It was once to wonder how it would have looked if 6’8″ J.R. Richard could have pitched to 6’8″ Frank Howard.

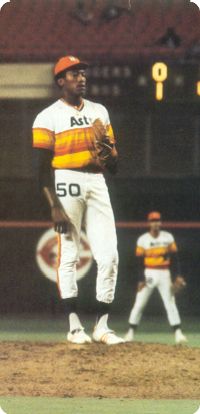

A 69th birthday isn’t one of the classic milestone birthdays men and women commemorate, but J.R. Richard—who turned 69 today—isn’t an ordinary 69-year-old. He’s been to the top of the mountain and the to the absolute depth of the deepest valley. And back. “(I)f you beat me I’m gonna die trying,” Richard said in 2012, remembering the attitude he took to the mound. “I was willing to give my life for it.”

He damn near did give his life for it.

The stroke Richard suffered while on the disabled list not long after the 1980 All-Star Game he’d started embarrassed everyone around the Astros, team and press alike, who’d speculated the giant righthander was dogging things. Though many of those doubting writers and broadcasters apologised publicly in the wake of the stroke, it couldn’t help him.

Once one of the two most famous Texas-based men going by his initials, Richard only seemed like a fictional character. J.R. Ewing was a larger-than-life television rogue who wasn’t above practically anything short of murder to get his way. J.R. Richard looked larger than life on the mound in an Astros uniform, threw like it, and sometimes—though not always comfortably—acted like it.

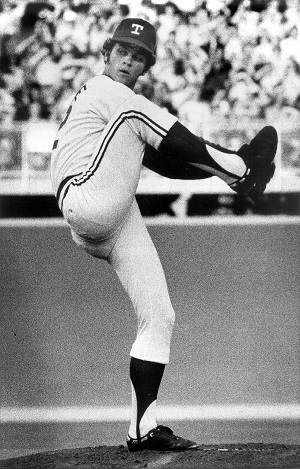

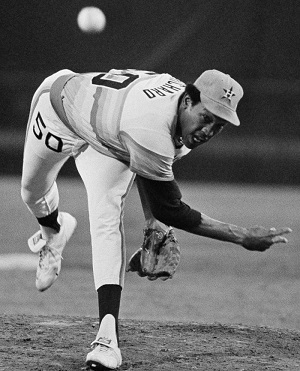

He stood 6’8″ on the mound in a well tapered body and, between pitches, he looked a little like the big shy kid barely aware that the cute girl he crushed on was praying just as hard that he’d ask her to dance as he prayed for the courage to ask.

Then Richard went into his no-windup motion, his high knee-bent kick, and delivered. In that delivery, with his large hand almost covering the ball whole before he threw, the big shy kid turned into a behemoth who looked as though he’d crack your bat in half between two fingers if he wasn’t in the mood to throw you something one blink would make you wonder if it really came your way.

It was enough to make you wonder how it would have looked if Richard could ever have pitched to 6’8″ Frank Howard, who didn’t play in the same circuit. The sight of Richard, looking like he’d piledrive you through the batter’s box, pitching to Howard, who looked like he’d carve his initials into your forehead if he didn’t hit one over the county line? Chuck Jones himself couldn’t design a better baseball exaggeration.

Richard in prime time . . .

The closest Richard ever got to that was facing 6’6″ Dave Kingman 33 times. The bad news for Richard: Kingman did hit one out off him. The bad news for Kingman: Richard otherwise kept him to a pair of doubles and a pair of walks while striking him out fourteen times and holding him to a .226/.273/.387 slash line.

And if Kingman hadn’t been disabled with a case of appendicitis, Richard would have had to deal with him in his first major league start, 5 September 1971. The start in which Richard tied the major league record for pitchers in their first games with fifteen strikeouts. (He joined Brooklyn Dodger blink-of-a-eye legend Karl Spooner.) The start in which he struck no less than Willie Mays out in the first, third, and fifth innings.

Maybe the strangest game of Richard’s career was 19 September 1978, against the Braves. He faced off against ancient, one-time Astro Jim Bouton, trying a major league comeback and getting his shot with the Braves that month. Bouton must have thought it was the Braves asking David to bring Goliath down without a slingshot. “The young flamethrower and the old junkballer,” Bouton would remember.

Richard spent his seven innings breaking Hall of Famer Tom Seaver’s record for single-season strikeouts by a righthander, the money punchout coming at Bob Horner’s expense, while surrendering two earned runs on three hits and three walks. Bouton spent his seven innings surrendering two earned runs on five hits, striking out one, and walking five. David and Goliath fought to a draw that night.

The Braves would win it after Horner doubled home pinch runner Barry Bonnell in the top of the ninth off Joaquin Andujar but the Astros couldn’t muster more than a strikeout, a ground out, and a fly out against Gene Garber, the Braves reliever who’d also stopped Pete Rose’s 44-game hitting streak.

It took Richard a few seasons of inconsistency, periodic wildness, and a few injuries, before he took complete command of his howitzer fastball and his wide-moving slider and became a full-time National League terror. He was sometimes forbidding and sometimes playful; he spoke in the low drawl of the Louisiana fisherman he loved being off duty and off-season.

Rotation mates in 1980 before the stroke. Nolan Ryan looks like he doesn’t trust what might be behind Richard’s sneaky-looking grin.

He posted back-to-back 300+ strikeout seasons in 1978 and 1979 (his 313 in ’79 remain the Astros’ single-season strikeout record); he started the 1980 All-Star Game. He finished fourth in the National League’s Cy Young Award voting in 1978 and third in 1979, and he probably should have won the 1979 award: he led the league in strikeout-to-walk rate and the entire Show in strikeouts per nine, lowest hits per nine (and believe it or not he’s still fifth on the all-time list), ERA (2.71) and fielding-independent pitching. (Again: your ERA when the defense behind you is removed from the figuring: 2.21.)

Nobody including Richard himself knows whether his periodic, recreational cocaine indulgence played any role in what happened to him in 1980. He complained of shoulder fatigue well before that 1980 All-Star Game; a small reputation for moodiness led too many to think the behemoth was simply whining when he complained his shoulder and forearm felt fatigued. Some of those dismissals were racist; others, merely ignorant.

Doctors found obstructions in his arm and neck arteries but decided they weren’t serious enough for surgical correction. Then came 30 July 1980, when Richard—staying behind while the team hit the road—had a little workout on an Astrodome sideline. “I would hear a lot of high-pitched ringing in my left ear, which I didn’t think nothing about it at that time,” he remembered to WBUR’s Bill Littlefield in 2015.

I kind of just shook it off and kept on throwing a few more. Then I threw a couple more, then I became real nauseated, and I lay down on the Astrodome floor. And the next thing I remember I was waking up in the hospital. I had been complaining to the Astros for almost a month or two about something was wrong. And if I’m such a valuable asset to the ball club, why wasn’t I immediately rushed to the doctors from Chicago when it first started? Again, if I was such a valuable asset to the company?

Stroke. As it turned out, a subsequent CAT scan showed three separate strokes and a presence of thoracic outlet syndrome that left him with an artery pinch while he pitched. (Richard has said he was also told his shoulder muscles were overdeveloped enough to contribute to the problem.) Small wonder he looked less than himself starting that All-Star Game despite three strikeouts and no runs in his two innings’ work.

Career over, despite a comeback attempt or two to come, during one of which Thomas Boswell observed, “Richard is more pleasant, more outgoing, more generous with other people than ever before in his life. Once he was the most forbidding Astro. Now he may be the least, signing autographs and seeking out chitchat. After a lifetime as the Goliath overdog, he is now everybody’s underdog, and he enjoys it. Richard may even have become the symbol of a decent, long-out-of-fashion idea: mutual tolerance.”

“(W)hen people don’t understand who you are, when people can’t control you, they have a tendency to want to destroy you,” Richard told Littlefield, who interviewed him on the publication of his memoir, Still Throwing Heat: Strikeouts, the Streets, and a Second Chance. “But see, you got to realize this: Sports is a business. Nothing more or nothing less.”

A year before he was felled, Richard signed a four-year contract at $3.2 million. When the Astros and Richard said goodbye for keeps in 1984, he returned to his native Louisiana, spent a lot of time between there and Galveston, Texas fishing as if it was going out of style (as he still loves to do when possible), wringing baseball out of his system, winning a $1.2 million malpractise action against the Astros’ medical staff, and working selling cars and recreational vehicles for a time.

Unlike his television namesake, though, this J.R. wasn’t exactly made for the oil business: he lost $300,000 in an oil investment scam. Then, he lost another $669,000 in his first divorce. Further business problems and a second marital failure wiped him out completely, costing him his home and finally leaving him living under that Houston bridge.

Richard and his wife, Lula: “She helped with a lot of stability, in every way.”

Until a couple of former Astros teammates including Jimmy Wynn called another ex-teammate, Bob Watson, then the Astros’ general manager, around 1994. They plus the Baseball Assistance Team helped Richard start back to his feet. His minister, Rev. Floyd Lewis, helped him stay there. Most of all, Richard helped himself, largely by abandoning his admitted one-time bull-headedness and letting God take his hand and his spirit.

Richard has long since become a minister at Mt. Pleasant Church, while working with Houston donors to set up children’s baseball programs where he teaches assorted children the game and other hard-learned lessons. He also tries through his faith and his efforts to help the homeless help themselves.

“They’ve got to have a different mindset,” Richard told Littlefield. “You see a man could eat a whole whale, but it takes one bite at a time. Or he can walk a mile, but it takes one step at a time. So if you’re willing to take that step, [God] will make a way out of no way. See, God is the only one I know who can take a mess, go in a mess, clean up a mess and come back out and don’t be messy. Now you figure that out.”

He has even remarried happily. He met his third wife while sharing a bus on a church trip and she was recently widowed; he wrote his phone number inside the cover of her Bible. Their first date was a steak dinner. After they “courted” two years, as he put it in Still Throwing Heat, they married in 2010.

The righthander one writer once described as looking as though he could just reach to shake your hand from the mound before striking you out throws a far different pitch now. And the Astros will induct him into the team’s Hall of Fame come 3 August. Perhaps they’ll surprise the pitcher a former team leadership once doubted gravely enough by finally retiring his uniform number (50), something he admits he’d love dearly.

He hasn’t lost his laconic wit. When fans meet him and remember their shock over his stroke, he’s liable to reply with that half-mischievous grin, “I couldn’t believe it, either.”

Richard still has pride enough in what he did as a pitcher. Now and then, half puckish and half dead serious, he calls himself the only man in the world who could throw a baseball through a car wash and never get the ball wet. It’s not necessarily that much an exaggeration for a pitcher whose fastball often topped out at 100 mph.

But it’s not as important as the comeback he finally made after he got knocked down several times over. From survivor to thriver.