No, Jones didn’t loaf on that ball. And Hodges didn’t demur when Jones told him the reason it looked that way.

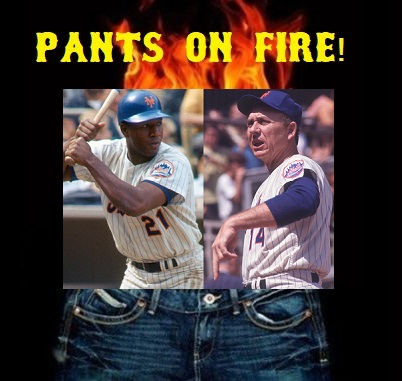

Everybody knows Gil Hodges pulled the Mets’ All-Star left fielder Cleon Jones right out of left field in the middle of an inning because Jones loafed on a double by Astros catcher Johnny Edwards. Everybody’s wrong.

The Mets skipper wanted full alert and full hustle. There’s no disputing that. He wanted his men to stay away from self-defeating thinking and play. Hodges wasn’t Leo Durocher’s kind of human time bomb, but that didn’t mean he suffered fools gladly, either.

But what you think you remember about that play, during the second game of a 30 July 1969 doubleheader in Shea Stadium, isn’t quite what went on.

The twin bill itself was a disaster for the Mets, losing both games, 16-3 and 11-5. “They were stealing on us, we were making errors in the field, we looked listless at the plate, [second game starting pitcher] Gary Gentry walked in a run and threw a wild pitch—it was just a real sloppy, lethargic effort on our part,” says Mets outfielder Art Shamsky. “We were a club in need of a wake-up call, and Gil was more than willing to oblige.”

In the top of the third Edwards flared one down the left field line off Hall of Famer Nolan Ryan in relief of Gentry. Jones on a bad ankle ran after it “tentatively,” says Shamsky, who played right field in that game, leaving Edwards on second with a double. Hodges left the dugout at once. In one of the most famous scenes in Mets history, the manager crossed the first base line without his usual skip step over it, which alarmed Shamsky at once.

Shamsky thought Hodges meant to make a pitching change—until he passed Ryan by. Then, Shamsky thought Hodges spotted something wrong with shortstop Bud Harrelson. “I said to Gil, ‘Me?” Harrelson would remember. Hodges replied, “The other guy.” Hodges kept walking toward left field, with Harrelson walking with him about half the way out. And approached Jones, while unnerving Shamsky across the outfield

I said to myself, Oh, shit, Cleon’s in trouble, and thought Jones would be wise to just dash through the visitor’s bullpen gate in left field. That’s because I had a feeling there had to be something stern that the hard-nosed, no-nonsense ex-Marine wanted to say to Cleon. Or worse.

“It was,” says Mets pitcher Jerry Koosman, “a scary walk.”

Jones remembers Edwards hitting the ball right down the line with “no way” to stop him from a two-base hit. “I ran after the ball the best I could but it was soaking wet in the outfield,” he’d remember, referring to conditions after a couple of days of rain. “Plus, I had a bad ankle. So when Gil walked out there, I was as surprised as everybody else. I thought something happened behind me.”

As Jones remembers and Shamsky affirms, Hodges got right to the point and asked Jones what was wrong. “What do you mean?” Jones replied.

“I don’t like the way you went after that last ball,” Hodges said plainly.

“We talked about this in Montreal,” Jones said. “I have a bad ankle, and as long as I don’t hurt the team, I could continue to play. Besides, look down.”

Hodges did look down. “He could see that his feet were under water,” Jones remembers.

“I didn’t know it was that bad out here,” Hodges then said. “You probably need to come out of the ball game.” Jones assented and player and manager walked back to the dugout together.

The following day, Hodges talked to Jones one on one. Wayne Coffey, in They Said It Couldn’t Be Done, said Mets bullpen coach Joe Pignatano overheard Hodges begin with a raised voice, demanding, “Look in the mirror and tell me Cleon Jones is giving me one hundred percent!” Now, pay close attention to what the manager is quoted by Jones himself as saying:

I wouldn’t have embarrassed you out there, but I look at you as a leader on this ball club. So if I can show the club I can take you out, it sends a message to everyone. Everybody seemed comfortable with this ball club getting its tail kicked and I didn’t like it.

Hodges may well have been alarmed at Jones’s inability to gun it for the Edwards hit, but note all the phrasings carefully. The manager didn’t just walk out to left field and pull his player without a word. Hodges didn’t make his move until after Jones told him the ankle was bothering him on the soaked turf.

But is it unreasonable to ask whether Hodges spontaneously seized a moment to do two things at once—get his ailing left fielder out of a game on a dangerously wet outfield before he ran into further injury issues, while sending his club a message not to be comfortable with getting their tails kicked?

Hodges probably could have picked any other moment that day to send his players that message. Especially in that third inning. This is the game log from that inning, with Gentry starting the inning on the mound for the Mets:

Doug Rader—ground out to second base.

Edwards—base hit to left center field.

Larry Dierker (the Astros’ starting pitcher)—Gentry wild-pitches Edwards to second; strikeout.

Sandy Valdespino—Infield single, Edwards scores on a throwing error by Mets second baseman Ken Boswell.

Hall of Famer Joe Morgan—walks.

Jimmy (The Toy Cannon) Wynn—base hit to left center field, Valdespino scores, Morgan to third base.

Norm Miller—Wynn steals second before Miller draws a walk. Bases loaded.

Denis Menke—Draws a walk, Morgan scores, bases loaded.

Curt Blefary—three-run triple.

Rader—Base hit into center field, Blefary scores. Hodges lifts Gentry for Ryan.

Edwards—The fateful flare double; Ron Swoboda replaces Jones in left field.

Dierker—Two-run homer.

Valdespino—Flies out to Swoboda, side retired at last.

You could point to a couple of other instances in that inning during which Hodges also could have sent his Mets a message, possibly and in particular the Ken Boswell error. But Boswell wasn’t anywhere close to the Mets’ leading hitter; Jones had a nicely swollen .360 batting average at the time, though Shamsky says he wished then (and still) that Jones had sat out the second game of the twin bill to give his bad ankle a rest.

“Gil did it to wake us up,” Jones said, careful to say “us” and not “me.” “That was his motive. If he could do it to someone hitting .360, he could do it to anyone. But everybody misinterpreted at the time what really happened between us.”

Including Hodges’ wife, famously enough. Shamsky says she once told him she called coach Rube Walker before her husband returned home and asked why Walker “let” Hodges make the move. “I really didn’t know where he was going,” Walker told the skipper’s lady. “Besides, Joan, I don’t think there’s anyone on this earth that could have stopped him.”

Mrs. Hodges had no intention of talking about Jones until Hodges insisted she get it off her chest. After initial resistance, she did: “I wouldn’t care if you got Cleon in the office after the game, shut the door, and wiped the floor with him. But whatever possessed you to do it on the field?”

“Do you want to know the gospel truth?” her husband replied. “I never realised it until I passed the pitcher’s mound. And I couldn’t turn back!”

It doesn’t look necessarily as though Hodges thought at once a lack of hustle was involved, especially since Jones reminded the manager about his bad ankle and the soggy ground and Hodges—who took a back seat to few when it came to resisting back talk—didn’t reject either reminder.

Gamesmanship wasn’t alien even to the Mets’ quiet, honest manager. Just ask Jones himself, who’d be the immediate beneficary in the World Series over a certain shoe polish scuff on a certain ball that hit him in the foot. But even Hodges wasn’t above a little gamesmanship by way of a wounded warrior, either.

Note the phrasing Shamsky quotes Jones as using retrospectively about Hodges and the soggy left field incident:

He was tough, but he was thorough. He was just the total package as a manager. If he went out there onto the field and felt like you didn’t have it, you were out of there. He just did everything right. We no longer beat ourselves. And when you don’t beat yourself, it’s harder for the other guy to beat you.

If Hodges knew Jones was ailing on a ball he might have reached faster on an unaffected wheel, who can blame him for seizing a moment to send his team a message about getting too comfortable with getting hammered?

But the deeper you look into the story, through the courtesy of those who were there, the less it looks as though Hodges just poured out of the Mets dugout intent on dragging Jones off the field, by his ear or otherwise. Seeing Jones ailing gave him the opening for a perfect two-fer: get his man off his bum wheel awhile and let his players know it wasn’t a picnic to invite the other guys to hand them their heads.

Shamsky tells the story in, After the Miracle: The Lasting Brotherhood of the ’69 Mets. About which a full review will be forthcoming.

Jones may have been humiliated or infuriated in the moment, but he told Jack Lang, a writer for the Long Island Press and The Sporting News, “If I didn’t respect what [Hodges] is trying to do, I could very easily hate his guts. But I don’t.”

“Hodges didn’t hold any grudges, either,” Coffey wrote in They Said It Couldn’t Be Done. “Jones sat for a couple of games, then got pinch hits in the next two games and was back in the lineup full time. When he was going for the batting title at the end of the year, Hodges batted him leadoff to help him get some extra at-bats.”

Hodges first told the Mets’ press box that Jones had a foot issue. His veteran third baseman Ed Charles, maybe more a spiritual than a baseball presence on the 1969 Mets, and was on the bench when Hodges made his surprise move, translated the manager’s intention this way:

He made it clear to all of us. If there is something wrong with you and you can’t give me one hundred percent, you let me know and I will put somebody else in the lineup. There’s nothing wrong with that. But when you hit that field, I want to see one hundred percent.

It made perfect sense for Hodges to sit Jones out a couple of games to follow to rest his ailing ankle further. Unlike his Cubs counterpart Durocher, who tended to ream his players as quitters if they complained about injuries, Hodges didn’t equate injury with indifference, even if he wanted to send Jones and his other players a message about honest effort.

In no reputable translation of the incident then or now does anyone suggest Hodges took an I-don’t-want-to-hear-it stance when Jones told him on the spot his ankle continued to bother him.