They once said, “There’ll sooner be night games at Wrigley than the DH in the NL,” didn’t they? Well, now . . .

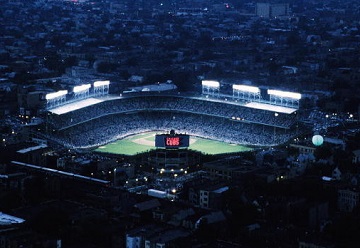

There was a time you would think the world would implode if the National League adopted the designated hitter, as the American League did in 1973 and as the Major League Baseball Players Association wants the National League to do soon. And some people still believe it. Well, there was also a time (and a rather noisy contingency arguing either way) when you would have thought the world would implode if the lights finally went on at Wrigley Field, which they did on 8 August 1988.

You still may find Cub fans who think that was a date equal in infamy only to the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre, the Chicago Fire, or the 1968 Democratic National Convention riots. The only thing in Chicago infamous about the night the lights went on at Wrigley was the game between the Cubs and the Phillies being rained out before the fourth inning was finished.

Surely there were enough Cub traditionalists who believed the rains were God expressing His displeasure, as if decades of losing baseball with only the occasional rude interruption were worth the preservation of the great daytime at the Friendly Confines. All the rainout did was delay the inevitable. The following night, the lights went on at Wrigley Field again. And the Cubs beat the Mets, 6-4.

That and the world failing to implode on cue was the good news. The bad news was that the presidential campaign, the Preppie vs. Zorba the Clerk, continued apace. Little by little, from that day forward, Cub Country began assimilating the idea that some traditions weren’t worth keeping if they secured other distasteful traditions—like losing baseball. They finally won their first World Series since the Roosevelt Administration (Theodore’s) at night, too.

“Lovely, just lovely. The park is lovelier than my team,” Mets manager Casey Stengel said when he saw Shea Stadium for the first time. Cub fans finally figured out that their ballpark was lovelier than their team even under the lights. And maybe National League traditionalists are figuring out that the designated hitter isn’t the spawn of Satan, after all.

Sure it’s fun when Madison Bumgarner hits those home runs every couple of blue moons, the way he did twice on Opening Day once. But as NBC Sports’s Craig Calcaterra reminds us, Bumgarner’s lifetime slash line as a hitter is .183/.228/.313, with a 54 OPS+. If you think the Giants pay Bumgarner for the seventeen home runs he’s hit in ten major league seasons, hurry up before you miss the Orioles moving back to St. Louis.

Oho, but the NL’s lack of a DH “adds value to guys like Bumgarner and Kershaw and Scherzer who are good at all of baseball, not just part of it,” says one tweeting responder to Calcaterra’s reminder. “And it also adds strategy to the late innings.”

If Bumgarner’s batting slash line indicates he’s good at “all” of baseball, then I’ve been learning about law enforcement from Bonnie and Clyde. Clayton Kershaw’s batting slash is .163/.209/.188 with a 14 OPS+. Max Scherzer’s lifetime slash is .194/.227/.220 with a 22 OPS+. All you have so far is Bumgarner out-slugging two fellow pitchers, as well as batting lines like that indicating that none of the three is good at all of baseball. And they’re only being paid to be good at one thing which is a full-time job.

The late-inning strategic argument now makes as much sense as trying to put out a factory fire with water pistols. For longer than you might care to think, managers haven’t been lifting as many pitchers as once upon a time for pinch hitters; assuming their incumbents and their defenses are getting the jobs done otherwise, the managers have been going to the bullpens to begin late innings, and they’re going to pinch hitters for other than pitchers (depending on the depth of their position playing roster) more often.

Incidentally, pitchers overall in 2018 batted .115. Those who think bringing the DH to the National League would reduce it to the “kiddie league” they think the American League is with it should ponder Thomas Boswell: “It’s fun to see Max Scherzer slap a single to right field and run it out like he thinks he’s Ty Cobb. But I’ll sacrifice that pleasure to get rid of the thousands of rallies I’ve seen killed when an inning ends with one pitcher working around a competent No. 8 hitter so he can then strike out the other pitcher. When you get in a jam in the AL, you must pitch your way out of it, not ‘pitch around’ your way out of it.”

Did you know that the first three World Series after the American League adopted the DH were played without it? It didn’t show up in the Series until 1976, when baseball decided all Series games would feature a DH. The Mustache Gang Athletics won the 1973 and 1974 Series (and the ’73 Series was closer than even its seven-game length suggests: the A’s scored only three runs more than the Mets); the Reds beat the Red Sox in the 1975 thriller.

Then came the 1976 Series with Dan Driessen, the Reds’ first baseman, as the National League’s first-ever designated hitter. He did that job for all four games of the Big Red Machine’s sweep of the revived Yankees. (He did it well enough to post a 1.152 OPS for the Series—second only to Series MVP and Hall of Famer Johnny Bench.) The Series featured the DH for all until 1986, when it was applied strictly in the American League park. Red Sox pitcher Bruce Hurst looked so inept trying to bat in Game One of that Series (in Shea Stadium, and Hurst struck out in all three plate appearances) that even the umpires fought not to laugh too hard.

Another question is why on earth would you care to risk a pitcher being injured while swinging a bat or running the bases? Stop laughing and remember Adam Wainwright. In his seventh game of 2015, in late April, Wainwright popped his Achilles tendon . . . while batting. He lost the rest of that season, the Cardinals lost the division series to the Cubs, and he’s never been the same pitcher since that he was before the injury.

Stop laughing and remember Chien-Ming Wang. He looked like a Yankee mainstay in the making, until a 2008 interleague game against the Astros, before the Astros were moved to the American League. Wang reached base as a batter and was rounding for home on a subsequent play when he tore the lisfranc ligament in his right foot.

He missed the rest of the season and never again looked like the pitcher who was the fastest Yankee to reach fifty pitching wins since Ron Guidry. His injury-pockmarked-from-there career ended in 2016, after three more major league teams tried to revive him and failed. But boy wasn’t it fun to see one of those American League pitchers have to run the bases and play real baseball!

(Don’t even think about uttering “Shohei Ohtani.” The Angels never let him bat on the days he pitched last year, and they never let him pitch on the days they plugged him into the lineup as the DH. Ohtani is an outlier, albeit an extremely talented one who earned his Rookie of the Year award.)

Sandy Koufax’s Hall of Fame career was shortened by elbow arthritis when he was, well, not at his peak but about ten dimensions beyond it. Do you remember how that arthritis made itself manifest after who knew how long it merely festered in gestation? It started in August 1964—on the bases. On a pickoff attempt. (I looked it up for you: Koufax only once ever tried to steal a base and was caught red handed, and probably red faced.)

If you remember how futile Koufax was with a bat in his hands overall, you’d think the idea of him on base at all, never mind trying to pick him off, was tantamount to sending Willie Mays out to pitch a no-hitter. When Koufax scrambled back (he was safe), he made a perfect four point landing on his elbows and knees, jamming his left elbow a little. Two starts and wins later, he awoke to a pitching elbow the size of his knee. Career days numbered, even if nobody realised it in the moment.

Koufax, Wainwright, and Wang are just three examples. You can also remember Randy Johnson’s career finish—four mere relief appearances in 2009 with the Giants. Until he made those, Johnson spent about a third of that season on the disabled list with a torn rotator cuff—incurred while he was batting. Was that the way you wanted to see a great pitcher mosey off into the proverbial sunset of a Hall of Fame career?

Sure, we all had a blast when Bartolo Colon, then a Met, bombed James Shields into the left field seats in 2016, in San Diego, for Colon’s first major league home run. It was a laugh and a half of pleasure watching Colon run the bases like a cement truck with a flat inner rear tire, and watching the Mets empty the dugout before he arrived after touching the plate.

It was such a blast we almost forgot Colon was 43 years old, in his nineteenth major league season, in only his 226th lifetime at-bat since he spent the big bulk of his career in the American League. His lifetime slash: .084/.092/.107, and an OPS+ of minus-45. And I didn’t notice the Mets in any big hurry to have him grab a bat and starting loosening up to pinch hit in the wild card game they lost that year.

You’ve probably heard it said often enough that American League teams with the DH can put what amounts to an extra leadoff hitter into the number nine batting lineup slot. Why would it be so terrible for National League teams to do that? Especially since sliding in an extra leadoff hitter might move the line appropriately enough for them to slide an extra potential run producer into the number two slot?

America is a country that has had growing pains enough in its comparatively young life that several traditions have died to no regret. Some died very hard, though die they must. (We fought a civil war over one of them.) Some died over longer and more cumulatively painful times, though die they must. Enough of them absolutely had to die and we are by and large better for that. The question to ask of tradition is not whether tradition qua tradition is to be preferred, it’s whether there are those traditions that are hazardous to a nation’s core principles or a game’s health.

Baseball’s had some growing pains, too. There was once a time when the nation and some of the game’s leading figures thought the home run would destroy the game. Ty Cobb and John McGraw objected to its impediment (so they alleged) to “scientific baseball.” (Which didn’t stop McGraw from nurturing and turning Hall of Famer Mel Ott loose when that National League home run king came under his wing and of age.) Ring Lardner once said the advent of the live ball and the home run ruined baseball for him far more than the Black Sox scandal could.

There was once a time when baseball feared such things as broadcasting, night ball (and remember, again, how long the Cubs held out against it), and shifting franchise locations would be the end of the game as we know it.

They thought free agency would make the game competitively imbalanced, too. As if the game was in perfect competitive balance when the Yankees won all those 20th Century reserve-era pennants and there were only two exceptions to New York World Series winners (the 1957 Braves, the 1959 Dodgers) during the 1950s.

The National League has held out against the DH about as long as the Cubs once held out against night ball. (The Cubs actually started planning night ball before Pearl Harbour and the world war to come compelled then-owner Phil Wrigley to send the planned lights and support structure materials away on behalf of the war effort.) And like the Cubs and their faithful regarding the lights, the DH in the National League won’t inflict curved spines, hairy hands, or erectile dysfunction.

Baseball suffers more profound compromisings. Things like tanking teams. Things like hitters obsessed with launch angles. Things like hitters and coaches un-obsessed with busting the shifts by thinking about hitting into the wide-open spaces even (especially?) when there’s a no-hitter in the making against them. (You’re fool enough to leave that wide open a space for me when your guy’s pitching a no-hitter, you’ve bought your own busted no-no.) Things like the so-called “unwritten rules” to which too many players keep clinging. (I say again: you want to play baseball like businessmen, wear three piece suits on the field.)

The Opening Day Bumgarners and the Twilight Zone Colons are the extremely rare exceptions, not the rules. What would you prefer, really, the thrill that appears as frequently as Halley’s Comet; or, the thrills that come every day from men doing their proper jobs for nine innings or more, without risking losing one of them to injuries doing things they’re not being paid to do? (Speaking of thrills, I’m sure even die-hard National League fans weren’t immune to those provided by David Ortiz, to name one, for several postseason Red Sox conquerors.)

“We try every way we can think of to kill this game, but for some reason nothing nobody does never hurts it,” said Sparky Anderson, once upon a time. The sun will still rise, the moon will still shine, the flora will still bloom, the fauna will still roam, and life as we know it will go ever onward, even when the National League accepts reality and the designated hitter.

What I’ve never understood is how does DHing start so young now (high school) and pretty much until Triple A there are DHs. For these NL Pitchers there is almost no training in between those 10 or so years. So we have gotten to the point that we increase training and let pitchers hit or we adopt the DH in the NL and not worry about it ever again.

LikeLike