From being part of a Cleveland team that shaved off a fifteen-game White Sox lead in the AL Central . . . to managing the Sox the rest of this season about which “disaster” might be flattery.

Once upon a time, when life was fair enough and the American League Central seemed a likely White Sox possession, Grady Sizemore and his 2005 Indians managed to turn a fifteen-game White Sox division lead in July to a mere game and a half entering the regular season’s final weekend. Even while they lost six of seven to the Sox along the way.

Those Indians forced the White Sox to think about and execute sweeping those Indians over that closing weekend to start those White Sox on the march to the World Series—which they hadn’t won since the Petrified Forest was declared a national monument. Sizemore finished the season leading the Indians with his 6.6 wins above replacement-level player.

That was then; this is now. Now, Sizemore—who took time after his playing career ended to make himself a husband and father, then worked as a $15-per-hour player development for the Diamondbacks at the behest of his friend Josh Barfield, whose move to the White Sox brought him aboard as a coach last winter—takes interim command of the White Sox for the rest of this year. God and His Hall of Fame servant Bob Feller help him.

There’s no way Sizemore could have played that final 2005 weekend against the White Sox and imagined the day coming hence when he’d have the White Sox’s bridge, even on an interim basis the team insists will remain just that while they look toward hunting a permanent skipper over the offseason to come. Neither could his legion of adoring Cleveland fans imagine it.

That 2005 opened a run of four straight seasons during which Sizemore became one of the American League’s top center fielders (37 defensive runs above his league average; .572 Real Batting Average*; 107 home runs; 128 OPS+) and matinee idols. The performance papers made him a superstar; his wiry physique and boyishly handsome face (not to mention what some have called his porn star-like surname) made him a sex symbol.

But the most irrevocable unwritten rule of Cleveland baseball for so long has been that no good deed goes unpunished. Not even the one that made Sizemore an Indian in the first place.

He came to Cleveland in the package the Indians all but embezzled out of the ancient Montreal Expos (it included pitching star to be Cliff Lee and second baseman Brandon Phillips) in exchange for pitcher Bartolo Colon. That’d teach them, and Sizemore, perhaps in that order.

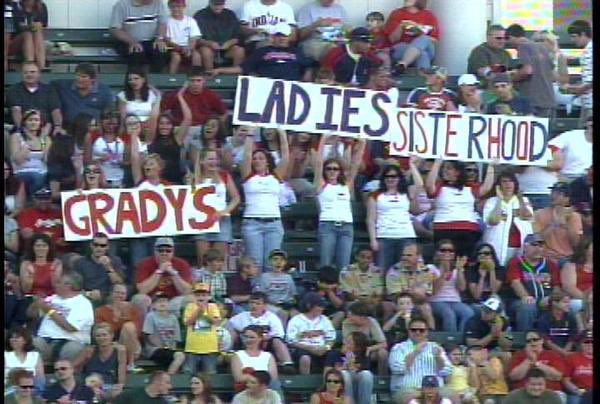

Around Cleveland, they didn’t name candy bars after Sizemore, but countless young women including a formal fan club known as Grady’s Ladies wore marriage proposals aimed his way on T-shirts in the Indians’ home playpen. (“I’m not trying to be the sex symbol of Cleveland,” he once told a writer who purred in print about his politeness and his modesty.) He managed to keep his marble (singular) and play ball; perhaps his worst known vice was driving a well-maintained baby blue 1966 Lincoln Continental.

“Good luck getting him to talk about himself,” said Indians relief pitcher Roberto Hernandez to Sports Illustrated‘s Tom Verducci. “He’s such a quiet guy who’s only interested in playing baseball and doing what he can for the team.” What he did was become one of the game’s respected and feared leadoff men, with power-speed numbers to burn, a kind of Mookie Betts prototype, but he might have done it too hard for his body’s taste.

This is how popular Sizemore was in his early Cleveland years. And that’s without showing the young ladies wearing T-shirts with marriage proposals for him.

That being Cleveland, and those being the Indians, Sizemore couldn’t be allowed to turn a promising first five years into a Hall of Fame career. He was battered, beaten, and bludgeoned by injuries that shortened three seasons following 2008 before leaving him unable to play at all for two to follow. He didn’t have Mike Trout’s statistics but he didn’t need those to become the Trout of the Aughts. He ended up playing in Boston, Philadelphia, and Tampa Bay without a fragment of his Cleveland best left to offer.

“Just coming back from one surgery is hard,” Sizemore told a reporter when he signed with the Red Sox. “When you lump seven in a short period of time, it kind of puts your body through the wringer a little bit. I kind of had to take a step back the last year or two, and kind of just get the body right and try to get healthy and not rush things.”

Sizemore had had a double and a bomb during a fourteen-run single-inning massacre of the Yankees in April 2009. At that season’s end, he’d undergo surgeries on his groin and his elbow. Followed by another abdominal surgery, back surgery, and three knee surgeries. The three-time All-Star and two-time Gold Glove winner was reduced from a Hall of Famer in the making to an orthopedic experiment who’d be lucky to average 72 games a year over his final four major league seasons, sandwiching two full seasons his body forced him to miss.

The good news is, Sizemore is in splendid health today, and nobody’s in a hurry to see him turn the team around from joke to juggernaut. They believe in many things in Chicago, but magic acts aren’t among them. Not even if it might have taken one to end the Sox’s horrific 21-game losing streak Tuesday night or save Pedro Grifol’s job on the bridge. The skinny had it that Grifol would survive only long enough to see that streak end, if it ended.

Grifol survived to watch his charges beat the Athletics, 5-1, but the following day the White Sox couldn’t keep a 2-0 lead past the seventh, then couldn’t overcome a freshly minted one-run deficit in the final two innings. Those attentive to whispers that Grifol didn’t preside over the most communicative or tension-free clubhouse (his total record with the Sox: 89-190 over two seasons) probably noted Sox general manager Chris Getz making a point of mentioning Sizemore’s apparent knack for drawing people closer to him (unlike the guy he’s going to end up spelling when we execute him!) when announcing Sizemore’s original addition to the coaching staff.

Sizemore, young and an Indian, wearing his love for the game unapolgetically while playing like a future Hall of Famer—before the injuries made him the Mike Trout of the Aughts.

“He’s got a strong understanding of the game, how to play the game,” Getz said of him when announcing his mission for the rest of this lost and buried season. “He’s very authentic and honest with his communication ability. And so we felt that Grady would be the right fit for getting us to the end of September and building this environment that’s more effective for our players. Grady is a very strong, steady voice that we look forward to having as the manager to finish up this season.”

A guy with baseball brains to spare who can endure seven surgeries in five years without looking for the nearest escape hatch to the nearest booby hatch is a guy who can handle getting these White Sox through a remaining season in which they’d kinda sorta like not to end up breaking the 1962 Mets’ modern record (40-120) for season-long futility.

The interim manager might even have a chance to so what some have thought impossible thus far this year. Those Original Mets sucked . . . with style. And laughs. Sizemore might not make these White Sox more stylish in self-immolation, but he might actually get them to laugh—even to prevent them from thoughts of sticking their heads into the nearest ovens.

The White Sox would have to win thirteen more games to elude liberating those 1962 Mets from the top of the bottomcrawling heap. If Sizemore can get that much out of them from this day forward, he might make other teams cast an eye upon him as a manager without an interim tag attached. He might even make the South Side believe in magic, after all.