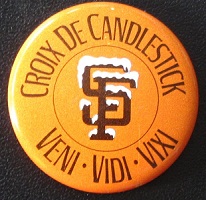

The park’s sour reputation metastasised enough that the Giants themselves finally took to trying to sell the flaws as perverse virtues. They awarded “Croix de Candlestick” pins to fans who went the distance for nighttime extra inning games. The round orange pins featured a frosted Giants cap logo in the center and, circling it, “Croix de Candlestick” at the top and, ad the bottom, Veni, Vidi, Vixi. (“I Came, I Saw, I Survived.”)

The park’s sour reputation metastasised enough that the Giants themselves finally took to trying to sell the flaws as perverse virtues. They awarded “Croix de Candlestick” pins to fans who went the distance for nighttime extra inning games. The round orange pins featured a frosted Giants cap logo in the center and, circling it, “Croix de Candlestick” at the top and, ad the bottom, Veni, Vidi, Vixi. (“I Came, I Saw, I Survived.”)

When the Giants began playing there in 1960, following two seasons in ancient little Seals Stadium, after their departure from New York, Willie Mays, too, came, saw, and survived. Rather admirably at that, when all was said and done.

The Hall of Famer played twelve major league seasons with Candlestick Park as his home ballpark and hit 202 of his 660 career home runs in the Stick. But to hear those admirers who continue lamenting he might have passed Babe Ruth on the all-time home run list first, you’d think before seeing the evidence that Mays as a San Francisco Giant couldn’t wait to get out of town at every last available moment.

You’d gotten the same impression from Mays himself, even before the Costas discussion, if you read such comments as these from the 1966 memoir (My Life In and Out of Baseball) he co-authored with Charles Einstein:

Hell, Candlestick was too big. First day I ever came to bat there, in hitting practice the day before the ’60 season opened, it was windy and raw, and whoever was pitching threw me a fat slider and I swung and looked and I was holding just the thin handle of the bat in my hand. The ball had sawed my bat in two!

Oho, but right after that Mays said this:

They made changes the following year, bringing the fences in and putting up a green backdrop behind center field so the hitters could see the ball better, which was important because the Giants play more day games than any other team except the Cubs, who have no lights in their park.

When Candlestick opened for the 1960 season the fences were quite deep and challenging to even the most ballistic power hitters, and the Giants did bring the fences in a bit for 1961. Life got a little easier for Mays and the Giants’ other power hitters such as Hall of Famers Willie McCovey and Orlando Cepeda.

But maybe you’re still not convinced. You need evidence, which I’m more than happy to provide. Here is a table that tells you exactly how Willie Mays hit for power at home and on the road during the twelve seasons Candlestick was his home. The black ink shows when he was better at home:

| Mays in Candlestick Park | Mays On the Road | Road HR Diff | |||||||

| HR | OBP | SLG | OPS | HR | OBP | SLG | OPS | ||

| 1960 | 12 | .366 | .509 | .875 | 17 | .395 | .596 | .990 | +5 |

| 1961 | 21 | .384 | .582 | .965 | 19 | .402 | .586 | .988 | -2 |

| 1962 | 28 | .408 | .683 | 1.091 | 21 | .360 | .548 | .908 | -7 |

| 1963 | 20 | .398 | .622 | 1.021 | 18 | .363 | .545 | .908 | -2 |

| 1964 | 25 | .405 | .656 | 1.061 | 22 | .362 | .565 | .927 | -3 |

| 1965 | 24 | .400 | .640 | 1.040 | 28 | .396 | .650 | 1.046 | +4 |

| 1966 | 16 | .359 | .556 | .917 | 21 | .375 | .555 | .929 | +5 |

| 1967 | 13 | .331 | .472 | .803 | 9 | .337 | .435 | .772 | -4 |

| 1968 | 12 | .370 | .496 | .865 | 11 | .374 | .480 | .854 | -1 |

| 1969 | 7 | .361 | .432 | .793 | 6 | .362 | .441 | .802 | -1 |

| 1970 | 15 | .393 | .518 | .911 | 13 | .388 | .496 | .884 | -2 |

| 1971 | 9 | .453 | .518 | .971 | 9 | .401 | .451 | .852 | — |

| TOTAL | 202 | 194 | |||||||

| SEASON AVG. | 17 | 16 | |||||||

Mays was better on the road than at home in 1960, but then came the fence change at the Stick. And for the eleven seasons to follow, Mays was a little more powerful at the Stick eight times and dead even between home and the road once. Not to mention that, cumulatively, he hit eight more home runs at the Stick than he hit on the road when the Stick was home.

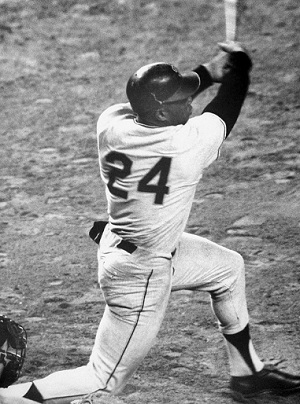

Mays, hitting the 500th of his 660 career home runs. He hit it in one of the National League’s actual worst hitting parks, too—the Astrodome.

Willie also had a better on-base percentage at home in half his Candlestick seasons and a better home slugging percentage eight times. Seven times his OPS (on base percentage plus slugging percentage) was better at the Stick. Not to mention that he achieved a 1.000+ OPS four times at the Stick . . . but only once on the road in the same seasons.

Go ahead, ask: If Candlestick Park really didn’t keep Willie Mays’s home run power that heavily in check no matter how insane its climate conditions, what really kept him from beating Henry Aaron to Babe Ruth’s punch?

As Groucho Marx once said, it’s so simple that a child of five could understand it—now, somebody send for a child of five. Well, I don’t have a child of five (my son is 25), so you’ll have to settle for me. But it is that simple: the Army. And, the Polo Grounds.

Mays won the National League’s Rookie of the Year award in 1951, and he got to play only 34 games in 1952 when he was inducted into the Army at age 21. He missed the rest of the 1952 season and the whole of the 1953 season. It’s not unreasonable to suggest that his Army service cost Mays 60+ home runs, which would have been enough to put him past Ruth first.

But I think I know what you’re thinking if you remember the place: The Polo Grounds? With those yummy short foul lines? So let’s have a look at Mays the New York Giant, leaving out his aborted 1952 season, with the black ink showing likewise where he was better at home:

| Mays In the Polo Grounds | Mays On the Road | Road HR Diff | |||||||

| HR | OBP | SLG | OPS | HR | OBP | SLG | OPS | ||

| 1951 | 13 | .344 | .535 | .879 | 7 | .364 | .410 | .774 | -6 |

| 1954 | 20 | .344 | .645 | 1.059 | 21 | .410 | .689 | 1.099 | +1 |

| 1955 | 22 | .405 | .648 | 1.053 | 29 | .395 | .670 | 1.065 | +7 |

| 1956 | 20 | .358 | .592 | .950 | 16 | .381 | .524 | .905 | -4 |

| 1957 | 17 | .424 | .624 | 1.047 | 18 | .393 | .627 | 1.020 | -1 |

| TOTAL | 92 | 91 | |||||||

| AVG. | 18 | 18 | |||||||

In five full seasons with the Polo Grounds as home, Willie Mays hit more home runs on the road in two of the five; he slugged better at home twice and reached base more often at home twice. Yet he hit exactly one more home run in the Polo Grounds than he hit on the road over that entire span, and averaged the same number of bombs at home and on the road give or take a fractional point or two. That’s against hitting eight more in Candlestick Park than on the road during his Stick seasons.

Don’t be surprised that Mays was that close whether at home or on the road in either ballpark; he was virtually the same player on the road as he was at home lifetime. He hit ten more home runs at home; he batted one point higher at home; his on-base percentage was only five points higher at home. Willie Mays didn’t need the home field advantage.

Return for a moment to the season Candlestick opened. The winds weren’t the park’s only issue. Dead center field was 420 feet from the plate; the power alleys in right- and left-center field were 397 feet each; the foul lines were 330 feet (left field) and 335 feet (right field) from home, respectively. Tell me you can’t picture a lot of long fly outs to left- and right-center fields.

That wasn’t exactly a cozy confine for a power hitter. But for 1961 the Giants cut the fences slightly. The foul lines remained the same, but now left center field was 365 feet from the plate, right center field was 375 feet from the plate, and dead center field was 410 feet. And Mays hit nine more homers in the Stick in 1961 than he hit in 1960.

Do you really know or really remember the Polo Grounds? I do both, since I saw the place as a child in 1962 when the Original Mets played there their first two seasons awaiting Shea Stadium’s completion. (I still can’t get over the manner in which the box seats were sectioned—by dangling chains instead of bars.) First, have a look for yourself:

You’re not seeing things. The foul lines were 279 feet from the plate in left field and 258 feet from the plate in right. Left center field was 450 feet from the plate and right center field, 449 feet. Dead center field—extending out between the bleachers and beneath the elevated structure housing the team offices and the clubhouses—was 483 feet. We’re talking about a field that must have looked like the deepest fences moved a little further away every time you checked in at the plate.

(Among other things, now do you get what was so spectacular about Mays’s legendary running catch on the track and throw in off Vic Wertz’s long fly in Game One of the 1954 World Series?)

Willie Mays was most likely kept from passing Babe Ruth first on the all-time career home run list because of both his Army service and playing in the challenge of the Polo Grounds before he ever hit San Francisco. The Polo Grounds didn’t stop him from becoming Willie Mays, of course, but I think the hard evidence says the park didn’t exactly do him that many favours when it came to hitting for distance, either.

San Francisco wasn’t exactly friendly to Mays in his first few years there, either. All the notice he earned in New York with his play and exploits got a chilly reception by the Bay, where Mays himself phrased it best, while remembering how Mickey Mantle got booed in Yankee Stadium: “It wasn’t so much what we were. It was more what we weren’t. Neither one of us was Joe DiMaggio.”

The Giants played two seasons in Seals Stadium, where DiMaggio once shone in center field in the ancient, tough Pacific Coast League, and the memories of DiMaggio before he became the Yankee Clipper remained powerful, especially since DiMaggio was native to the Bay Area and lived there many years after his career ended. No one playing in San Francisco in those years could avoid DiMaggio comparisons.*

Not even Willie Mays. That, plus surprising racial issues such as difficulty finding a renter or realtor who would rent or sell to a black couple (Mays was married to his first wife at the time; the marriage collapsed under her extravagance plunging Mays into debt), and his own manager’s hyperbole (Bill Rigney rashly predicted Mays would break Ruth’s single season home run record), meant Mays playing under pressure he hadn’t experienced since he was a nervous New York rookie.

Perhaps roaming center field and swinging at the plate, Stick or no Stick, provided the best sanctuary from the pressures he felt off the field. After the Giants knocked the Dodgers out of a pennant in a three-game playoff in 1962, that’s when San Francisco began to warm up to Mays even if its ballpark wasn’t warm and too cozy.

But we shouldn’t forget the third reason he couldn’t pass Ruth’s career mark first: age.

Mays’s last truly great season was 1966—when he was 35 years old. Henry Aaron was three years younger. And, also in 1966, the Braves moved to Atlanta and into Fulton County Stadium. Also known as the Launching Pad. Aaron moved from a home park that challenged him to a park that was even better for him than Candlestick Park, for all the kvetching, was for Mays. That was the first time in his career that Aaron got to play his home games in a park like that—after he’d been in the league for twelve seasons.

Mays finished third in the National League’s Most Valuable Player award voting in 1966 and was worth 9.0 wins above a replacement-level player, better than two over his career average and above the minimum that would indicate an MVP-worthy season. He hit his decline phase the following season and stayed there, little by little, heartbreakingly to those who saw him at his peaks, over his final five seasons in the Stick, before he was dealt to the Mets to finish his career in the city that first embraced and loved him.

Aaron, too, was practically the same player on the road as he was at home lifetime. He hit fifteen more homers at home; he batted three points lower; his on-base percentage was ten points higher. And his slugging percentage was five points higher at home. Mays’s lifetime slugging percentage was eighteen points higher at home lifetime.

It’s too easy to understand why Candlestick Park wasn’t even close to being number one on any player’s or fan’s hit parade for baseball conditions. It’s just as easy to look at that pesky evidence. It’s not Mays’s fault or anyone else’s if people choose to continue letting the evidence get in the way of a fun or funny legend.

But if you do look, you should see that while he may have despised the joint, and had problems not of his own making off the field in San Francisco that he didn’t always have in New York, the Stick didn’t hurt Willie Mays anywhere near the extent to which he and his legions of admirers—one of whom will always be yours truly—have believed too long.

And, perhaps pending the final outcome of Mike Trout’s career, Mays and his old New York buddy/rival Mickey Mantle may still be the two best who ever played the game.

* Speaking of Joe DiMaggio: The myth also persists that Yankee Stadium “cost” DiMaggio a bucket or three of home runs. He did have a problem hitting righthanded into that deep-as-the-ocean left center field . . . but he also refused to even think about hitting any other way.

You want to kvetch about today’s pull-happy bombardiers who won’t hit the other way, especially to beat those pesky overshifts? Guess what DiMaggio said when someone suggested he try hitting toward Yankee Stadium’s fabled short right field porch when the occasions arose: I could p@ss those over that wall. That’s not hitting. Well, now.