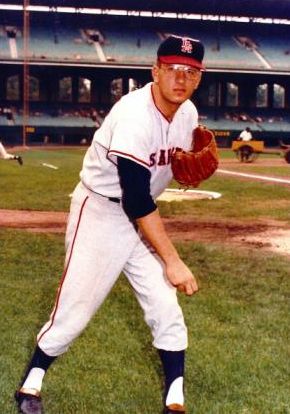

Eli Grba, the first Angel . . . (Photo courtesy of the Society for American Baseball Research.)

No less than Casey Stengel himself suggested the newborn major league Los Angeles Angels help themselves when the Yankees made Eli Grba available in baseball’s first expansion draft. Stengel liked the bespectacled righthander’s potential even if, in his final seasons managing the team, he couldn’t always swing Grba into the Yankee rotation, and Grba’s record to date mixed between starting and the bullpen was inconsistent.

The National League expanded a year later, with Stengel on tap as the manager of the incoming Mets, and with the first pick of that expansion draft the Mets picked Giants catcher Hobie Landrith. “You hafta have a catcher,” Stengel said of the pick, “or else you’ll have a lot of passed balls.” So the Ol’ Perfesser had a hand in a battery being picked to open each league’s first expansions.

Grba, who died at 84 Monday following a three-month battle with pancreatic cancer, started and won the Angels’ first regular season game, a 7-2 complete-game triumph over the Baltimore Orioles. The game featured future Hall of Famers Brooks Robinson and Hoyt Wilhelm and the Angels drawing first blood with back-to-back home runs from Ted Kluszewski (drafted from the White Sox) and Bob Cerv (drafted like Grba from the Yankees) in the top of the first off Orioles starter Milt Pappas.

The Angels weren’t even close to finished. They battered Pappas and his relief John Papa before Wes Stock, Billy Hoeft, and Wilhelm settled them down, including an RBI single from pint-sized outfielder Albie Pearson (a draft from the Orioles) and a three-run homer from Kluszewski in the second, putting them up 7-0. (Kluszewski and Pearson roomed on the road, with the 6’2″ muscular Kluszewski telling the 5’5″ Pearson, “I get the bed and you get the dresser drawer.”)

The only runs the Orioles could pry out of Grba that day were Jim Gentile scoring on a fielding and throwing error on the same two-out infield play in the second, and Jackie Brandt scoring on an infield error in the third.

Grba, who’d won six of ten decisions with the 1960 Yankees, finished a six-hitter and provided immediate fodder for headline writers who couldn’t resist having mad fun with his missing-vowel surname (pronounced like the baby food brand) in the times to come. (GRBA PTCHS 4-HTTR was typical.) The bad news was that his triumph was the only win on a 1-7 existence-opening Angels road trip that was further compromised by eight rainouts. It took the 1962 Mets losing the first nine straight of their existence a year later to erase that, sort of.

A big righthander himself, Grba would stand after the Angels’ first two seasons as their all-time winner (19) and all-time loser (22). The further bad news was that in 1962 he’d be lost in the glittery shuffle of rookies Bo Belinsky and Dean Chance—both of whom took a little too readily to the lifestyle of the Hollywood demimonde, Belinsky especially, and both of whom led the pitching staff much of the season while they were at it, sparking the outside possibility of the Angels reaching the World Series.

It didn’t happen. Belinsky opened the season 7-1—including five straight wins to open with the fifth being his once-fabled no-hitter—but finished 10-11 with a 3.56 ERA. Chance led the starters with 14 wins and a 2.96 ERA. Grba found himself back in the same pattern he’d experienced with the Yankees, shuttling between starting and relieving, and finished with eight wins, nine losses, and a 4.54 ERA despite the advent of a pitching-rich baseball era and the Angels playing their home games in Dodger Stadium. (The Angels weren’t exactly buddies with the Dodgers, so much not that their broadcasters called the park Chavez Ravine at owner Gene Autry’s insistence.)

The Angels finished third in the American League in 1962, still a staggering season for an expansion team. They were hit even harder when 40-year-old reliever Art Fowler took a line drive in his face during pre-game practise and starter Ken McBride went down with a cracked rib, and a six-game losing streak in September erased their faint pennant hope.

An only child whose mother raised him alone in Chicago after his father abandoned her when their son was still a small boy, Grba was first a Red Sox discovery until they dealt him to the Yankees in March 1957. The kid who’d grown up a White Sox fan was less than thrilled: “The Yankees would come in and beat us all the time.” His Yankee spell was delayed when the Army drafted him; he was discharged in time for spring training 1959.

To hell and back, Grba tosses out a gold-covered baseball as a ceremonial first pitch for the Angels’ fiftieth Opening Day.

Grba was the Angels’ starting pitcher on Opening Day their first two seasons. In May 1963, after marrying and buying his home, Grba was sent to the minors. “I don’t understand,” he’d say, “how a guy can be good enough to pitch the opening game two years in a row and then isn’t even good enough to pitch in the bullpen.” They sent him to Honolulu, the same minor league team where they exiled Belinsky after a terrible 1963 start.

That was after the Angels unloaded another former Yankee, former relief star Ryne Duren, after Duren’s already hard drinking began to spiral out of control when his marriage collapsed and his infant son unexpectedly died. Duren would drink himself out of baseball (as a Senator, he once had to be talked off a bridge in a suicide bid by manager Gil Hodges) but sober up by 1968. He’d be only the first of a few Angels having to go there.

Grba was a competitor to a fault, his signature moment sometimes thought to be the day he pitched in Yankee Stadium for the first time as an Angel, surrendered home runs in consecutive at-bats to Hall of Famer Mickey Mantle, and circled the mound screaming insults at Mantle as the latter rounded the bases.

But like Duren and Belinsky, Grba developed too much taste for alcohol. He admitted it began affecting his pitching as soon as 1963. Unlike Belinsky, who’d revive his career a few times in Hawaii, Grba became a minor league traveler until his drinking got far enough out of hand to force him out of baseball. “My priorities,” Grba would remember, “were all gone. [Hall of Fame pitcher] Bob Lemon saw me one day and said, ‘I’ve never seen a pitcher lose his stuff as fast as you did’.”

Grba lost his stuff and, in due course, three marriages, before he hit rock bottom in 1981, after several equally failed rehab attempts. This time Grba lived and worked at an El Monte, California detox center, after more than a decade bounding between jobs and between southern California and his native Chicago. Sneaking back to his room in the wee small hours one night, he lost his balance and—depending upon which account you believe—he hit the floor or fell through a window. Whichever it was, Grba finally quit drinking.

He got help from an unlikely source, according to Los Angeles magazine: Bo Belinsky. The rakish lefthander was once the toast of baseball thanks to patronage from fading but still influential columnist Walter Winchell after his no-hitter and five-game career-opening winning streak. But the Angels suspended him in August 1964, despite what looked a solid season in the making, after a hotel room brawl with veteran sportswriter Braven Dyer.

Belinsky’s career careened off the rails after his trade to the Phillies near the end of 1964 and ended after too much back-and-forth to the minors in 1970. Already a heavy drinker, Belinsky also became amphetamine addict while he was at it, the latter something he’d admit years later that he picked up in the Phillies’ bullpen. “I’d occasionally used greenies, amphetamines, as a starter, but in Philadelphia they had red juice,” Belinsky would remember, “and when I got into the bullpen, I started getting loaded every day, because as a reliever, you never know when you might have to play. This chemical started coming into my life. I thought I could handle it, because I was strong and still had that phony smile. But something was happening to my system.”

When Belinsky’s second marriage collapsed in 1981, he began his own battle to get and stay sober, including membership in Alcoholics Anonymous. In line with A.A.’s twelfth-step principle, carrying its message to fellow alcoholics, Belinsky reached out to Grba after learning of his former teammate’s struggle. “Bo and I had never been that close,” Grba told Los Angeles. “He was too Hollywood. But he came and got me and took me to an AA meeting. I was nervous, but Bo said, ‘Don’t worry, Eli, they’re all drunks just like you and me’.”

Grba stayed sober the rest of his life. So did Belinsky, after a few ups and downs in the 1980s including a suicide attempt of his own, before staying clean and working first as a Hawaii alcohol counselor and, later, a public relations executive for a Las Vegas automotive concern, before his death at 64 of complications from bladder cancer in 2001. So did Duren, who became an addiction counselor after his 1968 cleanup, working for various agencies and groups until his death at 81 in 2011.

Getting and staying sober brought Grba back to baseball. He became a minor league pitching coach and manager, a pitching coach again, and a scout, including in the Phillies’ system thanks to being clean and sober still when he re-connected with another Angels teammate, Lee Thomas, then the Phillies’ general manager.

Grba retired in 1997 and moved with his fourth wife, Regina, to Alabama. He also re-connected with his children, including son Nicholas, now a retired Air Force staff sergeant; and, Stacy, his daughter who also served with the Air Force. In 2016, Grba co-wrote his memoir, Baseball’s Fallen Angel. “The way I was drinking it is amazing I can remember anything,” he told an interviewer while promoting the book. “I had six alcoholic seizures and six DUIs. How I never killed myself I’ll never know.”

When the Angels celebrated their fiftieth anniversary as a major league franchise in 2011, Grba was invited to the ceremonies and to throw out a ceremonial first pitch. That day opens Grba’s memoir, co-written with Douglas Williams, a harrowing account of a haunted man who’d sent himself to hell and back.

“At that game Eli realized so many of his former teammates are no longer with us and I know he wondered why God left him here after he had lived so hard with his alcohol problem,” Williams said later. “Then he realized that maybe he was still here so he could tell his story and warn others of the pitfalls he fell into.”

“What I think about sometimes is about how I messed it up,” Grba told the Orange County Register of his self-shattered career and his three broken marriages. “Baseball has been a secondary thought to me ever since I got sober, I didn’t leave the Angels the way I wanted. It’s nice to be recognized as the first, nice to be remembered, and it’s an honor.”

Grba threw a perfect strike for that ceremonial first pitch. It was nothing compared to the perfect strike he threw for himself, his children, and his grandchildren, after he sobered up to stay.

You’d think that with all the whining about things like defensive shifts (which

You’d think that with all the whining about things like defensive shifts (which