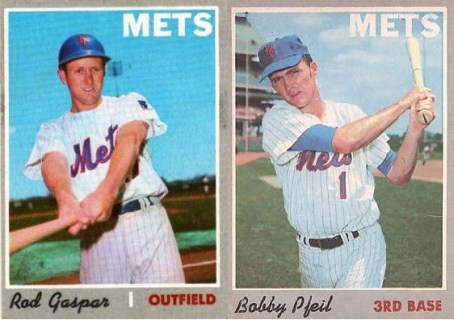

Rod Gaspar and Bobby Pfeil, as shown on their 1970 baseball cards. Proud to be ’69 Mets, they’re determined to see redress for pre-1980 short-career major league players frozen out of baseball pensions.

When new Mets owner Steve Cohen met the press Tuesday afternoon, he spoke of making the Mets meaningful again, and not just for another isolated period. “I’m not in this for the short-term fix,” he insisted in his low-enough-keyed manner. “I’m not in this to be mediocre.”

As he spoke of commitments to excellence, and emphasised people making the difference from the field to the front office, a reporter asked Cohen—like me, a Met fan since the day they were born—to name his outstanding Mets memories. God knew I had a warehouse worth of them myself, so this should have proven interesting.

It did. And how. The first such memory Cohen named named was left fielder Cleon Jones, two hands upraised, waiting for and hauling down future Mets manager Davey Johnson’s 1969 World Series-ending fly out, bringing his hands between his legs as he kneeled to finish what God as played by George Burns (in 1977’s Oh, God!) would call His last miracle.

Funny that Cohen should mention that first. This week I had the pleasure of speaking with two 1969 Mets: Rod Gaspar, the fourth outfielder, and reserve infielder Bobby Pfeil. Both still cherish their days as ’69 Mets. Both also care passionately about another baseball cause.

Gaspar and Pfeil want to see redress for short-career major league players such as themselves who were frozen entirely out of a major pension plan realignment in 1980 itself. The new plan changed pension vesting to 43 days major league service and health care vesting to a single day’s major league time. But the change excluded players with short careers who played between 1949 and 1980.

Both men live in California today. Neither are financially distressed themselves. They’ve both been successful in their post baseball lives, Gaspar in the financial services business, Pfeil as a builder/co-administrator of apartment complexes in California and other states.

Both are delighted to talk of their 1969 Mets and of the game in general. Get these two friendly, accommodating men talking about the pension freeze-out for short-career major leaguers, and they become just as passionate as they were as reserves always at the ready for the 1969 Mets and the manager they still admire, Gil Hodges.

The pension re-alignment affected over 1,100 short-career players originally. Life’s attrition has long since reduced the surviving number to 619. The ranks diminished to that number Sunday when Ray Daviault—a righthanded pitcher whose only major league time after nine seasons in the minors was 36 games as an original, 1962 Met—died at 86 in a pool accident at his Quebec home.

“They have no guts at all when it comes to running my particular game, baseball,” Gaspar says of the owners and players who agreed on the 1980 pension change and those today who bypass or ignore it. “I love baseball. I don’t like what they’ve done with the pension, eliminating guys who didn’t have the four full years, there’s a lot of guys out there who are hurting.”

In 2011, then-commissioner Bud Selig and then-Major League Baseball Players Association director Michael Weiner developed a small redress. They agreed the pre-1980 short-career players would get $625 a quarter for every 43 days major league service time, up to four years. Though it was a beginning, it didn’t allow the players to pass those monies on to their families upon their deaths, and those players were still not allowed into the players’ health plans.

Marvin Miller is known to have regretted not revisiting the pension re-alignment before he retired as the union’s director. Several of the frozen-out pre-1980 players have suggested the freeze-out tied to a perception that enough of the players in question were September call-ups who didn’t always make their major league teams out of spring training.

“I don’t think we’re important enough to pay attention to,” Pfeil says of the game’s attitude toward those short-career players. “We didn’t really have a unity, or a group, that was pursuing any changes. It kind of went away with nobody [pursuing] the reform of it.”

It may have taken until journalist Douglas J. Gladstone first wrote A Bitter Cup of Coffee, in 2010, before the freeze-out registered to even small degrees with people outside baseball. (Gladstone published an updated edition in early 2019.) Gladstone and others including New York Daily News columnist Bill Madden have written since about both the union’s and the Major League Baseball Players’ Alumni Association’s post-Wiener lack of interest in addressing any degree of the freeze-out.

“[T]hey . . . didn’t hesitate one bit taking my dues when I was a major league player,” former pitcher David Clyde told me of the union’s lack of response last year. “But as soon as you’re no longer a major league player, they basically don’t want to have anything to do with you.”

Pfeil says he once contacted the Alumni Association’s then-leader, former Expos pitcher Steve Rogers (who is still on the group’s board), leaving a voice mail to which he got no answer. That lack of response, too, is not atypical among their fellow freeze-outs.

“I’m not real happy that they left out players who actually played in the big leagues,” says Gaspar, who made the 1969 Mets out of spring training and ultimately scored the winning run in the tenth in Game Four of the 1969 World Series. “But think about it. They have so much money, the owners, the players’ union, they have so much money, how much money would it cost them to give the guys who are still alive the pension?”

Gaspar answered his own question quickly. He says that if a combination of the owners and the players’ union wanted to offer even the minimum $10,000 a year pension to the still-living, pre-1980 short career players, it might cost a little over six million dollars a year. “What is that to baseball?” he says. “A drop in the bag, probably.”

“All we hear about is the money that’s in the game,” Pfeil says, “and I think we’ve been a forgotten group that helped them get to where they attained this.”

Both former Mets think the issue might have gotten further redress if Weiner—who died of brain cancer in 2013—had lived instead. Why wouldn’t Tony Clark, the former first baseman who succeeded Weiner and is the first player to serve as the union’s director, take more interest in aiding former players whose major league careers didn’t endure?

“I think he’s working on things that he thinks are more important,” Pfeil says, “and we’re easy to forget about.”

“You think the players union cares about these retired ballplayers? You think the owners care? No, they don’t care,” Gaspar says. “I’m probably better off than most, and I feel badly for these guys. I know a number of them. I’ve been back to reunions and stuff, most of them have done fine . . . if it changes, to me that’d be wonderful for the guys who are still alive. I don’t see it happening because it’s a non-issue for the baseball players union and the owners.”

Gaspar and Pfeil are no strangers to collaboration. On 30 August 1969, they collaborated on one of the season’s strangest double plays in San Francisco’s Candlestick Park. With the Mets’ defense shading Hall of Famer Willie McCovey to pull to the right side, McCovey hit a long double to left in the bottom of the ninth.

Gaspar had to run from his positioning to try flagging it down, settling for extracting the ball when it landed and somehow became stuck in deep left. He dislodged the ball, wheeled, and threw home. “I threw it blind,” he still insists of the Hail Mary-like throw.

Blind or not, the throw hit Mets catcher Jerry Grote in textbook style to bag Giants right fielder Bob Burda with what would have been the winning run. But the usually heads-up Grote suffered a momentary brain fart: he thought Burda was the third out and rolled the ball back to the mound. An alert Mets first baseman Donn Clendenon charged, pounced on the ball, and whipped a throw to Pfeil at third to bag McCovey trying to advance on the mishap.

“I was playing like left center field, [center fielder Tommie] Agee’s over in right center, [right fielder Ron] Swoboda’s down the right field line,” Gaspar says. “McCovey’s a dead pull hitter. But he hit it about 300 feet down the left field line. It was about, I don’t know, two, three, or four feet fair. As soon as he hit it, I took off, because I knew [Burda] was going to try to score. And I got to the ball, right in front of the warning track, I think down the line it was 330 . . . I just pivoted and threw from that point. That was probably the best play I ever made.”

The 7-2-3-5 double play sent the game to the tenth inning, where Clendenon—with two out and, ironically enough, Gaspar and Pfeil batting on either side of him in the lineup—tore what proved a game-winning solo home run out of Hall of Famer Gaylord Perry.

Both Gaspar and Pfeil say they’re impressed with the way Cohen has put himself forth soliciting fan input and declaring his commitment to turning the Mets around for the longer haul. Is it possible, then, to get Cohen himself to think about the pension issue and seek a way to make things right at least for still-living, short-career, pre-1980 Mets players? Could Cohen, acting himself or soliciting help for those players from the team he’s rooted for since its birth, start a team-by-team snowball toward that redress.

“I think he sounds like a person that would be willing to do something like that,” says Pfeil, mindful that, if he could or does, it wouldn’t happen overnight. “I think he’s got bigger fish to fry for a couple of years, he’s got a few other issues to get in place in the next six months.”

Perhaps Cohen’s equally philanthropic and enthusiastic wife, Alex, whom he’s designated to administer the Mets’ foundation for community and charitable outreach, might be receptive to entreaties on behalf of just such pre-1980 Mets as Gaspar and Pfeil.

Both players cherish their memories as 1969 Mets and the friendships that remain among various members of the team, but they hope for the pension mistake to be redressed. “I believe in miracles,” Gaspar says. “I’m a Miracle Met. But some things just don’t get to happen and I believe this is one of those things. But I wish I was wrong, I really do.”

So do 617 more former players asking only that the game they love forget no longer that they, too, played the game in more ways than one.

Thank you for bringing attention to an issue that has affected our lives. I’m one of the players with 3+ years in the majors – and took part in the lock-out of ’76 which likely cost me additional time. Doug Gladstone has done a lot to keep this issue in front of anyone willing to listen. Thanks for being one of them.

Tom Johnson, MN Twins 74-78. And “yes,” I played against the Yankees in Shea Stadium during the renovation in 75.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Tom—Doug is a good guy; we’ve become friends over the past two years. It was his book and interest that made me aware of the pension issue and put me in touch with the former players I’ve spoken to about it. The bad news, aside from the obvious, is how nearly non-existent the issue seems to be in the sports media otherwise. I’m glad to do whatever I can do to help.

LikeLike